There is now a whole sub-genre of literature that deals exclusively with the lives of snipers. The public fascination with these lethal technicians is easy to understand: We see them almost as warrior monks, able to hush their thoughts so as to withstand the sheer boredom of their task. And there is something almost Zen about the way in which the consider their weapons as extensions of their physical bodies, and the rituals they carry out to reinforce that cyborgian mindset.

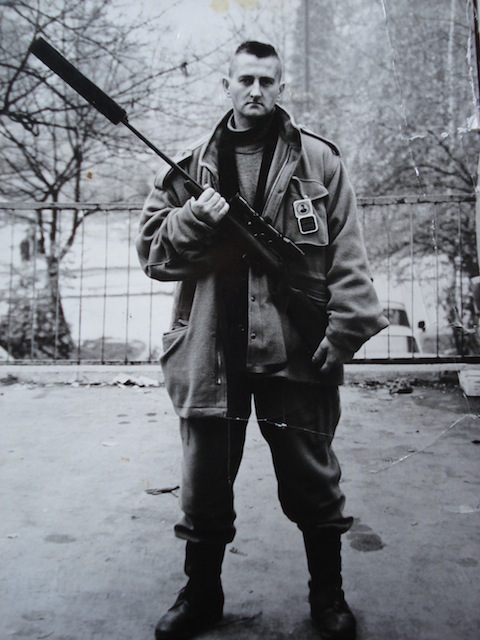

These themes are apparent in the work of the young Bosnian artist Adela Jusic, whose father (above) was killed while sniping in 1992. Jusic later discovered the diaries he kept throughout the Bosnian War, and used them to create her most well-known piece, “The Sniper.” She explains here the aura that surrounded her father’s work, and how it created a strange bond between father and daughter:

My visual, but also every other possible kind of memory of my father, are explicitly related to the war, the uniform, dirty boots, weapons, courage. He is primarily not father, but my father-soldier, who keeps coming and going, and every time he leaves, I am afraid he won’t be back. Those two identities of his were for me even more inseparable considering that I had been experiencing the happiest moments of our father-daughter relationship during those very moments of me cleaning his weapons. During these moments the father was proud of his daughter, and the daughter was aware of it, and this meant to her much more than any kind of hug or word.

Then he would leave to battle again, and he’d come back, and our family ritual would be repeated. By discussing this work with my close fellows who survived the war in Bosnia I realized that such a relationship with one’s father was not a distinct case, although I had long entertained such thoughts. On the contrary, this was a relationship quite common in the families of the time, dominated by the wartime family ritual which linked the father and the child in a completely unusual manner, in a way only war can link people and within any other relationship in the society. I’ve also noticed that the rituals of cleaning the rifle of one’s father-, and sometimes even one’s mother-soldier, are marked in the memories of those then-children, nowadays already mature people, as moments of intimacy and family idyll.

This is a theme that will soon come to light in American art, as the children of the last decade’s lost soldiers become old enough to shape and share their stories. There will be veneration, and there will be pain. And much of it will be anchored in scenes like the one described by Jusic, in which a child elbows into an adult ritual that gives them some small glimpse of the world their parent walked in.

captured shadow // Jun 4, 2012 at 3:11 pm

The Yugoslavia break-up may turn out to be a much more influential series of events than seemed possible for such a small geographical area. For instance a surprising number of former Yugoslavians went on to work in international NGO’s.

Having only shot a few rifles maybe I am overly impressed with snipers abilities. I think back to the three Somali pirates shot simultaneously. Amazing to me but maybe no big deal to a pro.

Brendan I. Koerner // Jun 4, 2012 at 3:21 pm

@captured shadow: The impressive part isn’t necessarily the marksmanship involved, but the preparation. Ninety-nine percent of a sniper’s job is quietly hiding until the perfect opening presents itself. I once read the obituary of an American sniper who spent three days laying facedown on a jungle floor in Vietnam, waiting for his assigned target to come into view. Amazing that he could just suddenly spring into action after such a long period of monotony.