We’ve previously written about Allied mustard-gas experimentation during World War II, involving live human subjects who were occasionally given no protection whatsoever. But it wasn’t until we read about the Bari disaster that we realized hundreds of Allied troops perished from mustard-gas exposure. This wasn’t due to deliberate release, mind you, but rather a horrific side effect of a German bombing raid. An Army history page tells the tale:

We’ve previously written about Allied mustard-gas experimentation during World War II, involving live human subjects who were occasionally given no protection whatsoever. But it wasn’t until we read about the Bari disaster that we realized hundreds of Allied troops perished from mustard-gas exposure. This wasn’t due to deliberate release, mind you, but rather a horrific side effect of a German bombing raid. An Army history page tells the tale:

During every campaign there was always the threat of the Germans using poison gas. By the end of 1943, the strategic initiative in the war had passed to the allies. The allies feared that Hitler could use poison gas to redress the strategic balance. While the United States condemned the use of poison gas, President Roosevelt pledged that the US would reply in kind if the Germans used poison gas first. In support of this pledge, the Liberty ship, John Harvey was selected to convey a shipment of mustard gas to Italy to be held in reserve.

The John Harvey was loaded with two thousand M41-A1 100 lb mustard bombs at the Baltimore cargo port. The John Harvey sailed for Norfolk on October 15, 1943 and then onto Oran, Algeria by convoy arriving on November 2, 1943. From Oran, it proceeded in convoy to Augusta, Sicily and then to Bari arriving at Bari on November 28, 1943…

The John Harvey was still waiting to unload on December 2, 1943. Since secrecy was paramount and few people knew of the mustard gas on board, the John Harvey was not given priority to unload its cargo of mustard bombs.

The German attack on Bari began at 7:20 in the evening on December 2, 1943. The planes flew in from the east. The docks were brilliantly lit and the East jetty was packed with ships. There was no time for the ships in the harbor to get underway.

Well over 600 soldiers lost their lives as a result. But Winston Churchill insisted that the incident be hushed up, even though such secrecy likely led to more post-incident deaths (since doctors weren’t aware of the blistering agent’s involvement). Churchill’s reasoning? “He believed that publicizing the fiasco would hand the Germans a propaganda victory.”

Of course, we can never read a mustard-gas account without thinking of Wilfred Owen’s haunting “Dulce et Decorum Est,” one of our favorite poems. Nothing has ever made us more grateful not to have been a trench dweller on the Western Front.

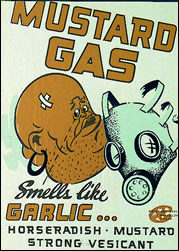

(Image via the National Museum of Health and Medicine)

Jordan // Jun 8, 2009 at 8:42 pm

Renouncing the use of chemical and biological weapons is one of the best decisions we’ve made as a planet. They are some of the dumbest ways to kill people ever conceived of by man.

Brendan I. Koerner // Jun 9, 2009 at 10:06 am

@Jordan: It’s interesting that the ban seems to have been relatively effective. Gas was obviously used in the Iran-Iraq War (and then by Saddam on the Kurds), but I can’t think of any other recent conflicts in which chemical weapons were a factor. That includes lots of nasty border wars where you’d think the temptation would be overwhelming. So this gives me hope for the future of all arms negotiations.