March 1st, 2012

I’m genuinely surprised that this story, about the attempted assassination of a dissident Uzbek cleric, has remained so off-the-radar. The victim, Obidkhon Qori Nazarov, was reportedly shot multiple times—not in his native country, but rather in the small Swedish town of Strömsund. I can’t imagine the Swedes are too happy about a foreign nation’s assassins operating on its turf, which may explain why they’ve gone to such great lengths to keep the violent incident under wraps. Few details have yet emerged, for example, regarding the assassin’s modus operandi, though this United Nations dispatch claims that a discarded silencer was found near Nazarov’s wounded body.

I’m genuinely surprised that this story, about the attempted assassination of a dissident Uzbek cleric, has remained so off-the-radar. The victim, Obidkhon Qori Nazarov, was reportedly shot multiple times—not in his native country, but rather in the small Swedish town of Strömsund. I can’t imagine the Swedes are too happy about a foreign nation’s assassins operating on its turf, which may explain why they’ve gone to such great lengths to keep the violent incident under wraps. Few details have yet emerged, for example, regarding the assassin’s modus operandi, though this United Nations dispatch claims that a discarded silencer was found near Nazarov’s wounded body.

There will inevitably be debate over whether Nazarov deserved the protection he received, as he was suspected of orchestrating violent attacks against Western targets in Uzbekistan. But the larger issue has to be Uzbekistan’s tactics in its ongoing efforts to clamp down on Islamist opponents. Even the worthiest of political goals should be achieved with transparency and according to the rule of law. And that obviously ain’t what’s happening in Tashkent.

Related: Following the “two equals trend” rule of tabloid journalism, shall we say that Scandinavian countries aren’t too adept at keeping out foreign assassins?

Tags:assassination·Obidkhon Qori Nazarov·Sweden·Uzbekistan

February 28th, 2012

I’m a sucker for a tale in which the American legal system is asked to rule on the legitimacy of a medical treatment. No matter how dubious a quack’s product, he or she can always scrounge up satisfied customers to attest to its power, as well as a few expert witnesses who will say almost anything for a buck. There is thus great drama in watching judges and jurors grapple with this deluge of disinformation—there are few truer ways to assess the current state of our nation’s scientific literacy.

An all-time favorite is the 1946 trial of Dinshah Ghadiali, an oddball physician infamous for his marketing of Spectro-Chrome machines. Ghadiali swore that all manner of ailments could be cured through the application of multi-colored lights, and he convinced a fair number of gullible Americans to pay for his expensive placebo. As this 2005 account from Cabinet points out, Ghadiali had been acquitted at an earlier trial in Buffalo, thanks to the testimony of three venerable surgeons who claimed that Spectro-Chrome therapy was legit. The proceedings in 1946 might well have gone that way, too, if not for a single dramatic turn that undermined the defense in a major way:

Ghadiali called 112 satisfied Spectro-Chrome users in his defense (fifty-seven of whom merely suffered from constipation) and the trial lasted two months as a result. Some of them had become quite dependent on their machines—one woman claimed she patted and talked to hers. But Ghadiali’s case effectively crumbled when a patient he claimed to have cured of epilepsy with “tonations of Orange Systemic,” went into seizures on the stand, slumped to the floor, vomited, and swallowed his tongue. A real doctor rushed over to him and stopped him from choking to death by holding his tongue down with a pencil. “The jury was sent out and the court was recessed,” read the FDA’s notes on the trial, “Dinshah P. Ghadiali stood coldly by and neglected to offer Spectro-Chrome treatment.” After seven and a half hours’ deliberation, the jury returned to declare Ghadiali guilty. His dream of having a “SPECTRO-CHROME IN EVERY HOME” ended when he was given a three-year prison sentence and fined $20,000; all his promotional literature was ordered to be burnt, and further production of Spectro-Chromes outlawed.

To Ghadiali’s credit, though, he fought the good fight regarding the right of Atlantic City women to bare their knees.

Tags:Dinshah Ghadiali·gadgets·law·medicine·pseudoscience·Spectro-Chrome

February 24th, 2012

Just wanted to offer a quick bayarlalaa to y’all for sticking with this project over the past few weeks. Been hectic times here at Microkhan global headquarters, what with the book deadline looming and both the health-insurance and education systems conspiring to make the fam miserable. Better days ahead, for sure.

Tags:Ireland·Miami Showband·music

February 24th, 2012

I’m a sucker for creative metrics, such as measuring a creature’s ferocity by how quickly it can skeletonize a cow. One of my favorites is the way in which a nation’s development is assessed by how rapidly it’s being colonized by Western franchises. Take Indonesia, which is revealed here to be “opening a new convenience store every five to six hours.”

Yet the world’s biggest convenience-store chain, beloved nachos purveyor 7-11, has not found Indonesia to be the most welcoming of environments. Though its stores are now legion in Jakarta and elsewhere, 7-11 is on the defensive thanks to Indonesia’s penchant for genteel corruption:

After evaluating and issuing restrictions on minimarkets across the capital, the Jakarta administration has now set 7-Eleven convenience stores in its sights.

Following the issuance of a gubernatorial instruction specifically targeting 7-Elevens, Adi Ariantara, the head of the city’s economic bureau of the city administration, said the government would review the stores based on both the new instruction and a 2006 gubernatorial regulation on restaurants…

“We held an evaluation meeting on Sevel stores. We found that out of 57 in Jakarta, only 15 had proper licenses,” he said.

