An appreciable slice of Now the Hell Will Start takes place in the Ledo Stockade, an United States Army prison in North-East India. The place was known for the casual brutality of its guards, several of whom had worked as chain-gang supervisors back in Uncle Sugar. The stockade’s abysmal conditions play a key role in the tragedy at Now the Hell Will Start‘s heart.

An appreciable slice of Now the Hell Will Start takes place in the Ledo Stockade, an United States Army prison in North-East India. The place was known for the casual brutality of its guards, several of whom had worked as chain-gang supervisors back in Uncle Sugar. The stockade’s abysmal conditions play a key role in the tragedy at Now the Hell Will Start‘s heart.

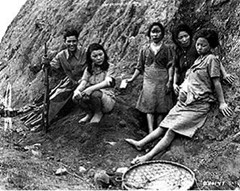

What’s left unsaid in the book is the Ledo Stockade’s role in the history of “comfort women”—Korean ladies used as indentured sex servants by the Imperial Japanese Army. Much of what we know about the day-to-day lives of these women comes from interrogations done at the stockade; the involuntary prostitutes had been captured during the Battle of Myitkyina. The Army’s Psychological Warfare Team reported its findings here; the interrogators seemed oddly unsympathetic to the women, despite all the hardships they’d been forced to endure:

The interrogations show the average Korean “comfort girl” to be about twenty-five years old, uneducated, childish, and selfish. She is not pretty either by Japanese of Caucasian standards. She is inclined to be egotistical and likes to talk about herself. Her attitude in front of strangers is quiet and demure, but she “knows the wiles of a woman.” She claims to dislike her “profession” and would rather not talk either about it or her family. Because of the kind treatment she received as a prisoner from American soldiers at Myitkyina and Ledo, she feels that they are more emotional than Japanese soldiers. She is afraid of Chinese and Indian troops.

The comfort-women issue continues to echo in contemporary relations between Japan and South Korea. Check out this fascinating piece from last year, which examines the Korean survivors’ ongoing efforts to wrangle a formal apology out of Japan—as well as a growing vogue for revisionist history among Japanese scholars.

Jordan // May 8, 2009 at 3:54 pm

The inability of governments to even extend apologies in cases where it is clear that their forebears made horrible mistakes, never ceases to amaze. From the Armenian Genocide to “comfort women” to the forced relocation of aborigines, acknowledgment of wrongdoing is curiously absent. To make the situation even more confusing, it’s rare that the people who would be making these apologies would need to claim personal responsibility. The blame is attached to those who are often long dead. Do governments really believe themselves to be so infallible that they can do nothing wrong? What is so tremendously difficult about saying “those who came before us really fucked things up?”.

Brendan I. Koerner // May 8, 2009 at 9:21 pm

@Jordan: You raise a point that I’ve long pondered, and I think it gets at the very heart of folks’ different perceptions of the world. Some people have so much identity wrapped up in their personal historical narrative; others view breaking free from that narrative as a worthy goal. That schism leads to two competing mindsets: One which regards apology as a weakness, another that calls it a strength.

Aubrey Maturin // May 9, 2009 at 7:45 am

In Lee Kuan Yew’s “The Singapore Story,” he writes about the Japanese takeover of Singapore from the British in WWII. Some observations from Lee on comfort women:

“Within two weeks of the surrender, I heard that the Japanese had put up wooden fencing around the town houses at Cairnhill Road… I heard from nearby residents that inside there were Japanese and Korean women who followed the army to service the soldiers before and after battle. It was an amazing sight, one or two hundred men queuing up, waiting their turn… I thought then that the Japanese army had a practical and realistic approach to such problems, totally different from that of the British army. I remember the prostitutes along Waterloo Street soliciting British soldiers stationed at Fort Canning. The Japanese high command recognized the sexual needs of the men and provided for them. As a consequence, rape was not frequent. In the first two weeks of the conquest, the people of Singapore had feared that the Japanese army would go on a wild spree. Although, rape did occur, it was mostly in the rural areas, and there was nothing like what had happened in Nanking in 1937. I thought these comfort houses were an explanation.”

Brendan I. Koerner // May 9, 2009 at 11:32 am

@Aubrey Maturin: Fascinating, thank you for the quote.

Indeed, it would seem most pragmatic for an army to address its soldiers’ carnal needs. As I wrote in NtHWS, “An army travels not only on its stomach, but also on its loins.”

I wonder if there is any data on VD rates among Japanese soldiers versus those of American and British troops.