A treasured Friend o’ Microkhan recently directed us toward this insightful yet depressing Foreign Policy piece, about the seemingly endless nature of Africa’s various armed conflicts. The author makes a convincing case that we do ourselves a disservice by trying to understand these ultra-violent clashes as wars, since one side usually has no interest in seeking peace. In other words, an outfit such as the Lord’s Resistance Army shouldn’t be viewed as an army at all, but rather a criminal enterprise whose power is perpetuated only by continued strife.

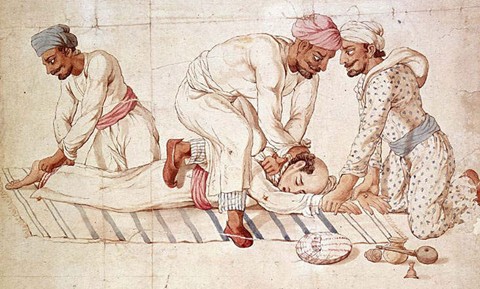

This cogent argument made us think of what might be construed as the LRA’s early 19th century equivalent: The Thuggees of India, immortalized in pop culture by that infamous heart scene in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. The British firmly believed that the Thuggees were an organized movement dedicated to the veneration of the goddess Kali, who allegedly demanded human sacrifice. The Thuggees were thus blamed for tens of thousands of ritual strangulations, usually involving ceremonial yellow scarves. The British so feared this “movement” that they organized a systematic campaign of suppression, under the notoriously brutal William Henry Sleeman.

But did the British err in perceiving thuggee as an organized movement with clear goals, much like the well-intentioned souls who believe that Africa’s rebel movements have an interest in peace? Kim Wagner has dedicated much of his career to arguing that the thuggees were not sinister cultists, but rather simple (albeit vicious) bandits. The essence of his thesis can be found here:

I feel it safe to assert that travellers were strangled and plundered by bands of robbers in early 19th century India if not earlier…The men involved were part of the military labour market, sometimes joining larger armies and sometimes serving petty zemindars, and when faced with demobilization they had to find other ways of gaining a livelihood. In other words, Thuggee was the continuation of a predatory lifestyle under well-regulated circumstances by men thus deprived of the means for open plunder. As opposed to Sleeman’s claim being a thug was not a caste-like identity, thuggee was not motivated by religious zeal and it was certainly not centrally organized.

You can see, then, why the thuggee narrative made sense for the British. It was much easier to sell the paymasters back in London on an anti-cultist drive than a crusade against part-time bandits who occasionally staffed the very militias critical to the Empire’s local control.

Oh, and don’t forget, the thuggee riff made for excellent copy. The Tom Clancy of the late 1830s was a man named Phillip Meadows Taylor, and his most sensational best seller was Confessions of a Thug. Maybe it’s just us, but Confessions of a Temporarily Demobilized Soldier doesn’t have quite the same ring to it.

(Image via Columbia University)

Jordan // May 6, 2010 at 2:59 pm

I tend to agree with the consensus arrived at in the post on Ta-Nehisi’s blog that while the piece makes some interesting points, it’s conclusions are rather suspect given the gross generalization (trying to generalize anything about a continent as large and diverse as Africa is necessarily fraught with problems) and sensationalism (talking up the “violent thugs” angle makes for better copy).

With that said, it does seem that we generally have a difficult time understanding the motivations of non-state actors. Central Africa is especially fraught because conflicts tend to spill across borders with frightening ease and so the motivations in one conflict will get wrapped up in the motivations of another. For instance, in Congo a lot of the “rebel” groups are composed of or led by former Hutu leaders from Rwanda who were instrumental in the early-90s genocide. They managed to slip away in the mass of refugees and are now building up power through violence in an effort to avoid being brought to justice.

Violence on that scale is almost never the result of destruction for the sake of destruction. There just aren’t enough people who are really that crazy or willing to ignore the potential consequences (getting shot by government troops). They want something. Figuring out how best to get people what they want so they can live in (relative) peace is, however, easier said than done.

Brendan I. Koerner // May 6, 2010 at 3:30 pm

@Jordan: Will have to check out the discussion on Ta-Nehisi’s blog. Missed that somehow.

In its original incarnation, the LRA allegedly wanted to govern Uganda according to Biblical law (whatever that means). But at this point, I think Gettleman’s take is correct–the movement seems entirely disinterested in governance, or any sort of participatory role in shaping the nation’s future. Perhaps the foot soldiers are led to believe otherwise, but I don’t think the leaders actually have any dreams of someday marching on Kampala–or, for that matter, of negotiating peace with the current regime. Joseph Kony does not strike me as the Khun Sa sort, who will someday retire to become a gentleman farmer in the hills.