It was not clear why 7-Eleven was the only convenience store chain targeted by the new gubernatorial instruction. Adi said his office would review 7-Elevens based on a 2002 regional regulation that stipulated that modern markets up to 200 square meters in size should be located at least 500 meters from traditional markets. If they are between 200 and 1,000 square meters, they should be at least a kilometer away from such markets. Supermarkets and hypermarts must be at least two and a half kilometers from any traditional market.

According to data from the regional administration in 2011, Jakarta was home to 1,868 minimarkets. Of those, 1,443 of them did not have all the required permits, and some had none at all.

Okay, so let’s read between the lines here, shall we? Six years after a law is written, 7-11 becomes the only company to be threatened with store shutdowns—right as competition for customers is becoming most intense due to rising economic activity. Why do I get the feeling that 7-11 can only fix this problem through the liberal distribution of bribes?

Tags:7-11·corruption·economics·food·Indonesia

February 23rd, 2012

Back to the book today, after receiving some tragic news about one of the lead characters. Make do with some classic Joan Jett from the heyday of West German television. Back tomorrow about Indonesia’s raucous business climate.

Tags:Joan Jett·music·West Germany

February 22nd, 2012

I’m a few pages from the end of Kevin Myers’ Watching the Door, the peak of which is an extended discussion of how The Troubles became economically advantageous for both sides. I particularly enjoyed this dissection of how Belfast’s various paramilitary organization profited off the mayhem they created:

Glaziers—who, because they were associated with the building industry, tended to be Catholic—were in huge demand simply because of the bombings. Even a small explosion could break scores of windows; a large one simply hundreds. Bloody Friday, in all its extravagant generosity, had shattered many thousands of windows. The British government footed the bill for the damage, and there was barely any serious auditing of glazier bills. What government department counts broken windows?

Since glaziers were being made rich by the Troubles, the IRA thought it only right that it should get some of the vast amounts of government money pouring through their coffers, so it did. Glaziers paid the IRA (and in loyalist areas, by the same logic, the UVF or the UDA) protection. So, the British government was effectively subsidizing the Troubles; the more damage the terrorists did, the more money they would get‐and not just through glaziers, but through the entire building industry. As a matter of pride, the British government insisted on bombed buildings being reconstructed. Then they would be rebombed. Then rebuilt. Then rebombed…

A nice racket for the men with guns. And a good reason why they had so little incentive to negotiate an end to the violence.

(Image via Jez Coulson)

Tags:books·economics·Kevin Myers·Northern Ireland·The Troubles·Watching the Door

February 21st, 2012

Far be it from me to shed a tear for a murderous scoundrel whose various scams increased the price of everything in my adopted hometown. But did John Gotti get a raw deal when the Catholic Church denied him a funeral mass? A scholar makes the case here (PDF), arguing that the Church broke its own rules regarding how to deal with mafiosi:

Carlo Gambino was one of the more notorious mafia individuals in history, yet even he was able to receive the rite denied to Gotti. Gambino, who was the head of the New York mafia prior to [Paul] Castellano, was linked to dozens of “hits.” Nevertheless, when he died of a heart attack in 1976, still very active within organized crime, the Church raised no protest regarding his funeral…The Church also deemed Joseph Bonanno, known to some as “Joe Bananas,” deserving of a funeral Mass when he passed away of natural causes in May of 2002. Bonanno had been credited with being a creator of the American mafia and all evidence seems to point toward him being responsible for dozens of killings.

There is little doubt that Gotti was in a similar situation as Bonanno, both aware of his fate and having been removed from the criminal element for quite some time. The obvious difference between a Paul Castellano and a Carlo Gambino is not the way in which they lived their life, but how they died. Based on this “precedent,” it appears that the Church believes that a public death leads to “public scandal,” and accordingly, a funeral Mass should be denied. Naturally, after comparing Gotti with these other individuals, one is left with the impression that Gotti’s situation is similar to that of Gambino, Bonnano, and Dellacroce, rather than that of Castellano, De Cicco and the Spilotros. Based on this line of reasoning, it is asserted that John Gotti, having died in a hospital, in a very non-public manner, deserved full funeral rites.

The Church’s decision-making process was obviously affected by society’s changing attitudes toward organized crime, which were reflected in the way that Gotti was portrayed in popular culture. Who said the ecclesiastical hierarchy is totally incapable of sensing which way the wind blows?

Tags:Catholicism·crime·John Gotti·organized crime·religion

February 17th, 2012

Tough to believe I just recently stumbled upon this treasure trove of Roma-related information, which includes a bevy of rare photos and dozens of audio-enhanced oral histories. I came across the project while trying to get a better sense of what it’s like to endure aerial bombardment—more on that soon—but I ended up most absorbed in the accounts of Roma wedding practices. I was particularly drawn by what the interviewees had to say about the payment of dowries, a practice that strikes me as economically ruinous. Yet the Roma of Kosovo remain great defenders of the tradition, as illustrated by Hazbije Vičkolari’s pro-dowry argument:

Q: Would it be better to dispose of the dowry in the future?

HV: No- it’s better to ask for the dowry, because the groom didn’t work hard to raise and care for my daughter. I did that. To pay the dowry is much better because they (the bride’s family) have worked hard. You’ll sell your house to be able to marry your son. They’ll keep and respect the girl more; she’ll be part of their home. Again, though, if the bride does not obey them then the dowry should be returned.

