Every member of our species naturally fears death, given that we can never satisfactorily answer the question of what comes next. And so we’ve invented a zillion different ways of coping with that anxiety, many of which involve rituals that confirm a belief in the spirit’s indestructibility. Few of these rituals, however, are quite as involved as those once practiced by the Yupik residents of St. Lawrence Island, a blip in the Bering Sea. Electing to participate in a pal’s funeral there used to require a serious commitment, as recounted in this wonderfully detailed history of Arctic body art:

Every member of our species naturally fears death, given that we can never satisfactorily answer the question of what comes next. And so we’ve invented a zillion different ways of coping with that anxiety, many of which involve rituals that confirm a belief in the spirit’s indestructibility. Few of these rituals, however, are quite as involved as those once practiced by the Yupik residents of St. Lawrence Island, a blip in the Bering Sea. Electing to participate in a pal’s funeral there used to require a serious commitment, as recounted in this wonderfully detailed history of Arctic body art:

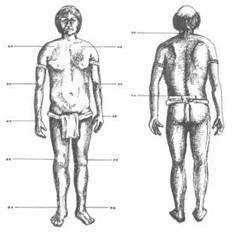

Funerary tattoos (nafluq) consisted of small dots at the convergence of various joints: shoulders, elbows, hip, wrist, knee, ankle, neck, and waist joints. For applying them, the female tattooist, in cases of both men and women, used a large, skin-sewing needle with whale sinew dipped into a mixture of lubricating seal oil, urine, and lampblack scraped from a cooking pot. Lifting a fold of skin she passed the needle through one side and out the other, leaving two “spots” under the epidermis.

These tattoos protected a pallbearer from spiritual attack. Death was characterized as a dangerous time in which the living could become possessed by the “shade” or malevolent spirit of the deceased. A spirit of the dead was believed to linger for some time in the vicinity of its former village. Though not visible to all, the “shade” was conceived as an absolute material double of the corpse. And because pallbearers were in direct contact with this spiritual entity, they were ritualistically tattooed to repel it. Their joints became the locus of tattoo because it was believed that the evil spirit entered the body at these points, as they were the seats of the soul(s). Urine and tattoo pigments, as the nexus of dynamic and apotropaic power, prevented the evil spirit from penetrating the pallbearer’s body.

Intriguing that the Yupik’s belief in malevolent shades so closely parallels the doppelgänger concept from Western European folklore. We reckon there’s a neurobiological basis for this similarity—that regardless of social background, human beings are prone to visual hallucinations designed to make sense of the senseless. And when dealing with the central mystery of existence, it naturally follows that our brains will opt for the easiest deception: Showing us the people that we’d seen in the flesh just weeks or days before.

scottstev // Apr 21, 2010 at 4:37 pm

I really dig the concept of “Shade.” It sounds a lot like “Gloom” in Day watch .