Big writing day—if I don’t get this chapter out the door by Sunday morning, the whole house of cards may come tumbling down. Back tomorrow with something choice.

The Next Thousand

September 28th, 2011

Comments Off on The Next ThousandTags:Dee Edwards·music·R&B

For Research Purposes Only, Of Course

September 27th, 2011

When President Richard Nixon visited China in 1972, his hosts treated him to a performance of The Red Detachment of Women, a “revolutionary ballet” in which girls with guns dance en pointe to music about the evil of landlords. When Nixon expressed his admiration for the production to Madame Mao, she replied with a ready-made quip: What the president had just seen was not the work of a single individual, but rather the art of the masses.

Because they represented the triumph of collective action, entertainments like The Red Detachment of Women were supposed to eliminate the need for cultural imports, which might threaten to spread decadent ideas. Indeed, virtually all Western movies and music were banned under Mao’s regime—at least for the little people. As revealed in this lengthy discussion of Maoist film, the elite rather enjoyed checking out the cultural artifacts they were happy to declare verboten for the masses—though they were not quite honest enough to admit their reasons for doing so:

There were so-called “internal” (neibu) screenings of banned works and foreign works that were not released to the general public. In theory, these were to inform trusted central figures of what to be on guard against. But tickets to internal screenings were highly sought after, and not always for those reasons. I believe that Madame Mao (Jiang Qing) was a huge fan of The Sound of Music.

If a mere peasant or shopkeeper were caught watching a Julie Andrews film, I very much doubt he could escape punishment by claiming he was simply boning up on what to avoid.

More from The Red Detachment of Women here. I’d love to see a sequel to Black Swan that centers on Mila Kunis’s efforts to depict Wu Qinghua.

→ 2 CommentsTags:ballet·China·Communism·dictatorship·Mao Zedong·propaganda·The Red Detachment of Women

Primal Joy

September 26th, 2011

Recovering from the flu today, so don’t quite have the mental fortitude to do anything more complex than shuffle from coffee pot to couch. But thought I’d muster the energy to share the clip above, the first goal from last week’s Fenerbahce-versus-Manisaspor soccer match in Istanbul. For those of y’all who don’t follow Turkish sports, it seems there was a bit of violent unpleasantness at Fenerbahce’s last home game, and club officials were seriously considering holding the Manisaspor tilt in an empty stadium as punishment for its hooligans. But they decided instead to admit only women and children younger than 12, which resulted in a fan dynamic that’s guaranteed to put a lump in your throat. Don’t think I’ve ever heard a post-goal celebration quite that high-pitched. But it works.

Take note, though: At the 2:23 mark, there are definitely a couple of older dudes in the crowd. Wonder if they had to don wigs to sneak in, in sort of a reverse Offside maneuver.

A Rare and Monstrous Talent

September 23rd, 2011

I’m the early stages of planning a new Wired project, one that will delve into the economics of how to properly compensate “ultra-specialists”—that is, people who possess the unusual ability to tackle extremely arcane tasks. I guess the classic example here would be those left-handed relief pitchers who make millions by appearing in a handful of innings each year. Or programmers who are fluent in outmoded languages, and so need to be paid handsomely to fix snafus in legacy systems that still underpin critical infrastructure.

A great character of yore who made a mint off a strange talent was the man born Saverio Giannone, better known to fans of pugilistic history as Joe Grim. By his own admission, Grim had no fighting skills to speak off—he could barely hit hard enough to break a piece of tissue paper, and his open stance and slow feet made him easy to strike. Yet like Homer Simpson, Grim had an amazing knack for absorbing the worst physical punishment imaginable—his claim to fame was that you simply couldn’t knock him out. This great history of Grim’s bizarre, loss-filled career includes a fantastic tidbit regarding the man’s 1905 run-in with then-rising heavyweight star Jack Johnson:

Even though Johnson weighed 210 to only 165 for Grim, there were still doubts he could put the human punching bag away. Confident of his punch, Johnson had wagered heavily that he’d knock the man out.

Some 3000 people, including Nat Fleischer, future founder of The Ring, paid to see the match in Philadelphia and it would be even money on which fighter was the main draw. In the first three rounds Grim was beaten around the ring. He would drop and the crowd would shout, “Get up Joe!” and Joe would get up, a broad grin on his bloodied face. In the fourth Johnson landed a punch that dropped his opponent to the floor with a thud. Grim waited on hands and knees as the referee counted, then jumped up before the count of “ten”. Three more times he went down in the round, three more times he got up. The forth round followed suit, and in his corner, an amazed Jack Johnson declared, “He ain’t human.”

