At the risk of alarming folks who have a vested interest in my creative progress, I must confess that the book-writing process is proceeding at a snail’s pace. In a wildly optimistic moment last month, I vowed to have two entire chapters done by Labor Day; now my best-case scenario is that I’ll have a single chapter done by day’s end, and even that isn’t a lock. The words flow much more quickly in theory than in practice.

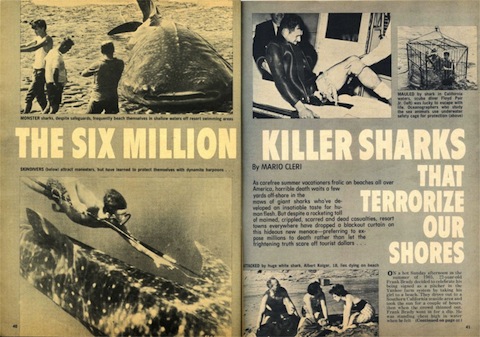

Yet as much as I’d like to convince myself that all writers endure such struggles, that simply isn’t the case. I found it alternately illuminating and dispiriting to read this terrific 1984 interview with The Godfather author Mario Puzo, who was nothing if not productive. Prior to finding his fortune in Hollywood, Puzo labored as a pulp-magazine writer, penning sensationalist clip jobs under the pseudonym Mario Cleri (above). He spoke of just how many pages he could dash off in the name of pulling a family-sustaining paycheck:

Q. How many pages of a book bonus could you write in a typical day?

PUZO: I used to do a book bonus on the weekends, which was at least 60 pages. I never could write in the office, I had to work at home. When I was working on The Godfather, I was doing three stories a month, I was writing book reviews for The New York Times, Book World, Time magazine, and I wrote a children’s book [The Runaway Summer of Davie Shaw]. All at one time. And I was publishing other articles. I had four years where I must have knocked out millions of words.

I tell ya, it’s absolutely the best training a writer could get, to work on those magazines. You did everything.

Q: There’s no equivalent today.

PUZO: It’s a shame. If I had a son who wanted to be a writer, I wouldn’t even bother to send him to college. I’d get him a job up there as an assistant editor, leave him there for five years and he’d know everything. You’ve got to turn out a lot of copy.

Also worth noting from the interview, especially given the subject matter of my book: Vietnam didn’t play in the pulp world:

Q. Did you ever write a story on Vietnam?

PUZO: Yeah, I did one or two, but they were absolute poison. The readers didn’t like to read about it. That was very early on in Vietnam. We used to emphasize that Vietnam only had poison sticks. How the Poison Stick Army Beat America’s Ultra-Modern Weapons, shit like that.

Q. But it never went over?

PUZO: Nah, they hated it. Also we weren’t the heroes. Just like the Korean War—we used to call that The No Fun War. World War II was The Fun War. And you could get some mileage out of the Civil War and World War I. World War II was a bonanza. But Korea and Vietnam were losers.

I wish the interview had delved a bit more deeply into the notion of what constitutes a “Fun War,” and whether such a thing is even possible in the age of mass communication. Copious information creates a thousand shades of moral gray.

Captured Shadow // Sep 6, 2011 at 12:59 pm

Writing for me is like pulling teeth. Issac Asimov is another author that supposedly cranked out the paragraphs. I was impressed when I heard Tom Robbins does a page per day. And if he gets done early -rewrites it to make it better.

I wonder how much writing volume reporting is real and how much is image management….

Brendan I. Koerner // Sep 6, 2011 at 4:51 pm

@Captured Shadow: I’ve never really tried my hand at fiction, but my hunch is that novelists work more quickly than us non-fiction hacks. I often get sidetracked by efforts to nail a particular fact–this morning, for example, I lost a good 20 minutes trying to identify the exact location of a 1950s housing development. (No luck, alas.) It’s really hard to get cranking again once you’ve taken an extended timeout to triple-check a detail’s veracity.

BTW, Sinclair Lewis reportedly wrote 5,000 words a day, working precisely from 9-to-5. I find this highly implausible.

Jordan // Sep 7, 2011 at 10:35 am

Is it just me or is that “monster shark” a whale shark, one of the most harmless beasties in the sea?

Brendan I. Koerner // Sep 7, 2011 at 10:56 am

@Jordan: Indeed it is. Much easier to write quickly when you don’t give a damn about facts.