As this interview makes clear, there has been a steady escalation in dowries over the years, despite the Roma community’s relative penury:

Q: Could you us about the wedding customs you followed?

ED: The customs are the same. The only difference is that our families didn’t have to spend a lot for the bride price, like today. In the past a bride cost only one or two horses.

All of this seems like it can lead nowhere good, as evidenced by the ill effects that dowries seem to have in other parts of the world. As I’ve discussed in this space before, there is an irresistible human impulse to one up each other in matters of honor—even if, in the end, the maintenance of that honor becomes wholly destructive.

Tags:dowries·economics·Kosovo·Roma

February 15th, 2012

Was just about to post about Roma wedding rituals when a health-insurance catastrophe struck. Can’t believe how hard they’re screwing us right now—jetting into town to see if I can fix anything through bribery and/or high-volume yelling. Back soon.

Tags:insurance

February 14th, 2012

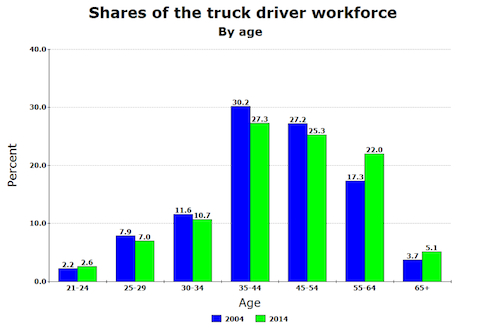

Based on my formative experiences with BJ and the Bear reruns, I’ve long imagined the archetypal American trucker as a picture of health. But the men and women who brings goods to market are actually a pretty grizzled lot these days (PDF):

The average age of a truck driver in the United States is over 48 years. Since 2000, the number of service and truck drivers 55 or older has surged 19%, to about 616,000, according to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics.

That age figure is particularly disturbing in light of the shorter-than-average life expectancies of truckers (also PDF):

Data on active OOIDA members who had died suggest that the average age of death for OOIDA members is only 55.7 years. While this sample is not random and is biased toward those actively in the work force and under special pressures encountered by owner-operators, at face value Mr. Siebert considered these numbers alarming. Using OOIDA member data, he reported that 49.5% of OOIDA members were obese, compared to only 31% of the overall U.S. population. Only 12.7% of OOIDA members were normal weight, compared to 36% of the overall U.S. population. Mr. Siebert also reported that 13 out of 430 recent OOIDA deaths (3%) were from suicide.

The question I’ve yet to see adequately addressed is why the truck-driving profession is having such a tough time attracting young blood. The most common explanation is that companies are reluctant to add payroll, and are thus driving their older employees into the ground, so to speak. But my hunch is that there’s something innate to the profession that doesn’t sit well with folks in their twenties. The sense of isolation, perhaps?

Tags:demographics·economics·trucking

February 10th, 2012

I’m sorely tempted to launch a whole new Microkhan series about the late-career floundering of high achievers. I’m just fascinated by this concept of how the truly great cope with the inevitable diminishment of their skills, as well as the revelation that they really should have taken better care of their personal affairs while riding high on the hog. Their most common tactic is to rage, rage, rage against the dying of the light, in increasingly undignified ways—until, at some point, they either spiral out of control or achieve some measure of peace. The journey to that denouement is a narrative arc that has been too seldom explored in modern storytelling. (Yes, yes, I know about The Wrestler. What else you got?)

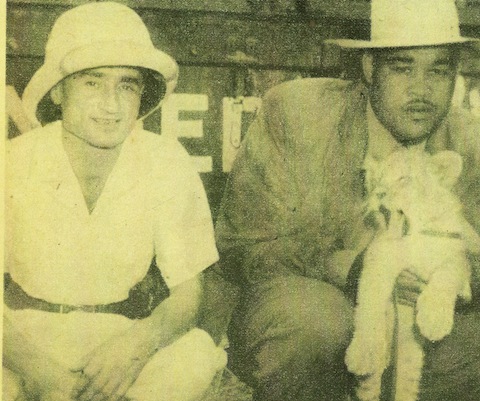

I’ll start with the tale of Joe Louis, circa 1950, when the former champ found himself deeply in debt and several steps slower than the latest generation of pugilists. That May, he abandoned his plans to recapture his heavyweight crown, choosing instead to join the Dailey Brothers Circus:

Under terms of the contract, Louis will receive a guarantee of $1,000 per day, with the total amount of the pact calling for $75,000, making Louis one of the highest priced features ever presented by a circus…

Louis will join the Dailey organization at Port Huron, Mich., May 23 and makes his first public appearance with the circus at Sarnia, Ont., May 24. The contract also provides that Louis be furnished with a private railroad car for himself and staff of five.

Strange that the article doesn’t describe what duties were expected of Louis. Did he simply stand in the center of the ring and accept the astonished applause of the circus’s audiences? Or was he compelled to show off a few boxing moves, to delight those without televisions who had only heard his fights on the radio?

Whatever the answer, I can see a great play growing out of this scenario. Act One, Scene One opens on Louis’s private railroad car as he crosses the border into Canada, preparing for his first circus appearance. What is going through his mind at that moment?

