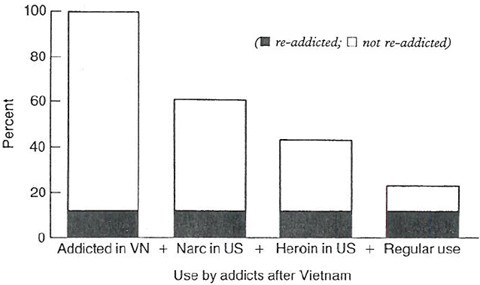

In keeping with our recent paying-gig focus on addiction science, we’d like to turn your attention toward the remarkable work of Lee N. Robins, who recently passed away. In the early 1970s, after hearing rumors that tens of thousands of Vietnam War veterans had come stumbling home as hopeless heroin addicts, Robins vowed to determine whether that was really the case. She found that although drug abuse had been alarmingly common on the battlefield, with a third of Army enlistees trying heroin and 20 percent suffering through the symptoms of addiction, everything changed once the soldiers came home. Remarkably, only a small percentage continued their drug use on the homefront, and those vets were a predictable lot—namely, men who had abused drugs prior to the war (see above).

After publishing her findings in 1973, Robins spent the rest of her career defending her contrarian conclusion regarding the real power of opiates. She always did so with unusually keen intelligence, as evidenced by this snippet from this 1993 lecture:

Beliefs about heroin based entirely on results in treated populations have created a self-fulfilling prophecy. Heroin is thought of, by law enforcement personnel and users alike, as the “worst” drug, virtually instantly and permanently addictive and creating craving so extreme that it overcomes all normal ability to resist temptations to theft and robber to acquire it. Users who share that view show by their use that they are ready to commit themselves to their concept of an addictive lifestyle. The public’s ranking of drugs with respect to “hardness’ probably has more to do with the drug’s legal status, the government’s commitment to discouraging its use, and its price than any intrinsic addictive liability. This is best demonstrated by tobacco, a highly addictive drug ranked as “soft.”

Robins was obviously trying to be provocative with that last statement, and she surely wouldn’t want heroin to be as easily accessible as cigarettes. But her point is valid, as far as treatment goes—could we more effectively wean users off heroin by treating them as no less “sick” than smokers who need the patch? Should the treatment of heroin addiction be normalized, so that those who’ve deigned to use the drug aren’t immediately shunted into a severe program that doesn’t address their underlying psychological issues?

minderbender // Feb 18, 2010 at 10:28 am

Reminds me of Malcolm Gladwell’s latest piece in the New Yorker (abstract here). The basic idea is that alcoholism may be much more a factor of culture (and less a factor of genetics) than is commonly thought. Same could be true of heroin addiction.

scottstev // Feb 18, 2010 at 11:41 am

To add a completely anecdotal and unsourced log to the pile, I remember reading an essay in the Village Voice where the author quit heroin quite easily and referred to withdrawal as nothing worse than a mild flu. I’m sure there are millions of folks who have done likewise and, because they haven’t f*cked up, aren’t in the system and aren’t counted in statistics.

Regarding the original post, I’ve seen anti-twelve step arguments mostly related to atheism. It’s strange, because the 12 steps (at least in the literature – each chapter may vary) have such a large tent when it comes to spirituality that you’d really have to be a die-hard materialist to object on those grounds.

Of course evidence for 12-step effectiveness is non-existent, and I’ve seen some Behavioral/Cognitive therapy web pages that argue against 12-step. I’m not sure if they’ve had better luck or not.

Brendan I. Koerner // Feb 18, 2010 at 12:03 pm

@minderbender: Been meaning to read that, given that it seems to germane to my current work. One thing that’s been turning me off: the antipathy I felt toward Gladwell’s recent piece comparing the NFL to dog fighting.

@scottstev: The whole debate over the efficacy of 12-step systems is endlessly fascinating. I’ve looked at a bunch of papers and studies regarding the method, and I still can’t make up my mind. From a research standpoint, the biggest problem is that you can’t design a randomized study for AA, NA, or any of the other 12-step groups. And there’s also the issue of self-selection–what comes first, the genuine commitment to achieving sobriety, or membership in one of those groups? It’s a tough call.

minderbender // Feb 18, 2010 at 2:09 pm

I think you just have to take Gladwell for what he is: a guy with unbelievable intellectual curiosity and a barely functioning BS filter. Often worth reading, but always with a generous helping of salt. The whole “Igon value” thing (Google it if you don’t know what I mean) is classic Gladwell. Laughable mistake, but you can’t help wanting to read the whole thing.

Brendan I. Koerner // Feb 18, 2010 at 2:35 pm

@minderbender: As a writer who spends much of his time trying to translate sci/tech jargon into plain English, I’m sympathetic to the challenges that Gladwell faces, and appreciative/envious of his great qualities (namely fluid prose, intellectual omnivorousness, and a sharp sense of humor). I didn’t like that NFL/dog fighting bit because it seemed like he worked backward from an obviously outrageous conclusion. Having made that same mistake several times in the past, I can tell you it rarely leads to good journalism.

Of course, I’m sure Gladwell doesn’t care about any of the criticism that he faces from the likes of Pinker, et. al. You develop pretty thick skin when (a la Rainier Wolfcastle) you get to sleep atop a great big pile of money with many beautiful women.

minderbender // Feb 18, 2010 at 4:49 pm

Working backward from an obviously outrageous conclusion is probably a good career move if nothing else. But it does strike me that his worst articles seem to follow that pattern (as in the infamous/ridiculous dependency ratio piece) while his best articles eschew it completely (I’m thinking about diapers and ketchup). Somewhere in between (but very solid) are the quasi-counterintuitive pieces like power law distributions and seatbelts.

But my problem is that once you’ve read one “dependency ratio” trainwreck, you can never really trust anything again. It’s a little bit like when you first encounter Felix Salmon writing about something you know about, and you say, “Oh, he doesn’t know what he’s talking about. I wonder if he knows anything about all those other things he’s written about?” Maybe. Maybe not.

Quagh // Jun 21, 2010 at 2:50 pm

They said the same things about Crack Cocaine as they did about heroin. I was able to walk away from crack after a few months. The same thing happened with Meth (after 3 years of use at that!) Alcohol on the other hand was a different matter.

Saw BK’s article in Wired. Good stuff. Total chaos reigns supreme in AA! (I’m a member too) Sometimes things work when the profit motive is taken out of it. However it is true that pressure exists to stay within the confines of the group. More of a pack mentality than a cult thing though.

Brendan I. Koerner // Jun 21, 2010 at 4:35 pm

@Quagh: Thanks for the feedback on the AA piece. I’ll be blogging about it a ton once the article goes live on Wired.com–hopefully later this week (starting 6/21). A lot of stuff got left on the cutting-room floor, given the complexity of the topic. I’ll be airing those tidbits in this space, so keep an eye peeled.