Inspired in part by the “Meat is the new bread!” daring of the much maligned KFC Double Down, we recently found ourselves keen on learning more about the history of America’s love affair with flour. There is, of course, good reason that one of our most patriotic songs goes out of its way to shout out those “amber waves of grain”—namely, the fact that bread-y products have long been a centerpiece of our diet.

Inspired in part by the “Meat is the new bread!” daring of the much maligned KFC Double Down, we recently found ourselves keen on learning more about the history of America’s love affair with flour. There is, of course, good reason that one of our most patriotic songs goes out of its way to shout out those “amber waves of grain”—namely, the fact that bread-y products have long been a centerpiece of our diet.

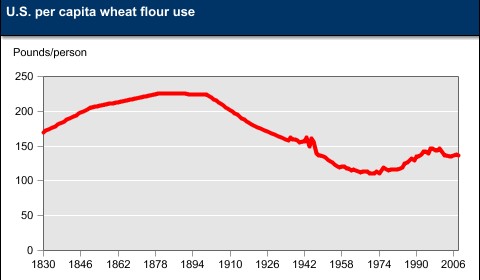

But as demonstrated above, our current grain consumption pales in comparison to that of our turn-of-the-century ancestors. And therein lies a rather fascinating tale about the way in which extremely clever marketing altered the American diet:

Historically, economic development has been accompanied by the substitution of meat for grain in the diet, and this was true in the United States starting in the 1870s. However, breakfast-food manufacturers promoted the opposite for breakfast. They convinced people to substitute highly processed grains for meat as healthy and convenient.

John Harvey Kellogg began experimenting with breakfast cereals in the 1870s, introducing a whole-wheat breakfast cereal in 1880 as a health-food product. This breakfast cereal was eventually named granola. Later, the Kellogg brothers created a wheat-flake breakfast cereal, called Granose, also as a health-food product. C.W. Post developed Postum in 1895 and then Grape-Nuts in 1898.

Cooked grain (porridge) was a common dish among the European immigrants in America in Colonial times. The Quaker Oats Company produced oatmeal, the first successful ready-to-cook cereal, in the 1870s. Later, Thomson Amidon discovered coarsely ground wheat could also be cooked into a breakfast cereal. Because of its color, he called it Cream of Wheat.

With new technologies, new products, and improved infrastructure—and the resulting lower costs—flour consumption rose during the 19th century. During the closing decades, consumption remained at very high levels as new and improved wheat products were introduced.

It took the advent of mass refrigeration to steer folks away from wheat-based foods, and toward the meat and dairy that have expanded our collective waistlines to a rather shocking degree. Noting the squiggles in the graph as the line moves toward modern times, however, we find ourselves wondering how closely wheat consumption tracks with economic cycles. Do we invariably eat more wheat as the needle swings toward fiscal gloom?

And beyond that, how does this chart compare to what’s taking place in the superpowers of tomorrow—specifically India and China. Perhaps we can tell a lot about a country’s development based on the ebb and flow of its grain consumption. Though, as the American experience reveals, the curve can be altered from its natural course by men of John Harvey Kellogg’s ilk.

Like gas stations in rural Texas after 10 pm, comments are closed.