(Image via The Circus Blog, which I cannot recommend more highly)

Tags:boxing·circuses·Joe Louis·sports

February 8th, 2012

My tremendous thanks to everyone who turned out for last night’s live performance in Soho, at which I hopefully did a passable job of explaining Yuriy Sedykh’s physical genius. There was one technical hiccup for which I must apologize, though—the video of Sergey Litvinov, the Soviet Union’s golden boy of the hammer throw, cut out after a mere six seconds. As promised during my on-stage recovery from the mini-disaster, I’m posting the clip here for your perusal. The highlight is the masseuse’s expression.

Tags:hammer throw·sports

February 8th, 2012

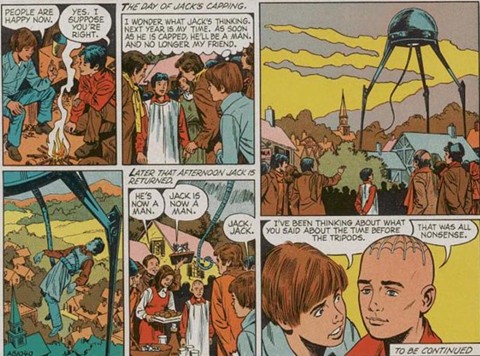

Saddened to hear of the passing of John Christopher, creator of one of my formative sci-fi experiences: the harrowing Tripods Trilogy. As I discussed nearly two years ago, Christopher’s tale of alien overlords was far more than crackling adventure yarn; it also centered on a powerful metaphor for parenthood that I admire to this day.

Check out the illustrated version of the trilogy’s first installment here. There are few better examples of young-adult fiction that nail the narrative trick of using a physical journey to symbolize an emotional journey.

Tags:books·comics·John Christopher·sci-fi·The Tripods Trilogy·writing

February 7th, 2012

If you have access to the New York City subway system, please consider coming down to Housing Works Bookstore Cafe this evening to check out Microkhan in the flesh. I’ll be performing as part of the revamped Adult Education lecture series, waxing poetic about a certain Soviet hammer thrower who has gotten much attention ’round these parts. I’ll be bringing along some vintage Soviet film clips to aid the storytelling, so please do come if you have a thing for Leningrad’s late ’70s funk scene.

Tags:hammer throw·Soviet Union·sports·Yuriy Sedykh

February 6th, 2012

Just slammed today, with both reporting for my Wired column and preparations for tomorrow’s performance in Soho. Leaving you with some classic Europop and some salient thoughts on creativity from the great Sean Price:

HipHopCanada: What starts your creative process?

Sean Price: The beat. The beat’ll tell me what to do. And sometimes I have moments where it’ll seem like writers block so I’ll just throw a word on the paper, like Botswana. Like my song “Figure 4.” I just wrote Botswana and then a whole bunch of shit came after that. I don’t know, there’s really no method to it, I just write. I don’t really believe in writer’s block, really.

Gonna try this the next time I get into a creative jam. My word will be “Papua.”

Tags:France Gall·music·Sean Price·writing

February 3rd, 2012

A big challenge I’ve faced with my book is the difficulty of grasping the rationales of truly eccentric characters. Even when I’ve been able to interview such folks, I rarely come away with a full understanding of why they made certain choices—their reasoning tends to be opaque, at least to a fairly normal bloke like me. Developing the empathy necessary to make their stories come alive thus requires a lot of focus and thought.

One way I’ve tried to overcome this obstacle is by boning up on the life stories of unusual individuals. I’ve lately been on a circus kick, which brought me in contact with the tales told by several knife thrower’s assistants. Perhaps my favorite such story is that of Ula the Painproof Rubber Girl, who tells her story here. This is the passage that really gets to the heart of why she does what she does:

I guess I’ve been aware of my own mortality from a very young age. There are so many things you can’t see coming. You can’t see death coming. You can’t see Mt. Vesuvius erupting. The probability of avoiding danger is higher with knives than against things that I can’t see or control here in New York City. The carpet could be pulled out from under you at any second and you’ll never see it coming, but I’ll see a knife coming if it’s going to hit me.

The way I read this, every knife that misses Ula by an inch represents a little triumph over her greatest fear. And the thrill of those tiny, regular conquests is what draws her to keep doing something that, by any rational standard, is completely foolish. Call it an addiction to denying death.

(Image via The Circus Blog)

Tags:circuses·knife throwing·philosophy·psychology·The Next Book

February 1st, 2012

Gonna spend this unusually warm Queens day tackling the book, having finally surfaced after a ten-day stretch of Wired work. I have roughly 648 hours before the first three-quarters of the first draft is due, so I’m feeling the heat. Enjoy a track culled from the latest installment of Fresh Produce, and see you back here tomorrow for a post about the lives of minor circus employees.

Tags:Megan Washington·music·The Bamboos

January 31st, 2012

The recent unpleasantness is Papua New Guinea provides a salient reminder that the global financial system, despite employing some very sharp minds, often acts on impulse. In response to the recent mutiny outside Port Moresby, Standard & Poor’s has slashed PNG’s credit rating. An S&P analyst explained the firms rational thusly:

We have these ratings under surveillance all the time, but we fully factor in, I mean the rating is B-plus, it factors in significant political risk already, but when we see mutinies of the type that we’ve been witnessing over the last few days, that is a true trigger for us that the levels of political risk are that much more higher than what we’ve been witnessing.

And so what did the analyst mean by “mutinies of this type”? As this piece points out, the revolt was by no means a mass movement:

Of the 200 troops [at the barracks], only about 30 were believed to have been involved in the mutiny, which began last Thursday under the leadership of Michael Somare’s appointee, Colonel Yawra Sasa.

