I distinctly remember the first time I was surprised by a geographical truth that ordinary maps conceal. I was about ten years old, and thought of myself as pretty sharp when it comes to map-related matters. Seeking to impress my pops with my knowledge, I mentioned at the dinner table one night that Maine was the northernmost state in the Lower 48. He quickly corrected me, and ran to fetch an encyclopedia volume to prove his point. Sure enough, the flat map by our classroom blackboard had lied to me: the northern tip of Maine is on the same latitude as Seattle’s southern suburbs. Rainy Washington, rather than icy Maine, wins the prize.

I might not have embarrassed myself like that if Richard Edes Harrison had been allowed to have a greater impact on our educational system. A nearly forgotten legend of cartography, Harrison made his name creating beautifully detailed maps for Fortune throughout the magazine’s 1930s and ’40s heyday. (The graphic-design geniuses at my employer Wired are much in his debt.) Harrison’s masterstroke was to recognize how aerial intelligence had changed the art of mapmaking, revealing the contours of a planet that defies our species’ natural prejudices regarding direction. This 1944 LIFE profile describes his special knack for defying expectations:

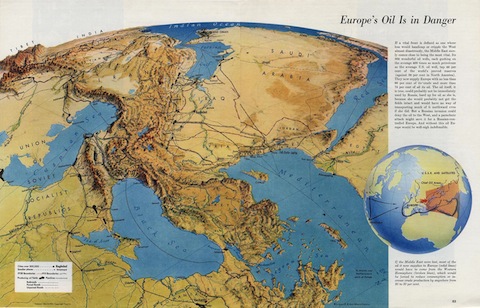

In a perspective map a part of the world is seen from a vantage point high above the earth so that the distances draw together in perspective, as they might to an incredibly farsighted man poised at an altitude of many thousand miles. Perspectives are not new to map technique but they have rarely been done so accurately and artfully as Harrison does them. One of their special advantages lies n the way they break the cartographic convention of showing the world with the top of the map inevitably north, the bottom inevitably south. Although this convention is useful, Harrison feels is is grossly overdone. The perspective maps are based on the obvious truth that the shapes of countries and continents change their look when the point of view changes…

Anybody can improve his geographical sense, Harrison says, simply by taking a map and turning it upside down or sideways. Harrison is always up in arms against the academic cartographers who stubbornly refuse to break away from conventions. He is also thoroughly annoyed at careless American who refuse to see fact that maps show them. He has found, for example, that most people are utterly surprised when told that all of South America lies east of Jacksonville, Fla. He has also discovered that almost everybody will give him two-to-one odds that Venice is south of Vladivostok (it is actually 150 miles farther north).

I do wonder about the particular mental gift that allowed Harrison to be such a groundbreaker in his chosen profession. I think it can probably best be characterized as spatial intelligence—an innate sense of how objects relate to one another in three dimensions. In the sporting realm, he might have made a very fine stock-car racer.

Another great Harrison map, of 1930s Ethiopia, is available here.

Update: A kind correspondent alerts us to the fact that there is a Lower 48 locale even farther north than Washington’s roof: Northwest Angle, Minnesota.

TIM FERNHOLZ // Dec 19, 2010 at 3:04 pm

[…] a key exemplar for your humble blogger here, sings the praises of an old-school cartographer, Richard Edes Harrison: He is also thoroughly annoyed at careless […]