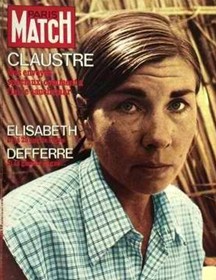

Last week I chimed in about the seemingly never-ending quest to bring deposed Chadian dictator Hissène Habré to justice. To add to that sad story, it’s worth remembering how Habré first gained international notoriety: the 1974 kidnapping of French archaeologist Francoise Claustre, who was held for nearly three years before gaining her release through the intervention of Libyan strongman Muammar Gaddafi. Known to the French as L’affaire Claustre, the entire kidnapping saga was a clusterfuck of the highest order. When Claustre’s husband flew to the Chadian desert in 1975 to negotiate with Habré, he, too, was taken hostage. Then the French government paid a multimillion-dollar ransom, only to have Habré pocket the money and hang on to his captives. By the time the ordeal was over, Habré was not only extremely wealthy by Chadian standards, but also a folk hero for outwitting the nation’s former colonial master. The year after Claustre’s release, he was named Chad’s prime minister—quite an achievement for a desert guerrilla.

Last week I chimed in about the seemingly never-ending quest to bring deposed Chadian dictator Hissène Habré to justice. To add to that sad story, it’s worth remembering how Habré first gained international notoriety: the 1974 kidnapping of French archaeologist Francoise Claustre, who was held for nearly three years before gaining her release through the intervention of Libyan strongman Muammar Gaddafi. Known to the French as L’affaire Claustre, the entire kidnapping saga was a clusterfuck of the highest order. When Claustre’s husband flew to the Chadian desert in 1975 to negotiate with Habré, he, too, was taken hostage. Then the French government paid a multimillion-dollar ransom, only to have Habré pocket the money and hang on to his captives. By the time the ordeal was over, Habré was not only extremely wealthy by Chadian standards, but also a folk hero for outwitting the nation’s former colonial master. The year after Claustre’s release, he was named Chad’s prime minister—quite an achievement for a desert guerrilla.

What fascinates me about this case isn’t necessarily how it bolstered Habré’s political fortunes, though, but rather how Claustre managed to endure her long, terrible captivity. It was never easy:

She told one interviewer she contemplated suicide because her life had become so desolate. She told another the biggest treat she and her husband, who was kept in a separate enclosure, had was the camel meat that occasionally spiced up their diet of rice, vegetables and fruit.

Yet as an academic at heart, Claustre also did her best to keep learning while imprisoned in the desert:

While a captive, Mme. Claustre said, she taught herself to read and write Toubou, the language of the rebels, and performed normal cooking and cleaning chores done by Toubou women. “They understood my distress,” she said. “And I tried as much as I could to integrate myself into their family life.”

This may sound ghoulish, but I think there is much to be learned about human psychology by studying how people respond to traumatic circumstances such as extended captivity—especially in non-judicial situations such as the one faced by Claustre, in which the outcome is never certain. People have all sorts of different coping mechanisms, of course—I’ve always been struck, for example, how much Terry Anderson relied on religious faith to see him through his seven-year ordeal in Beirut. But those who survive the experience all seem to share one common trait: a notable lack of self-pity. That’s not to imply that they don’t feel bitterness, toward both their captors and those back home who seem to be sitting on their hands. But to pull through that sort of sudden, undeserved loss of freedom, one cannot dwell too long on what might have been.

Gramsci // Aug 3, 2010 at 7:20 pm

Reminds me of Kobo Abe’s novel (later a good movie in its own right) “Woman in the Dunes.”

ADW // Aug 4, 2010 at 12:50 pm

Self pity has to take a back seat to a certain gratitude about just being alive, IMO. Tightening the emotional belt, so to speak. As far as the camel meat, even though it sounds unappealing, but I know i’d eat it if it meant staying alive.

