One of my favorite Ponzi schemes of recent vintage was Pigeon King International, which convinced thousands of cash-strapped farmers to raise so-called “rats of the sky” in backyard pens. The scam’s mastermind, Arlan Galbraith, claimed that poultry-loving North Americans were on the verge of falling in love with roasted squab, and that farmers who bred his birds would soon be rich beyond their wildest dreams.

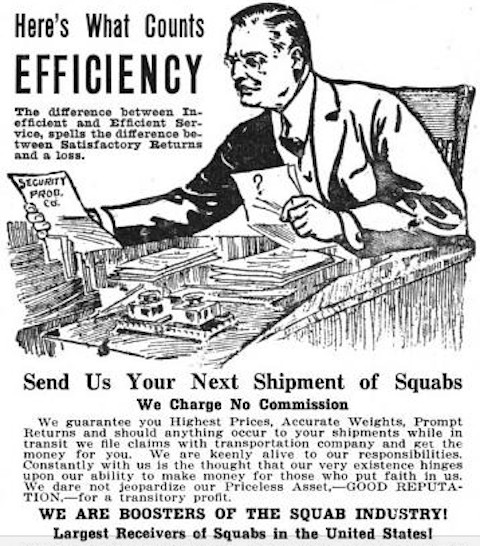

Had the scheme’s victims bothered to look back at the history of squab farming, they would have quickly realized that Galbraith was a con man. This was not the first time that men and women had been artfully duped by salesman stating that the Squab Renaissance was about to occur. In the 1920s, there was a massive squab bubble in the United States, as dozens of companies popped up to offer their services as bird brokers. Newspapers published regular reports on squab prices, and passed along the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s assurances that this time, the forthcoming squab boom would really, truly happen:

Many years ago, a wave of enthusiasm over squab raising swept the country. Fabulous profits were told of and many people bought breeding stock and expected to make a fortune with little work in a short time. When they discovered that these figures were overestimated and that to reap a profit regular care must be given the birds, their interest slackened and they talked as much against the proposition as they had for it in the beginning.

As a matter of fact, pigeon raising can be conducted successfully as a special business, but is better adapted to serve as a side issue on a small scale in towns and cities and on general farms. The demand for squabs, especially in large cities, is increasing. Squabs are often used to replace dressed game, which is decreasing in this country.

We all know how this story turns out, of course: the chicken became king of America’s dinner table, while the squab remained a curiosity—perhaps because people aren’t too eager to consume the cousins of the birds they see eating garbage at the park.

So why does each generation seem to fall for the squab scam anew? I think a big part of the explanation is our willingness to believe that the march of technology will inevitably smooth out all problems. A big part of PKI’s come-on was that new breeding and feeding techniques had made it possible for farmers to squeeze out more meat per invested dollar. This is exactly what the USDA told squab hopefuls back in the 1920s—that past failures of the squab industry were attributable to the fact that breeders lost too many pigeons to disease, or didn’t have the genetic know-how to create the fattest birds possible. People fall for these lines, even in the absence of evidence, because we do trust that science is not only constantly advancing, but that it’s advancing in all areas, no matter how obscure. And their assumption is that at some point, amateurs will inevitably be able to get the same results as committed professionals—and, in the process, be able to overcome the laws of supply and demand, to boot.

Should any aspiring squab breeders reach this post in the course of your research, I encourage you to check out this Jazz Age publication. And then consider why its author, F. Arthur Hazard, appears to have no other indelible mark on history.

Captured Shadow // Apr 7, 2011 at 1:02 pm

Seems like other livestock have had similar bubbles, Llamas and Emu’s come to mind. Time it right and you might make a mint……

Brendan I. Koerner // Apr 7, 2011 at 1:12 pm

@Captured Shadow: The one that immediately popped to mind was worms. There have been a lot of vermiculture scams over the years.

Jordan // Apr 8, 2011 at 12:50 am

Hey, if you can have economic bubbles over tulips, anything is possible.