In the fifth Grim was down six times, three times for a count of eight and three times for a count of nine. Each time he rolled to his belly, climbed to his knees, and waited for the referee to “almost” count him out before rising amid the cheers of the crowd. It wasn’t boxing, it was a circus act with the lion tamer letting the lions do their worst, then leaving the cage savaged and bloody to take his bows.

The sixth and final round saw a desperate Johnson trying to win his bets. Jack caught Grim with a right to the chin so hard, as Nat Fleischer said, “. it caused Grim to turn a complete somersault.” The referee counted as Grim lay there senseless, some thought dead. It appeared he wouldn’t beat the count, but on eight the bell rang, ending the fight and saving Grim from his first knockout. He had been knocked down eighteen times by one of the hardest punchers of his time but he hadn’t been counted out. In Grim’s mind, the defeat was a victory of the only sort he would ever know. More fights followed and the Iron Man didn’t disappoint the fans of that cruder era. He didn’t win, but he didn’t fail to shout out after the final bell, “I’m Joe Grim! Nobody knocks out Joe Grim!”

Popular lore holds that Grim never actually won a fight, but his thorough BoxRec entry suggests that he tasted the thrill of victory on roughly five occasions—versus 33 losses. How long the sweet memories of triumph existed in his mind is anyone’s guess; my hunch is that Grim’s mental faculties did not fare well in his post-career years, given the trauma his brain endured in the ring.

(Image via Antiquities of the Prize Ring)

Pushing the Revolving Door

September 20th, 2011

I can’t say I’m a huge fan of The Shawshank Redemption, but there’s one scene toward the end that I consider truly memorable. It’s the one in which Morgan Freeman, having been paroled from prison after so many years behind bars, is shown at his job in the free world: bagging groceries at a supermarket. Upon feeling Nature’s call, Freeman waves a hand at his manager and asks for permission to use the restroom. Slightly embarrassed by the fact that this request was made public, the manager calls Freeman over and informs him that he’s free to go and hit the head whenever he pleases.

This gentle reprimand hits Freeman hard—it’s the moment he realizes that his decades of incarceration have left him so thoroughly institutionalized that he cannot function in normal society. It’s a bitter revelation that I immediately thought of upon reading the tale of Craig Andrew Glen Blair, a career criminal in New Zealand who seems to have decided that he lacks the skills to exist beyond prison walls:

Blair had only been out of prison from a previous bank robbery offence for five days when he decided he could not cope living on the outside.

He had spent all his money on release on alcohol and had lost contact with his immediate family, his lawyer Tim Barclay told the Rotorua District Court.

Blair, 43 made a calculated decision to reoffend just enough to be able to be sent back to jail, he said.

Blair, who had already served a two-and-a-half year sentence for robbing the National Bank in Te Puke in 2008, held up the Westpac Bank in Rotorua in June this year.

He waited in the queue and then approached the teller demanding money, saying he had a gun in his bag. After being handed a “modest” $1140, Blair walked 400 metres to the Rotorua Police Station to give himself up.

At sentencing yesterday Judge Phillip Cooper said Blair had refused any rehabilitative assistance available to him on his release. He also made no attempt to contact his immediate family, which included his adult children, for help.

Prison seems like such a ghastly place to most, so it’s very difficult to understand Blair’s mindset. Yet at the same time, his seemingly odd choice dovetails with fresh research (PDF) questioning whether incarceration really reduces recidivism. The fact of the matter is that humanity’s various systems of justice are all united by our faith in the hierarchy of punishments. But what happens when the facts of life on the outside invert a critical part of that hierarchy—that which holds that prison is a worse fate than supervision in the free world?

Comments Off on Pushing the Revolving DoorTags:law·New Zealand·prisons·psychology

Where Do We Go Now?

September 16th, 2011

Given how much I write about Papua New Guinea, it would be much to my discredit if I didn’t wish the nation a happy 36th birthday before I split for the weekend. Here’s to hoping that things start looking up for the country in the post-Michael Somare era; as newly minted prime minister Peter O’Neill noted today with exceptional frankness, there is much progress to be made:

“As a nation we have come a long way in 36 years, but our record is one we cannot be very proud of…Regardless of where you are, look around you. Our infrastructure, like roads and bridges, airports and wharves are in a shamble. We have fallen short of our national goals and principles enshrined in our constitution.”

