Pesky facts keep getting in the way of my book’s smooth narrative. Take the lovely paragraph I crafted yesterday, in which I argued that no one in the West believed that Cold War refugees could possibly flow toward the Soviet Bloc. An earlier experiment with such migration had ended tragically, after all, and that was before the total demonization of Communism had become a linchpin of American culture and politics.

But after a bit of reflection, I realized there were qualifiers to my blanket assertion. There were, indeed, cases of defections throughout the Cold War, some of which I’ve previously detailed in this space. I’m now committed to unearthing other instances in which Americans crossed the line into the Communist realm, despite the mountain of evidence attesting to the fact that such defections would inevitably result in misery.

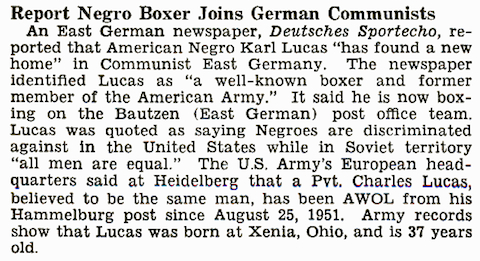

One of the first cases I came across in this quest was that of Charles Lucas, aka Karl Lucas, an American soldier who reinvented himself as an East German Everyman in the early 1950s. His story is told in-depth here, an account that includes this interesting tidbit culled from the Stasi’s secret files:

The Stasi agents appeared to be satisfied with Lucas’ behavior. Staff Sergeant Hübner of the Bautzen Stasi office reported “that in his political views, he is impressed by the successes of the GDR and actively supports its development.” In the clubhouse for foreigners and in public, he expressed “positive goals,” the report said. Cadre instructor Schmieger and cadre leader Kasper from the state-owned Bautzen Waggonbau railcar building company, where Lucas worked from April 1955 attested that he had “a positive attitude to our workers’ and farmers’ state as well as the Soviet Union.”

The Stasi also recruited him as an informant, mainly to observe the foreigners in the Clubhouse of International Solidarity and report on any escape plans, which Lucas dutifully did. On Oct. 5, 1955, he signed a handwritten note in English, stating that he was ready to support the Stasi “to safe the Peace of the World and the Safety from the Peoples in the D.D.R. and world. I know the Imperialist powers try to disturb the peaceful construction from the D.D.R.” [sic]. He was to sign his reports with the name Joe Baker.

You will be entirely unsurprised to learn that Lucas met with a bitter (and mysterious) end. An exile’s life is hard enough in the best of circumstances; when it is lived in a nation where the 3-cylinder Wartburg 1000 is considered the height of luxury, you’ve got serious problems.

scottstev // Oct 4, 2011 at 9:50 am

While you could find examples of practically every conceivable human behavior, are the number of wrong-way defectors high enough to be statistically significant? Always a fascinating story when it does occur: but that’s in-part due to the rarity and extraordinary circumstances of each case.

Brendan I. Koerner // Oct 4, 2011 at 9:55 am

@scottstev: That’s a great question. The simple answer is “no”–we’re talking maybe two dozen individuals all told, almost exclusively soldiers who made rash decisions. But I do have to consider whether these defections made any sort of impact on public perceptions–in other words, does my claim re: American perceptions of defection (i.e. that it only pointed in one direction) hold water?

Jordan // Oct 4, 2011 at 10:38 am

You’ve mentioned before some of the soldiers who crossed the DMZ into North Korea. Doesn’t sound like they had a whole lot of impact on America.

Brendan I. Koerner // Oct 4, 2011 at 11:04 am

@Jordan: Very true. Pretty motley bunch that made that move–young soldiers with emotional problems and total lack of foresight. IIRC, one of them said he thought the North Koreans would hand him over to the Soviets, who would in turn hand him back over to the Americans in some sort of elaborate prisoner exchange. He paid a terrible price for that harboring that delusion.