A salient reminder that engineering details really matter, from the august (and 141-year-old) pages of The Field Quarterly Magazine and Review:

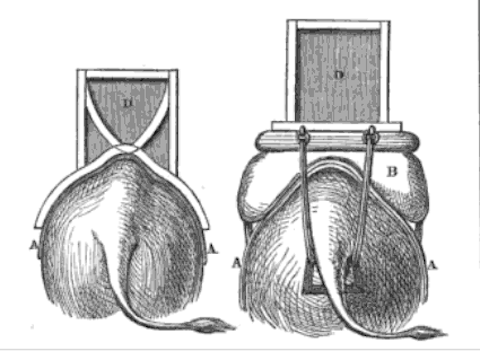

The Hindustani howdah often requires six men to place it on the elephant’s padded back. The Siamese “shing kha” can be easily lifted by two persons, and this while the elephant is standing—a great advantage, especially on stony ground. The difference of weight also is such, that a Burman or Siamese elephant is comparatively fresh when the heavily caparisoned Bengal animal is quite done up for the day. All this difference, to the advantage of the shing kha, arises simply from its being made on the principle of the saddle tree, and so fitting home to the sides of the elephant’s back; whereas the howdah, being built on a flat frame, rests balanced on the animal’s vertebrae, and has to be propped and cushioned on each side of that ridge. The preceding diagram shows clearly enough the superiority in lightness and tenacity of the former vehicle as compared with the latter.

It will take a great student of Asian military history to comment on whether this design advantage somehow influenced the diverging fates of India and Thailand once European colonialists turned their eyes eastward. But if the stirrup can be credibly credited with making the Mongol Empire possible, it’s no great stretch to think that the shing kha helped shape Thailand’s political fortunes to some extent. Seemingly minor technological advantages can have profound impacts over time.

Like gas stations in rural Texas after 10 pm, comments are closed.