Furthermore, those thirty mutineers were so half-hearted in their attempt that they readily swapped their guns for amnesty. As this insightful story points out, the mutiny was just a sideshow in a political clash that has been going on for months—a battle between Sir Michael Somare and Peter O’Neill over the prime minister’s office, a prize that will guarantee them awesome powers of patronage.

The mutiny will ultimately do nothing to alter PNG’s politics—it’s impact pales in comparison to, say, the December Supreme Court ruling that gave Somare some measure of legitimacy. But the foreign financial wizards who decide the country’s economic fate only pay attention when something sensational occurs—even if that something is totally inconsequential.

(Image via The Australian)

Tags:economics·Papua New Guinea·politics

January 30th, 2012

I recently finished up Bill Buford’s Among the Thugs, which is an absolute beast of a book. Aside from that great apocalyptic party scene in Bury St. Edmunds, there’s a terrific set piece in which Buford gets pummeled by Italian riot cops. I love the way he recounts his thought process while being savaged with batons—it makes me wonder whether only writers’ minds work this way:

All this was exceptionally painful, as would be expected, but my experience of it was different from that of the other who were being beaten up. Their experience was one of simple pain. For me, it was more complicated, because I knew that I would be writing about it. While being beaten up, I was thinking about what it was like being beaten up. I was trying to retain the details, knowing that I would need them later. I thought for instance that this experience was not so different from the one I had witnessed in Turin several years before when a Juventus fan, who had also surrendered, was beaten up by a number of Manchester United supporters. I thought of the fact that I could even think of this coincidence and marveled at the human mind’s capacity to accomodate so many different things at once. And I thought about that, the fact that, while being beaten up, I could think about the human mind’s capacity to accomodate so many different things at once. I thought about the expenses I had incurred and was grateful that I was going to get something out of this trip after all. But mainly I was thinking about the pain. It was unlike anything I had known and I wanted to remember it.

…and I wanted to remember it. Amazing to realize that an individual under such pressing physical duress could have such immediate perspective. But when your life is given over to telling stories, this is the default approach to every situation. There’s always a little voice chirping in your ear, “Imagine how this will sound on the page.”

Tags:Among the Thugs·Bill Buford·books·soccer·writing

January 27th, 2012

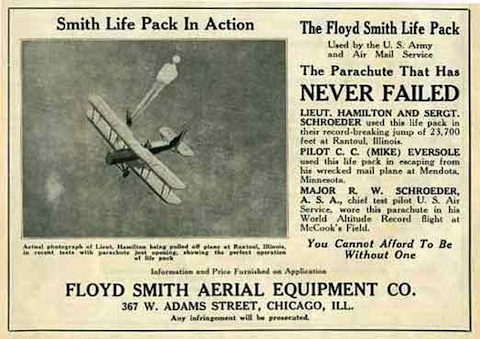

One of the book-related research tangents I’ve become ensnared in is the early history of parachuting. As you might suspect, the development of this important life-saving technology produced more than a few martyrs to the cause, as well as some heroes with complicated backstories. One of my favorite examples from the latter category is Carroll Eversole, an early airmail pilot who believed he could make a mint in the parachute development game. Like many inventors of that era, he saw nothing wrong with risking his neck to prove his technical savvy:

On February 18, 1921, Eversole was flying a dreaded twin de Havilland airplane from Minneapolis, Minnesota, when shortly after takeoff, and using a parachute, he bailed out of the airplane. A Chicago newspaper which wrote excitingly of this event, the first airmail pilot to survive a jump from a mail airplane, noted that the chute was “one of his own making.” Other witnesses remembered Eversole taking time to examine the parachute in detail before taking off. Officials investigated the crash and determined that Eversole had used the event to publicize the new parachutes, destroying an airmail airplane in the meantime. Eversole was quickly fired. His fellow pilots had mixed feelings about Eversole’s stunt. Few thought what he did was right, but none of them were sad to see a twin de Havilland airplane smashed into pieces.

Eversole had an alternate explanation for his post-jump dismissal: He claimed that he was fired for blowing the whistle on the drunkenness of U.S. Postal Service mechanics, whose incompetence led to the deaths of numerous airmail pilots. This excuse wasn’t enough to get his termination rescinded, but it did cause some USPS heads to roll.

What I’m missing is evidence that Eversole’s skydiving gamble ever paid off. Though his stunt was incredibly bold by modern standards, it was pretty much par for the course back in those days. More important, the market was flooded with worthy competitors; there is no single parachute design that trumps all others, given the personal preferences of pilots and the vagaries of aircraft. Based on the advertisement above, it seems that Eversole eventually ended up in some sort of business relationship with parachute manufacturer James Floyd Smith, a man known for his litigiousness. Here’s to hoping that Smith treated Eversole with the respect due a man who did something all-too-rare in modern capitalism: risk something more precious than borrowed money.

Tags:aviation·Carroll Eversole·parachutes·technology

January 26th, 2012

Getting thwacked by this Wired story I’m working on, which requires me to comprehend the nuances of both ribonucleic acid and artificial intelligence. Suffice to say, my brain’s full-up for the next twenty-four hours; see you back here shortly.

Tags:animation·M.A.S.K.·technology·TV·Wired

January 25th, 2012

The loyalest of y’all may have noticed that I have a longstanding fascination with the legal system’s efforts to value the supposedly invaluable. Which is why I was struck by this recent tidbit out of the Solomon Islands:

THE High Court has ordered the Solomon Islands Government and the Ministry of Fisheries to pay Marine Exports Limited more than $10 million for damages. This was in relation to the government’s banning of dolphin export in 2005.