You know what they say: the first step is admitting that you have a problem.

Comments Off on Where Do We Go Now?Tags:Papua New Guinea

The Eyeball Test

September 16th, 2011

I had to do a double-take this morning when I saw that The New York Times had a (digital) front-page feature on the Freedmen controversy. The question of whether Black Indians deserve tribal membership is something I wrote about six years ago, in a mammoth Wired piece that pondered the role of genetic analysis in this debate. One of the historic details I included in that story is worth noting in light of the Cherokee Nation’s claims that the Freedmen aren’t really Indian. It concerns the Dawes Roll, the 1906 census of Oklahoma Indians that the tribes claim is the only acceptable way to document Native American heritage:

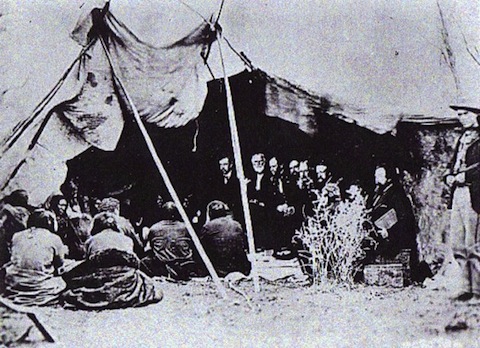

The Dawes Roll was the brainchild of a patrician Massachusetts senator, Henry Laurens Dawes, who wanted to “civilize” Indian territory by ending communal land ownership and allotting 160-acre plots to individual members of each tribe. At first, the tribes resisted the white man’s efforts to destroy a centuries-old way of life. One Creek official compared the Dawes Commission, which oversaw the roll’s creation, to the plague of locusts the Egyptians faced in the Bible. But the tribes relented, if only to avoid a conflict with the US government.

The task of enrolling the Indians was assigned to white clerks dispatched from Washington. They set up vast tent villages in Oklahoma towns and sent word through tribal officials that anyone interested in claiming their land had to register. Once the news spread, the tents were deluged with applicants, including scores of Caucasians claiming to have a sliver of Indian blood. More surprising for the clerks were the thousands of African-Americans who showed up. The 1890 census counted 18,636 people “of Negro descent in the Five Tribes.” With no ability to speak any Native American language, the clerks often relied on the eyeball test. Those who fit the stereotype – ruddy skin, straight hair, high cheekbones – were placed on the “blood roll.” The roll noted each person’s “blood quantum,” the fraction of their parentage that was ostensibly Native American. That number was sometimes based on documentation, but often, given the lack of accurate records and the language barrier, it was nothing more than crude guesswork.

Those with obvious African roots were sent to a different set of tents. There, they were added to the Freedmen Roll, which had no listing of blood quantum. Contemporary Freedmen believe the segregation was part of a government conspiracy to steal Indian land. Freedmen, unlike their peers on the blood roll, were permitted to sell their land without clearing the transaction through the Indian Bureau. That made the poorly educated Freedmen easy marks for white settlers migrating from the Deep South. Stories abound of Freedmen, unable to read the contracts they were signing, selling their 160-acre plots for as little as $15.

The haphazard nature of the Dawes clerks’ methodology means that there are Freedmen who, at a genetic level, can probably claim to possess more Native American DNA than enrolled tribal members—a fact that gives lie to the Cherokee argument that their stance is meant to preserve a coherent Indian racial identity.

The attendant issues of memory, sovereignty, and meaning are far too complex to unpack in this limited space. But as long as the Cherokees and other tribes insist on clinging to a biological myth perpetuated by early 20th-century bureaucrats, it’s going to be hard to take their other concerns seriously. Besides, hasn’t history repeatedly shown that nations only prosper when they expand their notion of citizenship beyond mere ethnic affiliation?

→ 1 CommentTags:Cherokees·Dawes Act·Freedmen·Native Americans·racism·Wired

Tommy Can You Hear Me?

