In the course of questioning the utility of suicide-proof barriers on bridges, a political scientist makes an intriguing observation:

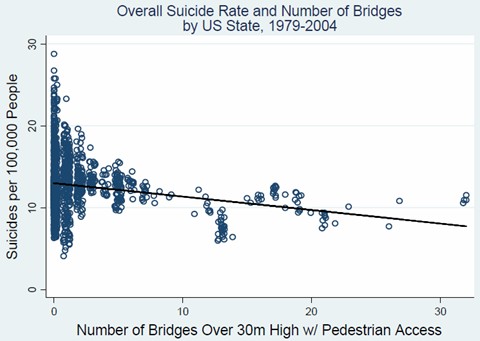

In order to determine if exposure to bridges increases the suicide rate, I examined the relationship between the suicide rate and the number of bridges likely to attract suicidal individuals in all 50 states plus Washington D.C. from 1979 through 2004 (the only years for which complete data was available). Bridges likely to attract suicide victims were defined as those bridges over 30 meters (about 98 feet) high with pedestrian access. In order to statistically test the relationship between the number of bridges and the suicide rate in a state in a given year, I use a technique known as linear regression. Essentially, this is the process of fitting a trend line to a scatter plot of data, and then testing to see if the trend line has a positive, zero, or negative slope. If increased exposure to bridges leads to more suicides, we would expect to see more suicides in states that have more bridges, and thus a positively sloping trend line.

This figure reveals that there is a negative relationship between the overall suicide rate and the number of bridges in a state, exactly the opposite of the relationship we would expect to see if bridges helped cause suicides and suicide prevention barriers saved lives. It does not seem plausible that increasing the number of bridges in a state would directly reduce the suicide rate – instead, the number of bridges in a state may be a proxy for some other factor that reduces the suicide rate (such as a robust state economy). At any rate, there is no evidence to suggest that increased exposure to bridges increases the suicide rate.

The author then makes a leap to contend that this means barriers have little effect, since people intent on suicide will simply find another way of bringing about their own demise. While we’re not entirely sold on that line of argument, we have previously made clear that decades worth of anti-suicide measures seem to have done little to affect America’s overall suicide rate. So clearly whatever we’re doing now isn’t working as well as we’d hope.

Gramsci // Dec 15, 2009 at 9:41 am

The only psychological explanation I could think of would be that an increased number of bridges drains the singular, symbolic grandeur from the one “perfect” place to jump. If bridges are common and ordinary, then perhaps your jump would seem more quotidian too.

This bridge needs some de-romanticizing, clearly:

http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2003/10/13/031013fa_fact

omellet // Dec 15, 2009 at 9:47 am

@Gramsci: I came in here to post that same article, you beat me to the punch. But I don’t believe it means you can’t have scenic bridges, but that you just have to make it difficult for somebody to kill himself by leaping from it.

Gramsci // Dec 15, 2009 at 10:35 am

What we should do is wheatpaste bridges across the country with pictures of the Golden Gate Bridge (“Go West, Jumper”), and then make the Golden Gate unjumpable.

Brendan I. Koerner // Dec 15, 2009 at 11:15 am

That Golden Gate Bridge piece is a classic. I actually posted about it back in June, on the heels of Roh Moo-hyun’s suicide:

https://microkhan.com/2009/06/05/the-one-thing-you-cant-fix/

Suicide in Sri Lanka // Aug 17, 2010 at 11:30 am

[…] previous posts about suicide haven’t been particularly cheery, and not just because of the grim subject matter. Everything […]