The court granted the order for loss from dolphin feeds in the sum of $2,073,600, order for loss of property (38 dolphins) in the sum of $7,527,733.75 and the order for exemplary damages in the sum of $500,000. The order for loss of profit (loss from contract) in the sum of $4,785,600 and the order for interest to be included were refused.

If I’m reading this judgment correctly, then the court valued each dolphin’s life at roughly $29,318. (I tossed out the damages awards and converted from Solomon Islands dollars to American dollars.) I reckon that means a dolphin has about fifteen times more intrinsic value than a heifer, but only 1/200th the value of a human being (at least according to the U.S. government). I have to think that lopsided equation might have been dramatically altered if the dolphins had proven themselves more capable spies.

Tags:cetaceans·cows·dolphins·economics·intelligence·law·Solomon Islands

January 24th, 2012

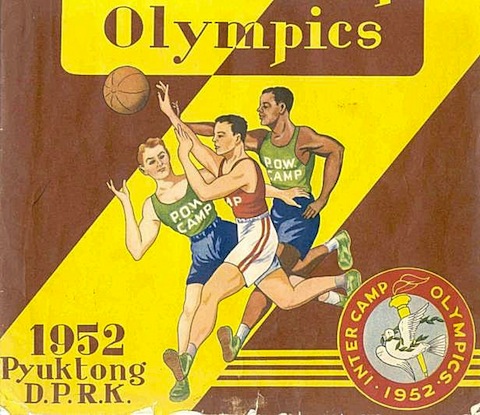

Given my attraction to tales about how folks cope with nasty twists of fate, I was bowled over to discover this rarest of Korean War artifacts: a program from the 1952 prisoner-of-war Olympics held at Pyoktong, North Korea. In addition to containing numerous photos of the sports contested—such as tug of war, football, and bizarre gymnastics, the booklet offers the thoughts of various participants. Their enthusiasm for the whole endeavor can either be construed as touching or deeply ominous:

It is a great honer for me to introduce you to this splendid book. Here, told in pictures, is the story of the greatest spectacle of our stay here in North Korea,the Inter- Camp Olympics of 1952. Each page servers as a guide that shall enable you to relive all the spine-tilling excitement of that truly marvelous athletic meet.

From the very moment the opening cerimonies began on November 15 until the closing of the meet on November 26 we witnessed splendid performances, thrills galore, great enthusiasm, sincere and wholehearted sportsmanship, and perfect goodwill among the many nationalities represented there….

Another very important factor in making this an unforgettable occasion was the attitude of the Korean People’s Army and the Chinese People’s Volunteers. Without their efforts such a tremendous undertaking could not have been possible, At all times the cooperation, generosity, enthusiasm, and selfless energy displayed by our captors was perfect and left absolutely nothing to be desired. The lenient treatment policy has long ago passes its title of lenient, it has instead become a brotherly love treatment for every one of us. The materials provided for the athletic meet, plus the grand array of expensive prizes and awards,were more than sufficent to prove the cincerity of the camp authorities of the Korean Peoples Army and the Chinese Peoples Volunteers in ensuring success of our first Inter-Camp Olympics

This book symbolizes the real will of all humanity to live in a spirt of brotherhood, in a world peace, free from fear, hatred, malace or antagonism. Here you can see vividly the harmonious atmosphere that pronailed at all times among men of various nationalities, races, creeds and colours.

So the question is, Should those who participated in these Olympics be condemned as collaborators, or hailed for keeping spirits aloft in the most trying of circumstances. A surprisingly even-handed discussion of that question can be found here.

And more photos of daily life in a Korean War POW camp here—with the caveat that the collection’s bounty of smiling faces tells only a stage-managed version of the truth.

Tags:football·Korean War·prisons·propaganda·sports

January 20th, 2012

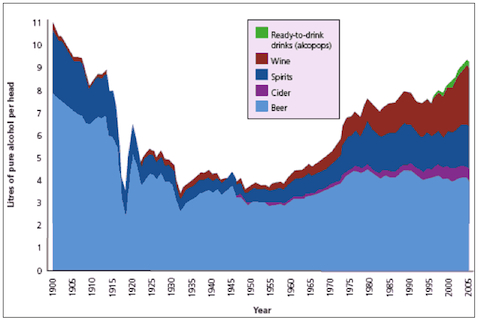

Though Europeans are generally drinking a great deal less these days, the Scottish are bucking the trend. Per the chart above, alcohol consumption has been steadily rising in the land north of the border established by the Treaty of York. The question that no one seems able to answer with any degree of certainty is why Scotland’s thirst for hooch cannot be quenched. The Scottish government evidently believes the conclusions made in this 2008 study, which lays a lot of the blame on the declining prices:

here is strong evidence from over 50 studies conducted in 15 European countries, America, Canada, New Zealand and elsewhere, that levels of alcohol consumption are closely linked to the retail price of alcoholic beverages. As alcohol becomes more affordable, consumption increases. As the relative price increases, consumption goes down. In Switzerland in 1999, a 30 to 50% reduction in taxation on foreign spirits, led to a 28.6% increase in consumption of spirits. There was no significant change in the consumption of wine or beer. In March 2004, Finland cut tax on alcohol (by one third) in an effort to reduce the level of cross-border shopping undertaken by Finns in other EU countries, particularly neighbouring Estonia, where the price of alcohol was much cheaper. Following the change, liver cirrhosis deaths were found to have risen by 30 per cent in just one year, as alcohol consumption increased by 10 per cent.