September 15th, 2011

Knocking back a few pints with fellow scribe Doug Merlino last night, the conversation inevitably turned to sports—or, more specifically, the late 1980s heyday of Sports Illustrated, the magazine that taught us both to love the art of storytelling. We both remembered that this vintage era of SI featured a ginormous number of “as told to” yarns, in which troubled athletes relayed their tales of woe through the magazine’s best writers. Perhaps the most classic example is Gary McLain’s famous mea culpa about his cocaine use, a piece that probably did more to convince me of the drug’s wickedness than 10,000 “Just Say No” spots. (FYI, McLain seems to have landed on his feet in the years since.)

Knocking back a few pints with fellow scribe Doug Merlino last night, the conversation inevitably turned to sports—or, more specifically, the late 1980s heyday of Sports Illustrated, the magazine that taught us both to love the art of storytelling. We both remembered that this vintage era of SI featured a ginormous number of “as told to” yarns, in which troubled athletes relayed their tales of woe through the magazine’s best writers. Perhaps the most classic example is Gary McLain’s famous mea culpa about his cocaine use, a piece that probably did more to convince me of the drug’s wickedness than 10,000 “Just Say No” spots. (FYI, McLain seems to have landed on his feet in the years since.)

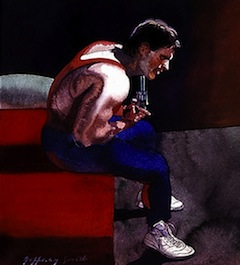

The anti-drug story that occupies an even more prominent place in my memory banks, though, is the 1988 tale of Tommy Chaikin, a South Carolina football player who essentially lost his mind to steroids. The opener is a classic—a well-crafted shocker that still makes you believe that you’re reading Chaikin’s thoughts, not those of his co-writer:

I was sitting in my room at the roost, the athletic dorm at the University of South Carolina, with the barrel of a loaded .357 Magnum pressed under my chin. A .357 is a man’s gun, and I knew what it would do to me. My finger twitched on the trigger.

I was in bad shape, very bad shape. From the steroids. It had all come down from the steroids, the crap I’d taken to get big and strong and aggressive so I could play this game that I love.

I felt as though I were sitting next to my body, watching myself, and yet I was in my body, too. I was trying to get up that final bit of courage to end it all. Every nerve inside me was on fire. My mind was racing. I couldn’t get a grip on anything. The anxiety attacks I’d been having for the last five months had become so intense that I couldn’t stand them anymore. I’d lost control of everything—it’s impossible to describe the horror I felt, the fear, the anxiety over that loss of control.

I could hear my teammates outside my room. They were walking back and forth, listening at the door. They talked in low voices, and they sounded very concerned. Every now and then someone would try opening the door, but I’d locked it.

“Tommy,” someone would say quietly. “You O.K.?”

However, the image that’s really stuck with me all these years is not Chaikin with a gun beneath his chin, but rather the face of the poor delivery boy who had to endure the narrator’s drug-fueled thuggery:

One night in my dorm room, I pulled a shotgun on the pizza delivery boy, threw him down and put the gun in his face. It was loaded and I could have blown the kid all over the floor, but I was just fooling around. It was the kind of thing I thought was funny.

Even as a lad, I thought to myself, “Wait, the delivery boy didn’t report that to the cops?” I’ve been suspicious of the scene every since, but I have to admit that it does seem highly plausible. I wouldn’t put it past the Columbia police department to look the other way for the sake of Gamecocks football.

(Image via master illustrator Jeffrey Smith; check out his gallery of sports illustrations here.)

→ 2 CommentsTags:drugs·football·sports·Sports Illustrated·steroids·Tommy Chaikin·writing

Everything’s Better with Disco

September 14th, 2011

Invoking khan’s prerogative to steal a day for book writing. Because if I don’t finish this chapter by week’s end, I fear the worst for the family’s future over the long winter. Even in Queens, keeping a yurt heated ain’t cheap.

Comments Off on Everything’s Better with DiscoTags:disco·East Germany·music·propaganda

Fear the Beard

September 13th, 2011

One of the many historical realms I’m trying to bring to life in the next book is that of Oregon’s Vietnam-era college scene. And one of that scene’s biggest controversies was that involving Fred Milton, an Oregon State University football star who refused his coach’s demand that he shave his beard—in the off-season, it’s important to note. When Milton’s stance led to his dismissal from the team, the school’s Black Students Union called for a university-wide boycott until he was reinstated. Yet only a small fraction of Oregon State’s 14,000 students heeded this request. And so every single black student on campus—all 47 of them—left school to protest Milton’s treatment, causing a tremendous stir.

