When Senator Warren B. Rudman recently passed, I was struck by the concluding section of his New York Times obituary, which contained an anecdote that attested to his stubbornness:

When Senator Warren B. Rudman recently passed, I was struck by the concluding section of his New York Times obituary, which contained an anecdote that attested to his stubbornness:

Mr. Rudman feuded with his alma mater long after he had left its campus. In 1952, Syracuse University withheld his bachelor’s diploma because he had refused to pay an $18 fee for the yearbook, saying he had not been told of the charge in advance. After he was elected to the Senate, Syracuse offered him the degree or, if he preferred, an honorary degree. It eventually mailed him the diploma, but he never opened the package, and he later blocked an earmark of several million dollars for the university.

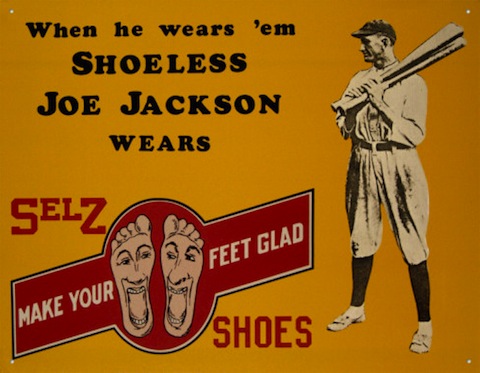

This story got me thinking about narratives in which tiny, even accidental slights can have life-altering repercussions down the line. A classic example from recent popular culture is probably Seasons Two of The Wire, in which a seemingly innocuous rivalry over stained-glass windows leads to a hard-working family’s total destruction. Yet I much prefer a tale from the realm of the real—the backstory on the whole Black Sox scandal as recounted by Shoeless Joe Jackson in this 1949 interview. According to Jackson, his lifetime banishment from the game was due solely to bad blood that existed between Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey and American League president Ban Johnson—bad blood that stemmed from a truly petty dispute:

I’ll tell you the story behind the whole thing. The trouble was in the front office. Ban Johnson, the president of the American League, had sworn he’d get even with Mr. Comiskey a few years before, and that was how he did it. It was all over some fish Mr. Comiskey had sent to Mr. Johnson from his Wisconsin hunting lodge back about 1917. Mr. Comiskey had caught two big trout and they were such beauties he sent them to Mr. Johnson. He packed the fish in ice and expressed them, but by the time they got to Chicago the ice had melted and the fish had spoiled. They smelled awful and Mr. Johnson always thought Mr. Comiskey had deliberately pulled a joke on him. He never would believe it any other way.

That fish incident was the cause of it all. When Mr. Johnson got a chance to get even with Mr. Comiskey, he did it. He was the man who ruled us ineligible. He was the man who caused the thing to go into the courts. He did everything he could against Mr. Comiskey.

There has to be some competitive advantage of being prone to grudges—they can be such a powerful motivator, perhaps even more so than the desire for creature comforts. But when a grudge is finally won after many years, even a lifetime of struggle, how often are the psychological rewards worth the accumulated bile?

Like gas stations in rural Texas after 10 pm, comments are closed.