In Scotland, in real terms (taking into account disposable income), alcohol is 62% more affordable today than it was in 1980.

Scotland is trying to correct that problem with a new pricing law, which seeks to forbid discounts for buying alcohol in volume. But my hunch is that the only economic tactic that will truly work is the imposition of a minimum price per unit of alcohol. That would means the end of cheap fixes like The Purple Tin, which is basically the King Cobra of Scotland. If a unit of alcohol cannot be sold for any less than forty-five pence, many fewer will have the means to splurge on ten cans of high-alcohol lager. Which will hopefully mean a lot less of this.

A question, though: Has anyone studied what led to the decrease in Scottish alcohol consumption prior to the sharp WWI-related drop-off?

Tags:alcohol·beer·economics·Scotland

January 19th, 2012

Taking a day to plow through edits on Chapters Three and Four of the forthcoming book. Need to have the first 50,000 or so words to my editor by February 27th, so I’ll be ducking out on occasion to enter the hardcore writing bubble. Back tomorrow with a post about the dispiriting trend in Scottish alcohol consumption.

Tags:Scotland·soccer·sports

January 18th, 2012

By now you may have heard of the landmark federal conviction of Alfred Anaya, who played a key role in a drug trafficking ring that moved product from Mexico to the Midwest. What makes Anaya’s downfall so interesting is that fact that, by the government’s own admission, he never touched any drugs himself; his role was that of a master engineer, in charge of building secret compartments in the vehicles the operation used to transport its contraband.

The Feds have long been keen to bust men like Anaya, an effort complicated by the fact that there is no specific statute that bans the building of secret compartments. Anaya was tripped up by a series of wiretaps which revealed his knowledge of how the compartments would be used. Those wiretaps also hint at just how valuable Anaya’s services were to the organization:

Using wiretaps issued in another investigation, authorities intercepted calls involving known drug traffickers in which they discussed having hidden automobile compartments or “traps” built for them by defendant. References to detection by customs officials and the use of x-ray-interfering carbon paper and mirror-like surfaces provide evidence that the traps were intended for illegal drug-trafficking purposes. Other intercepted calls related to the possibility of defendant’s traveling to Mexico to fix a compartment that would not open.

In other words, Anaya’s skillset was so respected by his paymasters that they were willing to get him down to Mexico to open a single compartment, rather than hiring local talent to solve the problem. That’s a testament to the sophistication of Anaya’s work, and a clue as to why federal prosecutors considered him such a grand prize.

I plan on drilling deeper into the court documents to get a better sense of Anaya’s precise methods for creating world-beating traps. Amazing to me that something as simple as carbon paper could be so essential to foiling the zillion-dollar detection systems employed by Border Patrol agents.

Tags:Alfred Anaya·cars·crime·drugs·engineering·smuggling·technology

January 17th, 2012

I’m a few pages from the end of Bill Buford’s Among the Thugs, a study of Thatcher-era football hooliganism that doubles as a meditation on crowd dynamics. It’s perhaps best known for its opening set-piece, in which the author tags along with a bunch of Manchester United supporters on a depraved trip to Turin. But for me, the heart-and-soul of the book is the chapter set in Bury St. Edmunds, where Buford attends a disco sponsored by the racist National Front. In describing the terrifying late-night scene at a pub filled with skinheads, Buford does a masterful job of illustrating how one man’s idea of a crackling good time can be another man’s idea of absolute Hell:

Nick Griffin indicated that the volume should be turned up further, ad the music was now brutally loud. The room was hot and filled with smoke and smelled of dope. The air had grown heavy and damp. Sixty or seventy lads were in the middle of the room, clasped together, bouncing up and down, rubbing thir hands over each other’s heads and chanting in unison:

Two pints of lager and a packet of crisps.

Wogs out! White power!

Wogs out! White power!

Wogs out! White power!

They had taken off their shirt and were stripped to the waist, their suspenders dangling by their sides, knocking against their legs; sixty or seventy pale, narrow chests, covered in perspiration, pressed tightly together. They were bouncing so vigorously that they all fell over, tumbling on top of each other. I thought someone was hurt—a table had been knocked over—but they all clambered up over each other and, with difficulty, resumed their dancing. They fell over again, wet and hot. I don’t know if it was the drink or the drugs or the delirium of the dancing or that chorus, over and over again, but there was a menacing feeling in the air—sexual and dangerous. The people in the crush were not in control—the business of falling over was not intended and not one was finding it funny, as people might in the spirit of drunken merriment. Some of the lads appeared to be in a trance.

I can honestly think of no party that I’d like to attend less than this National Front disco. And given how the night ends, with his skull being bashed against a lampost by one of the intoxicated lads, I’m sure Buford is in no hurry to repeat the experience. Yet massive kudos to him not only for gaining access to this secretive world, but also for approaching it not with a sneer, but with an honest desire to understand how young men might be attracted to—or perhaps cajoled into liking—this belligerent form of fun. What he ends up reporting seems absolutely genuine, untinged by his personal abhorrence for the National Front’s odious politics. And yet that level-headed approach to the endeavor is what ultimately makes Buford’s account all the more affecting, and all the more damning.

