With the Chinese town of Ziketan locked down on account of pneumonic plague, it’s worth looking back at a similar incident from 15 years ago: the Surat plague of 1994. The Indian city ended up recording approximately 5,150 cases of pneumonic plague, which resulted in a shade under 60 fatalities—by no means a major epidemic, despite an initial shortage of antiobiotics. But in the early days of the outbreak, the widespres fear was the most difficult thing to control (PDF):

With the Chinese town of Ziketan locked down on account of pneumonic plague, it’s worth looking back at a similar incident from 15 years ago: the Surat plague of 1994. The Indian city ended up recording approximately 5,150 cases of pneumonic plague, which resulted in a shade under 60 fatalities—by no means a major epidemic, despite an initial shortage of antiobiotics. But in the early days of the outbreak, the widespres fear was the most difficult thing to control (PDF):

When news of the plague became known to the public, one-forth of Surat’s population (0.7 million) fled the city. The people who fled took all types of transport and paid whatever necessary. Transport operators made an enormous profit. The panic stricken people took taxis, tempos (three wheelers), trains and buses to flee the city. The panic was wide spread; every person with swollen lymphnodes was thought to have plague. The mass exodus occurred over long distances by railways and short distances by buses and other carriers. Surat does not have an airport for commercial flights. The train and bus stations were full of people struggling to make space for themselves and their family members, sitting, standing, hanging out the doors and windows and even on the roofs. The city of Surat consists of a large number of migrant workers who come not only from the state of Gujarat, but also from north-western and eastern India. Most of these migrants work in the silk and cotton textile mills, and diamond cutting and jewelry industries. Such migrants also come from the adjacent states of Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh. These migrants tried to leave the city in order to get back to their home towns and villages, thinking that there they would find safe havens. While doing so, some infected migrants in the incubation stage, carried the disease with them.

The residents of Gurat fled in part because the mere mention of the word “plague” carries such sinister connotations—never mind that the pneumonic version of the disease is eminently treatable, at least compared to its bubonic cousin. It’s also bears mentioning that the epidemic wasn’t even confirmed as plague until several years after the fact, when DNA analysis (PDF) finally detected the fingerprint of Y. pestis. But in the midst of a Black Death panic, no one wants to wait around for the eggheads to confirm their worst fears.

A nice little FAQ on pneumonic plague here. And a little history lesson on Renaissance Italy’s surprisingly smart anti-plague strategies here.

Joseph A. Parks,MD // Jan 26, 2012 at 2:58 pm

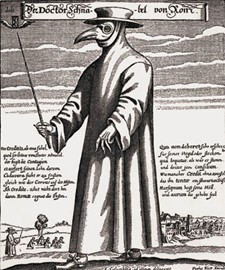

This picture of the plague physician has been extremely helpful for my paper on the plague.