When conducting business deals with their fellow private citizens, people basically tend to be honest. Perhaps this is because we all secretly fear retribution and punishment, no matter how unlikely the consequences. Or maybe it’s just that we’re wired to realize that society can’t function if we’re constantly preoccupied with suspicion. Whatever the explanation, the bottom line is this: When you purchase something from a stranger, you can be reasonably certain that he or she will make good on their obligations.

When conducting business deals with their fellow private citizens, people basically tend to be honest. Perhaps this is because we all secretly fear retribution and punishment, no matter how unlikely the consequences. Or maybe it’s just that we’re wired to realize that society can’t function if we’re constantly preoccupied with suspicion. Whatever the explanation, the bottom line is this: When you purchase something from a stranger, you can be reasonably certain that he or she will make good on their obligations.

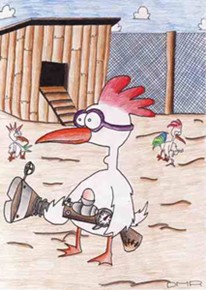

But the equation changes a whole bunch when the transaction isn’t between two citizens, but rather between a citizen and the government. In such a scenario, people tend to work the angles as much as possible, even if the consequences of getting caught can be dire. We were reminded of this curious fact upon reading an account of the Indonesian government’s efforts to rid a Borneo district of bird flu:

To protect local residents from the worst possibilities, a total of 7,000 infected chickens were culled.

Local authorities paid the owners a compensation of Rp12,500 (US$1.40) for every culled chicken, Endang said.

However, not all people welcomed the amount of compensation. Instead of giving up the positively infected chickens for culling, they hid the poultry and just handed over small chickens, he said.

As a result, the efforts to control and halt the spread of bird flu in Garut district were not so successful.

The first American parallel that popped to mind was the gaming of gun buyback programs, which have often been undermined by people who swap near-worthless firearms for disproportionate sums.

The main problem here, of course, is cynicism—a feeling among citizens that if there is no upside to playing by the government’s rules, since corruption or incompetence will ultimately cancel out any deal’s good intentions. That’s not an easy feeling to counter, especially since it’s often justified. (Eminent domain, anyone?) So maybe the only solution is to outsource buyback programs to private enterprise, who at least might be better equipped to determine fairer pricing than government bean counters. $1.40 per chicken strikes us as pretty low.

Jordan // Mar 9, 2010 at 2:50 pm

There’s a really good episode of Radiolab about Mortality where they talk about how chimps generally have the sense of “don’t kill your buddy” and “stuff should be distributed in a fairly equitable manner”. I have a feeling that face to face we have a really hard time ripping each other off because some of those notions are so deeply ingrained.

I also wonder how much lying goes on with respect to corporations, especially in medicine. Some months back I was planning on getting an STD test (hey, you can never be too safe) and it turned out that my insurance would only cover the battery of tests if I was showing symptoms. The doctor kept prodding me, asking if I had any kind of symptoms at all. Being the honest individual I am, I always said no, even though it was clear that the doctor was tacitly arguing that it was O.K. for me to defraud the insurance company. That sense of the system being built in an unfair fashion by a faceless entity probably explains a lot.

Brendan I. Koerner // Mar 9, 2010 at 3:57 pm

@Jordan: I’ve been in the same boat re: a doc wink-winking to me about committing obvious (albeit very minor) fraud. I guess there’s just a sense that health-care companies are so rich, and behave so greedily most of the time, that we should take what we can get. Total adversarial relationship, just like the one most folks have with that faceless entity known as government.

Agreed, there’s something deeply ingrained within our makeups that nudges us toward honesty. Fear of consequences isn’t enough to explain it.

minderbender // Mar 9, 2010 at 4:09 pm

I think this is not so much anti-government sentiment as it is the inherent difficulty of designing a good mechanism to achieve the desired results. Anup Malani has written about chicken culling – one problem is that culling drives up the price of the remaining chickens, meaning that it’s very expensive to pay enough to motivate farmers to turn over all their chickens voluntarily. And if you do shell out enough money to do the job, then it’s a huge windfall to farmers and they respond by stockpiling chickens for the next emergency.

It seems to me that the best way to do it is in two rounds. First round, compel farmers to sell you the chickens at the (pre-emergency) market price and destroy them. Second round, seize and destroy all remaining chickens for no compensation, and maybe punish the farmers for not turning them over in the first round.

Brendan I. Koerner // Mar 9, 2010 at 9:34 pm

@minderbender: Thanks a mil for the reference to the paper on the economics of chicken culling. May post about it later this week.

My solution? Squab.