The controversy caught my eye not only because it seems so archaic by today’s permissive fashion standards—imagine if Milton had shown up with this—but also because it highlights a divide that reveals the deep-seated fears of Coach Dee Andros’ generation. To him, Milton’s refusal to toe the grooming line represented a breakdown in social order on par with the distribution of Trotskyite propaganda to kindergartners—the beard was not just a fashion choice, but a tangible symbol of the next generation’s resistance to authority:

The strongest formal opposition to Andros came from the 88-member faculty senate. A newly formed Committee on Minority Affairs said the university could not justify disparaging an “individual student’s right to determine what constitutes proper social and cultural values,” especially as they pertain to mode of dress and style of hair. Later the faculty “lost its nerve on this one,” says Andros. “The way the resolution stood, they were giving the hippies license to walk naked at graduation.”

Andros also said the faculty had missed the point. “I’m not just fighting hair on the face,” he said. “I’m fighting for a principle of education—the right to run my department. If I thought it would end with a beard or a mustache, I wouldn’t be so bullheaded. But if they beat you on one issue, they’ll keep right on.” He said he also had a duty to the coaching profession, that he couldn’t “abandon the concepts of training, discipline, team unity and morale.” He spoke of the lessons to be learned in the “willingness” of an individual to subordinate himself to a cause greater than himself. He said this might not sound very democratic but he wasn’t trying to run a democracy, he was trying to run an athletic program.

I can’t help but think that the Milton-versus-Andros beard spat neatly summarized a lot of the political tumult that was to come over the ensuing decades—I’ve always thought that the simplest, most honest way to characterize the ongoing ideological divide is as hippies versus squares.

This particular story’s resolution was long and painful, with Milton ending up at Utah State and the Coach Andros cowed into rescinding his ban by Oregon State’s administration. The silver lining, though, is that Andros and Milton reconciled a few years later, with the coach helping his former star get a gig in the Canadian Football League, a place with a rich history of tolerating fantastic beards.

→ 3 CommentsTags:education·football·Fred Milton·Oregon·politics·racism

Demo or Die

September 12th, 2011

Let me start the week by directing y’all’s attention to my latest Wired essay, in which I argue for the revival of a bygone regulation: the requirement that patent applicants submit working models of their inventions. Sound onerous? Yeah, that’s the point:

The abolition of the model requirement [in 1880] was initially a boon to backyard inventors, who often lacked the capital to build detailed mock-ups of their visions. But as America’s population of skilled engineers has exploded, the patent system’s low barrier to entry has become its fatal flaw. The USPTO received 520,277 applications in 2010, a figure up nearly 500 percent since 1970. Countless inventions of dubious value or debatable novelty slip through this overwhelmed system, leading to endless litigation that has become a serious drag on American industry. “The requirements to patent have become, in my humble view, a joke,” says Mario Biagioli, a history-of-science professor at Harvard University.

The USPTO could instantly slash the number of applications by compelling inventors to submit working models whenever feasible. The most abstract inventions would be exempt, of course, but these constitute a small minority of applications; business models, for example, made up about 2 percent of the patents issued last year, and drug compositions were roughly 3 percent. The bulk of inventors would have to come up with three-dimensional examples of how their creations would look and function. Have a great idea for a longer-lasting semiconductor? A sturdier toxic-waste container? A safer lawn dart? Don’t just submit a diagram; make a model the examiner can touch.

The idea for this essay grew out of a dialogue started by my boss Chris Anderson, who posited that the tech industry ascribes too much value to mere ideas. Without the organizational chops to realize that vision, he argued, an idea is a trifling thing. That contention got me thinking about readjusting the patent system in order to reward a skillset beyond mere creativity. Re-establishing the model requirement would compel inventors to prove that they can work well with others, which is the real key to translating ideas into tangible goods.

It’s a notion that certainly doesn’t gibe with our vision of the lone inventor making magic in his garage. But that was always just an illusion—what, you think Thomas Edison worked alone?

