One of the most interesting aspects of researching my slot-machines yarn for Wired was the whole extradition angle. In fact, I’d daresay that’s what attracted me to the story in the first place—the fact that the United States government deemed the crime grave enough to go an fetch someone from Latvia, a country that had never before shipped one of its own into the maw of America’s judicial system. There were obviously some deep political considerations at work here, as well as a strong desire to send a message to Latvia’s criminal subculture. I’m sure it’s no coincidence that the raid on Rodolfo Rodriguez-Cabrera’s business took place, quite literally, mere hours after the signing of the first post-Soviet extradition treaty between Latvia and the U.S.

Since tackling the Wired project, I’ve taken a keen interest in extradition cases, especially those in which a serious crime in one country is nothing more than a misdemeanor in another. A perfect example is the ongoing case of Brian and Kerry Ann Howes, a Scottish couple who once ran a chemical supply company. The U.S. government alleges that they sold red phosphorous and iodine to many methamphetamine manufacturers on these shores, and it now looks like the Howes will be extradited to Arizona to stand trial:

Brian and Kerry Ann Howes, from Bo’ness, near Falkirk, are said to have sold legal chemicals which were then used to make illegal drugs in the US. The pair maintain they ran a legitimate business and have been fighting extradition for more than four years.

The pair were arrested by Central Scotland Police in 2007, amid claims they supplied more than 40 chemicals to dealers via the online company Lab Chemicals International. The charges against Mr and Mrs Howes allege they used their internet company to supply red phosphorous and iodine to 400 customers in the US, most of whom were producing methamphetamine, also known as crystal meth.

Red phosphorous and iodine are legal in Britain, but regulated in the US.

The case falls under the 2003 Extradition Act which allows the extradition of people to the US without any trial taking place in the UK, removing the need for US authorities to provide prima facie evidence of criminality…The allegations include deliberately mislabeling chemicals sent to the US in a bid to avoid detection.

To understand the case, it’s essential to read the American indictment, which contains specific details regarding the Howes’ alleged efforts to avoid detection. One major complicating factor is that the Howes initially responded in the legally correct way when confronted by an undercover DEA agent claiming to be running a meth lab: they cancelled his order. (When asked to ship to the same address some time later, however, the Howes complied.)

Based on my experiences reporting the Wired piece, I do think it’s impossible to make blanket statements about when extradition is appropriate and when it isn’t. Furthermore, if the information in the Howes indictment is correct, I think it’s safe to say they had a pretty good idea of how their wares were being used Stateside. Yet the fact remains that they were operating within the confines of British law. Wouldn’t American legal resources be better served trying to mend that discrepancy, rather than focusing on a single case that will do nothing to clear up the ambiguity on the books?

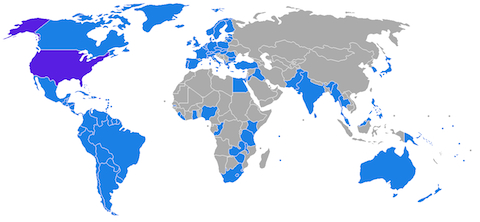

(Map above shows nations with which the U.S. has extradition treaties)

Like gas stations in rural Texas after 10 pm, comments are closed.