Nations at odds have long resorted to counterfeiting one another’s currencies, on the theory that doing so can severely undermine a foe’s economy. But the tactic just doesn’t sting like it used to, in part because cash is so less essential today, but also because the increasing sophistication of anti-counterfeiting technology has made the gambit incredibly expensive. Manufacturing a high-quality $100 bill is now estimated to cost $50, which means achieving any meaningful destabilization of the American economy (which has roughly $575 billion in currency swimming about) would require the sort of investment that’s beyond the reach of our most ardent enemies.

That hasn’t stopped the likes of North Korea and Iran from churning out vast piles of U.S. currency. But despite occasional misinformed handwringing over alleged “supernotes,” the toll just hasn’t been that ruinous:

We develop upper and lower bound estimates for the quantity of counterfeit dollars in circulation. Processing data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York suggest a lower bound of $12 to $14 million in value terms. Using denomination-specific weights to scale up the lower- bound estimate to account for the counterfeits passed outside the Federal Reserve yields an upper-bound estimate of $67 to $108 million, or about $1 to $1.50 per $10,000 in circulation. We believe that an estimate in the neighborhood of $40 to $50 million, or 60 to 80 cents per $10,000 in circulation, is the most plausible, and is consistent with a relatively short average lifespan for a given counterfeit note. These figures are relatively small, but for U.S. consumers, the threat from high-quality counterfeits is even smaller: for the $20 and smaller denominations, counterfeiting losses are tiny, at $7 million in 2002, of which less than $220,000 were notes that could not be detected by users with minimal hand inspection.

We further find that while it is indeed possible that a large number of counterfeits could be injected into the financial system, it is quite unlikely that they would remain there in use and undetected. We find the close correlation between the country distribution of the counterfeits detected by the Federal Reserve and the Secret Service particularly intriguing; we believe it is strong evidence that both counterfeit detection and incidence fall within a small range of about one note in 10,000 throughout countries where dollars are in circulation.

In other words, sleep soundly tonight—the printing presses of Pyongyang will never bring us down.

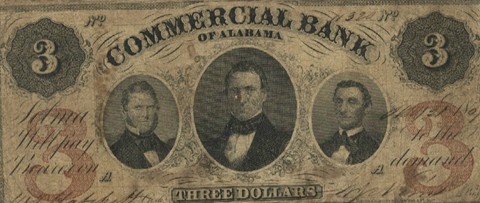

Oh, and we realize the $3 bill shown above is not technically counterfeit—just a pre-Civil War relic, printed when Alabama was an outcast from the American monetary system. The whole long, boring story is told here.

minderbender // Feb 9, 2010 at 11:54 am

It seems plausible that our adversaries couldn’t immediately raise enough capital to destabilize our economy, but we’re talking about a profitable enterprise (turning $50 into $100). Surely they could ramp up production over time?

What I want is for someone to write a political/strategic thriller in which the US president, hampered by high unemployment and an uncooperative (inflation hawk) Federal Reserve chairman, conspires with Iran to print a bunch of US money. Iran gets free money, the president gets monetary stimulus . . . but when an adventurous blog commenter stumbles on the truth, the world will find out if it is ready for . . .

Filthy Lucre

which somehow went from novel to movie over the course of this comment.

minderbender // Feb 9, 2010 at 11:59 am

Oh, and interestingly, the Secret Service has two mandates: protect the president, and fight counterfeiting. Filthy Lucre will make full use of the ironic potential here. Can the brave Americans tasked with maintaining the integrity of the dollar take down the one man they are sworn to protect? Find out in . . .

Filthy Lucre

Brendan I. Koerner // Feb 9, 2010 at 12:17 pm

@minderbender: On your first point, that $50 figure (taken from the same Fed report I quote from) only covers production costs. Then there’s the question of getting that cash into the American money supply. North Korean agents would be hard-pressed to pump in enough cash simply by purchasing American goods (a challenge in itself, given sanctions). So they’d have to find some middlemen to do their dirty work, and that would add to the cost—can’t sell those middlemen the bills for face value, of course. Plus there would inevitably be losses due to seizures. All in all, purely from a Machiavellian standpoint, NK is better off spending that money on nukes if they’re foremost aim is to upset the U.S.

As for “Filthy Lucre”–I think you’re on to something here. I can see Barry Levinson directing–an update on “Wag the Dog,” of sorts. Gotta have a sexy economist love interest, though–can Megan Fox play a Fed lackey?

Cashed Out // Feb 11, 2010 at 10:01 am

[…] few days back, we touched on the challenges of undermining one’s enemy by counterfeiting his currency. Today we’d […]