I don’t think there’s anything ghoulish about an interest in trauma psychology. Not only is it interesting, but a lot can be gained by examining what makes one person survive versus another. I was thinking about that last week after Duch came up, about how the two women I referenced have done very well for themselves in the states. They’ve gone on to create happiness and financial stability in spite of the horrible situation from which they came. I don’t know that the answer is complicated or as simple as putting one foot in front of the other, and continuing to walk. Maybe there’s some magic in deciding to live, no matter what.

Brendan I. Koerner // Aug 4, 2010 at 1:44 pm

@ADW: Excellent comment. Yes, I think there’s a lot to be learned from examining how different people respond to trauma, and using those observations to determine what can help us triumph over extreme adversity. This is actually a theme I’ll be exploring in my next book–specifically related to methods for dealing with PTSD. Expect a lot more posts on this topic in the coming days/weeks/months/years.

ADW // Aug 4, 2010 at 4:41 pm

@BK,

I know a little bit more about the issue than I’d like to, but I am fascinated. I don’t want to get into the story (not sexual abuse; I don’t even know why I feel the need to say that but I do), but the most interesting part of examining trauma re my own experience at age eight is that I completely disconnected myself to get through, and only now am I figuring out how truly disconnected I’ve been several years later. But, the residual disconnect impacted both the bad and good things that entered my life. I know the experience effected me, which would be quite obvious to anyone hearing the story, but I couldn’t feel it. Instead, it manifested itself as acting out the story in various arenas through a variety of ways. It’s like watching a bad movie but you can’t connect to the main character. I’d always been attracted to danger which in some way led to the story, but afterward it got worse. I did some really dumb things that make me grateful to be alive today. And, then there’s the thing of seeking out other damaged people, other members of the tribe. A&E’s Intervention does a good job of exposing the effects of trauma. Bad thing happens to young or adolescent child, adolescent child numbs out with drugs/alcohol. Certainly, there are people who escape in tact. I’ve fucked up a lot, but I still managed to crawl through undergrad and grad school, and though I’ve done drugs, I never became addicted. Again, I’m very grateful, because at any point the outcome could’ve been very different. Something happened recently that forced me to re-examine the original events. I had so many things wrong. A child’s mine often distort events, I suppose, or maybe it’s that trauma distorts the human psyche. I found out that what I had believed for so many years, something I tortured myself over, wasn’t even true. I’m carrying guilt and shame, and the blame wasn’t cast in my direction in the first place. The problem – I’m so used to thinking this way that I don’t know another way, and I’m presently trying figure my new self out. Please do keep in mind as you research for your book that many trauma survivors look perfectly normal on the outside, and sometimes it takes years for symptoms to manifest. I’m sure you’ve already thought of that, but i wanted to mention it.

I look forward to more posts.

Brendan I. Koerner // Aug 4, 2010 at 4:52 pm

@ADW: Many thanks for the deeply personal feedback.

I think we’re just now beginning to appreciate the neurobiological distinctions between the brains of children and adults. Coping mechanisms are different because kids have brains that are still forming, and so resort to more cut-and-dry methods. Disassociation is certainly a biggie–the sense that, “Everything’s alright because that didn’t really happen to me.” But I think that gets harder to do as the brain develops a more coherent sense of self during adolescence.

ADW // Aug 4, 2010 at 5:36 pm

@BK,

Yes, the age at which the trauma occurs makes a big difference. Childhood trauma can easily become integrated into an identity not fully developed. Now, you really have me interested because most of the people I know who suffered trauma, suffered childhood trauma prior to age 11/12. Other than those I’ve met who fled war torn countries, I don’t think I know anyone who has suffered PTSD as an adult. I do know it’s quite common in the military for obvious reasons, but I can’t recall many other stories.

I’ll admit the experience is a little weird for me because I discover new things everyday. Although, only recently have I been able to cop to the trauma openly, I can spot someone who’s suffered it with lightening quick speed. “Name the trauma” is something I’ve done, not intentionally or maliciously, but, accurately over the years. But, again, most of it has been childhood trauma.

When Best Intentions Fall Flat // Aug 5, 2010 at 10:43 am

[…] issue actually came up in some recent Microkhan comments. Children and adults have different ways of coping with the world in large part because their […]