Our post about Teddy Roosevelt’s health-care reform attracted a fair number of responses, in particular the ending snippet about the Progressive Party’s opposition to privately contracted prison labor. As one commenter pointed out, this opposition wasn’t borne out of genuine concern over the practice’s moral shortcomings, but rather Big Labor griping over the downward pressure on wages. After all, why would a company hire unionized workers if it could enlist the services of inmates who needn’t be paid (at least directly)?

Our post about Teddy Roosevelt’s health-care reform attracted a fair number of responses, in particular the ending snippet about the Progressive Party’s opposition to privately contracted prison labor. As one commenter pointed out, this opposition wasn’t borne out of genuine concern over the practice’s moral shortcomings, but rather Big Labor griping over the downward pressure on wages. After all, why would a company hire unionized workers if it could enlist the services of inmates who needn’t be paid (at least directly)?

As it turns out, Roosevelt took an interest (PDF) in this issue during his days in the New York governor’s mansion, too—he introduced legislation that would have “devised means whereby free mechanics should not be brought into competition with prison labor.” The bill may have died before passage, but its mere introduction certainly garnered Roosevelt some key labor backing for his subsequent presidential run.

Delving into this snippet of history has got us thinking about an underlying topic: how often has economic self-interest led to changes that we now view as morally just? In other words, what great movements of yore may have had their origins in mere pragmatism, but are now viewed as genuinely righteous?

The first one that popped to our minds was 19th-century abolitionism. Now don’t get us wrong—there were certainly abolitionists who motives were entirely lacking in self-interest, and who were genuinely revolted by the “peculiar institution.” (We’re looking at you, William Wilberforce.) But there’s a case to be made that much of the movement’s success is due to the support of businessmen who recognized slavery’s economic shortcomings. Such is the core thesis of Eric Williams’ Capitalism and Slavery, which argues that many English abolitionists were more keenly interested in propping up West Indian sugar prices than freeing their fellow man. And the Trinidadian writer C.L.R. James had a similarly skeptical take on abolitionist motives:

Those who see in abolition the gradually awakening conscience of mankind should spend a few minutes asking themselves why it is man’s conscience, which had slept peacefully for so many centuries, should awake just at the time that men began to see the unprofitableness of slavery as a means of production in the West Indian colonies.

Any other nominees for moral goods that have stemmed from economic or political self-interest, at least in part?

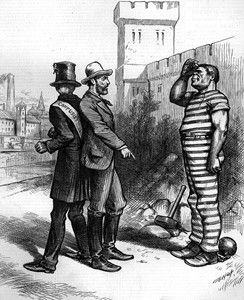

(Image via Georgia State University’s Southern Labor Archives)

Bobby // Sep 15, 2009 at 4:47 pm

Great subject, Brendan. I’ve only read snippets of it, but I think Dierdre McCloskey’s The Bourgeois Virtues takes on your question pretty directly.

And if you’re curious about the economic case against slavery, you really ought to check out Time and the Cross and the furor that followed it. Fogel made the case that slavery was profitable, and that the proper objection to the institution was a moral objection, not an economic one. (To say the least, not everyone agreed.)

My own general feeling is that–regardless of the merits of Fogel and Engerman’s specific argument–it’s dangerous to let the lines between economics and morality get too blurry. The dangers of letting that happen are plain in the current health-care

debacle–I mean, debate. What Obama presented as a moral case for universal health care during the campaign became an economic case this spring, which left him scrambling when the economics turned against him.Brendan I. Koerner // Sep 15, 2009 at 6:06 pm

@Bobby: Thanks for the great book recs.

I think the case made by James et. al. was that slavery was mainly profitable for the landed aristocracy, the political clout of which diminished with the advent of the Industrial Revolution and the rise of the bourgeoisie. But that alone probably isn’t sufficient to explain the abolitionist phenomenon—it’s one thing to frown on slavery, quite another to make its abolition a crusade. Could this be one of those “little from Column A, little from Column B” issues? That is, shifting economic realities made the new industrial class more receptive to the moral argument?

On health care, I always thought that the economic argument would be more effective at getting skeptics off the fence. If you don’t already see the moral case for reform, I don’t think any speeches will change your mind.