Writing about the hammer throw has got me thinking a lot about Soviet Bloc athletics, and in turn one of the phenomena that fascinated me during my youth: East-to-West defectors. I was always drawn to tales of sportsmen from the other side of the Iron Curtain who decided to chuck it all and start anew in the NATO-land. A big part of the appeal was my sense that these defectors, in their own bizarre way, living the quintessential American dream, which is all about personal reinvention. (Jay Gatz, anyone?) To a grade schooler who didn’t quite understand the importance of family ties and the psychological comforts of home, bolting from one’s hotel during a competition and seeking asylum at the closest Western embassy seemed like the grandest of grand adventures.

Writing about the hammer throw has got me thinking a lot about Soviet Bloc athletics, and in turn one of the phenomena that fascinated me during my youth: East-to-West defectors. I was always drawn to tales of sportsmen from the other side of the Iron Curtain who decided to chuck it all and start anew in the NATO-land. A big part of the appeal was my sense that these defectors, in their own bizarre way, living the quintessential American dream, which is all about personal reinvention. (Jay Gatz, anyone?) To a grade schooler who didn’t quite understand the importance of family ties and the psychological comforts of home, bolting from one’s hotel during a competition and seeking asylum at the closest Western embassy seemed like the grandest of grand adventures.

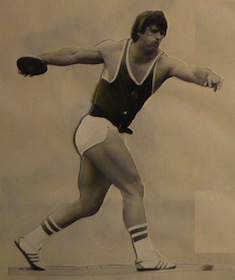

One tale that stuck in my mind was that of the East German discus thrower Wolfgang Schmidt (right). After flubbing an escape attempt, Schmidt was tossed in jail for over a year, after which he was declared Sportverbot—forbidden from ever again practicing the athletic craft to which he had dedicated his young life. This fantastic Sports Ilustrated account of Schmidt’s tribulations and eventual is a longread well worth your time. A typically awesome (and disturbing) snippet:

Wolfgang Schmidt—decorated superstar of the German Democratic Republic, holder of the world record in the discus throw, possessor of an Olympic silver medal, owner of two Orders of Merit of the Fatherland—groaned in pain as he stretched out on his bed of boards and fought to keep himself from going insane. “I played a mind game with myself, pretending that I was only an actor making a film about prison and that the shooting schedule was dragging out longer than it should, but that nothing could be done about it. I also relived all my memories, my visits abroad, my conversations with old friends in the West. Sometime around the seventh day of my second 10 days in solitary, Wiedemann came from Berlin. We did not meet in my stinking cell. He summoned me to an office downstairs. There, he berated me: ‘Have you gone crazy? Do you want to add two years to your sentence? I suggest you withdraw the exit visa request.’ ”

Schmidt was alarmed, but he did not rescind the application. When he was released at the end of his second 10 days in solitary, he had lost 13 pounds, and his back was still sore from the beating as well as from sleeping on boards for so long. He returned to a cold reception from his cellmates. “They did not offer sympathy,” he recalled. “Most of them had disliked me because I was famous and had seen the world. When I got into trouble, most of them were gloating that the authorities had punished a decorated athlete who had lived better than they.”

Schmidt returned to the bleak routines of the KFZ, but he felt something strange in the air—a sense that people were watching him, waiting for something. Finally, Zidorn told him that the word was out that the authorities had decided to break Schmidt for good unless he withdrew his exit visa application. “They’ll never let you leave the country, Wolfgang,” said the swindler. “They’ll put you in solitary again and again.”

Frightened at the thought of another stretch of solitary, Schmidt notified Wiedemann that he had changed his mind about leaving the G.D.R. The Stasi insisted that Schmidt put his decision in writing. He wrote verbatim what Wiedemann dictated: “Herewith I withdraw my application for an exit visa. It is my wish to work in the G.D.R. as a coach in the throwing events or as the caretaker of a fitness club.” Wiedemann insisted that Schmidt add, “My decision is voluntary.”

More on the glamour of Cold War defection shortly, once I get a bit farther along in this draft.

Like gas stations in rural Texas after 10 pm, comments are closed.