Next up on the reading list, now that I’ve had my fill of horrific anecdotes from 1980s’ English soccer: The End of the Terraces.

Tags:Among the Thugs·Bill Buford·books·psychology·racism·soccer·sports·writing

January 13th, 2012

A moved-up book deadline has me scrambling over these next few days, so I’m just gonna ease you into the holiday weekend with some Uzbek pop. I don’t understand a word, of course, but my hunch is the ladies of Shahrizoda are preaching against the evils of materialism. The highlight is around the 1:08 mark, when the group briefly operates a kebab grill at what I take to be an Ürümqi bazaar. As an old girlfriend of mine once said, there is nothing sexier than a woman toiling over a steaming-hot griddle full of meat. (She had a summer job at Carney’s at the time, so her axiom was somewhat self-serving.)

Tags:music·Shahrizoda·Uzbekistan

January 11th, 2012

It’s a little hard for Americans to wrap their heads around alcoholism’s social toll in places like Mongolia, where the perpetually inebriated constitute a significant percentage of the potential workforce (and also commit the majority of crimes). So it will be interesting to see whether the government’s lead-by-example campaign makes any sort of impact on the problem:

It’s been a year since President Ts. Elbegdorj initiated the “Forward, to an Alcohol-Free Mongolia” campaign. On December 14, the Head of the Office of the President D. Battulga made a statement regarding the campaign’s accomplishments and effects during this period of time. Since the implementation of this alcohol-free idea, every event or ceremony involving the President should happen with no alcohol. The Alcohol Free Mongolia Association was formed, and so far the President has visited 10 provinces and made speeches concerning alcoholism and its negative impacts…

We clearly remember how the President welcomed the New Year with milk instead of champagne, and many people applauded and praised his action…Since April, every ceremony in the Wedding Palace has required the use of milk as the ceremonies are alcohol-free.

I have my doubts as to whether the average citizen will be inspired to give up drinking because their president abstains. The argument in favor of the program relies on evidence from a mid-1980s Soviet experiment, when Mikhail Gorbachev switched from vodka to orange juice at state functions. But the subsequent decline in alcohol consumption (since entirely reversed) probably had more to do with accompanying restrictions on access to drink than anything else. That sort of control was easy to accomplish in a nation with a state-run economy; in modern-day Mongolia, with its 91 distilleries, the road to relative sobriety will be much bumpier.

(Image via Mikel Aristregi)

Tags:alcohol·alcoholism·Mongolia·Soviet Union

January 10th, 2012

This memoir by the former bassist for Barbara Allen and the Tennessee Hot Pants includes a great vignette about playing Greenland’s Thule Air Force Base, where young men once scanned the skies for incoming Soviet ICBMs. Deprived of female companionship for months at a time, and surrounded by little but shiny white nothingness for most of the year, the base’s inhabitants made for less-than-inviting hosts when the Hot Pants showed up:

We were told that some of the service men there hadn’t seen a woman in over a year except for some of the entertainers who came and went. Therefore, each of us had to be assigned a body guard. The body guards were Danish civilians and traveled with us every place we went on the base. Trouble was, we needed more body guards to protect us from the body guards we already had. Those guys had, as the old saying goes, “Roman hands and Russian fingers”. My protector kept trying to get me to go off somewhere and have sex with him and I just laughed it off brushing away his hands at the same time.

Being in an all girl band was definitely a novelty. Each place we showed up the crowds were a bit rowdy and loud. However, that was nothing next to the reception we received when we opened our show in Thule Greenland. There were whistles, cat calls, applause, stomping, whooping and hollering. The stage was a large auditorium size and there was a space backstage for us to stay during our breaks. After our first set, I knew what that backstage area was for. What happened next came as a surprise. As soon as we stepped off that stage, hands came from all directions and my butt felt like I’d landed into a bed of lobsters. After escaping all the pinchers, I hurried back to the stage, body guard in tow, and ran behind the curtain. It wasn’t long before Barbara and the rest followed.

“What was that, a feeding frenzy?” I asked.

“Oh that happens to all women who come here.” the body guard answered in broken English.

Tales like these actually make me fear for our gender-imbalanced future.

Tags:Barbara Allen and the Tennessee Hot Pants·gender·Greenland·music

I’m genuinely surprised that this story, about the attempted assassination of a dissident Uzbek cleric, has remained so off-the-radar. The victim, Obidkhon Qori Nazarov, was reportedly shot multiple times—not in his native country, but rather in the small Swedish town of Strömsund. I can’t imagine the Swedes are too happy about a foreign nation’s assassins operating on its turf, which may explain why they’ve gone to such great lengths to keep the violent incident under wraps. Few details have yet emerged, for example, regarding the assassin’s modus operandi, though this United Nations dispatch claims that a discarded silencer was found near Nazarov’s wounded body.

I’m genuinely surprised that this story, about the attempted assassination of a dissident Uzbek cleric, has remained so off-the-radar. The victim, Obidkhon Qori Nazarov, was reportedly shot multiple times—not in his native country, but rather in the small Swedish town of Strömsund. I can’t imagine the Swedes are too happy about a foreign nation’s assassins operating on its turf, which may explain why they’ve gone to such great lengths to keep the violent incident under wraps. Few details have yet emerged, for example, regarding the assassin’s modus operandi, though this United Nations dispatch claims that a discarded silencer was found near Nazarov’s wounded body.