On Christmas Night, the ingestion of too much fine red wine led the Grand Empress and I to spend a pleasant few minutes researching Thrinaxodon, one of the many Therapsids to be found in mankind’s evolutionary tree. We were intrigued to find great disagreement on what this critter looked like; due to a paucity of fossil evidence, artists have been free to imagine the mammal-like reptile as either a lovable otter-like creature or something akin to a slimmed-down wolverine. Will we ever be able to determine which artistic interpretation is closest to the way Thrinaxodon really looked?

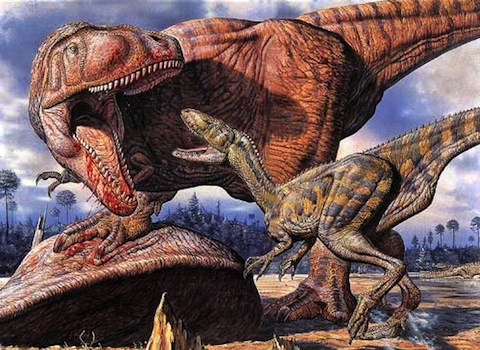

Sealed inside by the snow on Boxing Day, I decided to do a little digging into the creative process for paleoartists. I didn’t have to dig very deep, fortunately, thanks to this great collection of interviews with contemporary masters of the form. Lots of great stuff here, including links to the works of such paleoart stars as Mark Hallett (see above) and Mike Skrepnick. But what I really zeroed in on was the Q&A with Mark Witton, who did an excellent job of explaining what makes a piece of paleoart worth your while:

The success of a palaeoart piece is determined through both its scientific and artistic merit, and the science is often the easier part to get right. With a complete skeleton, we can probably assume the rough body contours of an extinct animal to a reasonable degree of accuracy. Our record of soft-tissues is improving markedly, too, so even the detailed external anatomy of some long-dead animals can be restored in some detail. The science of palaeoart, then, simply relies on paying attention to the data available on given taxa: proportions, soft-tissues where known, footprint and trackway data and whathaveyou. We’re going to have some of this data superseded by other finds later, but we can definitely be ‘correct’ when we’re putting paint on the canvas.

Thing is, anyone who can use a ruler and a pencil can bring this information together and knock up a basic reconstruction of an extinct animal: in some respects, it almost has more in common with technical drawing than it does artistry. It has, indeed, led to the Dreaded Recurrence of Flat Views flowing through a fair amount of palaeoart: there’s a whole bunch of palaeoart images with dead-on lateral or anterior views of animal heads or bodies. Inspired, I suppose, by Paul-esque reconstructions of skeletons in multiple views, they look more like technical reconstructions dropped on top of painted landscapes than natural scenes. They’re great bits of art, mind: they look like 2D cutouts arranged on a stage, with even the backgrounds having a similar theatre-set feel to them, but they’re too stylised to persuade the viewers, even if only in a minor way, that the artist was actually there, witnessing these ancient scenes himself. This is where the artistic prowess of the best palaeoartists comes in: they take the schematic technical work of scientists and turn it into something dynamic and vital. Something composited into a realistic environment and interacting convincingly with other animals. Purely artistic skills – a sense of composition, use of shading, the position of the PoV, the colour palate – are what gives the picture presence and really grab the imagination of the viewer. Even the most striking, fantastic-looking critters will lose their effect in artwork if they’re poorly lit, positioned awkwardly within the frame or postured in an obscuring way. In this respect, palaeoart is identical to other forms of representative art: the artist needs to understand the form of their subject, how they would appear in a realistic environment, and then wrap it all up in a dramatic, stylish way. Think about John Gurche’s work, for instance: his knowledge of form, use of light and depth of field makes it look like he’s photographing enormous animals from 75 million years ago: it’s like he’s there, man. If you can trick your audience into that (and his work did, indeed, do this to a younger version of myself), you know you’ve done your job.

As someone who was deeply influenced by the dinosaur art of Rudolph Zallinger as a young’un, it’s tough to realize that Microkhan Jr. will grow up with a very different mental picture of what ancient animals looked like. And that’s due not only to changes in paleontology, but also to the rapid evolution of paleoart. The big question, then, is how the artists influence the scientists—there’s just no way that a paleontologist can avoid being influenced by the painting and drawings that first got him or her interested in the field.

Jordan // Dec 28, 2010 at 4:42 pm

Not to mention the name changes. A lot of people I know are still sad that Brontosaurus is gone.

Also, looking up random stuff on the internet is a great way to pass the time. I killed some on Sunday learning about Brucellosis, the bacteria infection that killed Lincoln’s mama. The guy who discovered that it was often caused by unpasturized milk, Themistocles Zammit, has one of the most awesome names ever.

Brendan I. Koerner // Dec 28, 2010 at 8:12 pm

@Jordan: Agreed on the pleasures of random research on The Tubes. But it’s not just fun and games–going off on those tangents can help me work through mental blocks, too. Don’t think I could overcome a lot of creative hurdles were it not for the occasional–okay, more than occasional–study break in which I learn about Thrinaxodons.

Had to look up T. Zammit, which led me to discover that he was also a Maltese knight. The man is zooming up my cool list…

Justin // Dec 29, 2010 at 10:50 pm

The Last Dinosaur Book by W. J. T. Mitchell has beautiful color plates and a fascinating scholarly analysis of paleoart. Google books link below.

http://tinyurl.com/37hqb5a

Brendan I. Koerner // Dec 30, 2010 at 3:14 pm

@Justin: Thanks for the rec on the Mitchell book. Love that cover–always a sucker for action shots of long-necked dinos–so will have to check out the whole thing.