→ 2 CommentsTags:innovation·intellectual property·patent models·patents·technology·Wired

The Ponchos: A PG-13 Masterpiece

September 9th, 2011

I can probably count on two hands the number of movies I’ve paid to see twice in a movie theater. Virtually all are classics that I’ve caught as revivals: The Godfather II, A Clockwork Orange, and The Bridge on the River Kwai immediately pop to mind. But there is also a decided oddball in the mix, a movie that no one in their right mind would consider worthy of being mentioned in the same breath as the works of Kubrick and Lean: the 1987 teen comedy Can’t Buy Me Love, a flick that is mostly memorable for its odious plot.

For those too young to remember the twilight of Ronald Reagan’s second term, Can’t Buy Me Love was the tale of a high-school outcast who paid a mega-popular cheerleader to date him for a week, as a way of climbing the local social ladder. The fundamental lesson of the movie is that a pretty girl will chastely whore out her affections in exchange for several hundred bucks, provided she’s desperate enough or cash. An ugly moral, but one my grade-school self wasn’t nearly smart enough to understand. I was just thrilled to be watching a flick that was rated PG-13—it made me feel mature beyond my years. And so my pal and I ended up catching the movie twice, after getting dropped off at the multiplex by his extremely permissive dad. For two kids who were just beginning to figure out that girls were not, in fact, the enemy, Can’t Buy Me Love was the closest we could get to an illicit thrill.

I remember little about the movie today, save for the line uttered above by Patty, the stereotypical class tramp. Finding herself alone in a car with the protagonist, now considered quite the catch after his fake dalliance with Miss Cheerleader, she makes her move by uttering a line demands recognition with a Poncho, Microkhan’s award for memorably uttered lines by supporting characters. For those of you who can’t safely YouTube right now, the decidedly PG-13 sentence is as follows:

I happen to know in the whole school, there’s only one other titty quite this pretty.

It wasn’t the naughtiness of the line that struck my grade-school self; it was the fantastic delivery by actress Darcy DeMoss, who raises her voice to a geisha-like lilt as she hits the word “quite.” Then there’s the way she touches her fingertip to the corner of her mouth, suggesting depths of lewdness that no PG-13 movie could possibly explore.

Pure theatrical genius—a masterclass in playing the floozy in her prime. I highly recommend that all actress asked to play women of loose morals study DeMoss’s performance in the same way that aspiring military commanders study Võ Nguyên Giáp‘s tactics at Dien Bien Phu.

→ 4 CommentsTags:Can't Buy Me Love·Darcy DeMoss·movies·The Ponchos

With Friends Like These

September 8th, 2011

As Muammar Qaddafi continues to rage, rage, rage against the inevitable dying of the light, the time has come to assess just how much damage he wrought during his absurdly long rule. I never cease to be amazed by the man’s longevity; just recently, in fact, his name came up in my book research, as a man who was said to extend offers of hospitality to American fugitives. He briefly flirted with the idea of turning Tripoli into a North African version of Havana, a base of operations for on-the-lam radicals whose ability to escape justice might prove deeply embarrassing for the United States. But like many a megalomaniacal strongman, Qaddafi had an incredibly short attention span. Before he could set the wheels in motion on his anti-American plan, he moved on to another pet project: aiding the Irish Republican Army in its fight against the British.

Ultimately, this sort of half-baked approach to policy will be Qaddafi’s legacy. The man was big on concepts—albeit dastardly concepts—but laughably awful at follow-through. Uganda knows this well, based on Qaddafi’s lame attempt to prevent his pal Idi Amin’s overthrow in 1979. Libya sent plenty of troops to Uganda, to stave off a Tanzanian force bent on ridding its neighbor of Big Daddy’s murderous influence. But no one seemed to make any plans beyond simply loading the soldiers onto a Kampala-bound plane—which is why the bodes of so many Libyans now fill mass graves in Uganda:

The arrival of the Libyan desert commandos was as surprising as it was annoying because we had made it all along clear to Amin and the entire Army top brass that all we needed was artillery fire power to neutralise the enemy’s Katyusha and not the personnel. Communication was the biggest problem. They could neither communicate in English nor Swahili. Attempts to use Nubian which is more like broken Arabic hit a dead end because they could not understand the dialect. We resorted to communicating by hand.

“Another problem was in the dressing and the arms that the Libyan commandos opted to use. Their clothes were clearly not for jungle warfare. Instead of arming themselves with assault rifles like G3s and AK47s, they had light arms like Uzi guns and a wide range of machine pistols. We did not have any way of informing them that their clothes and arms were going to work against them, so we simply let them go to the front. They joined our forces that were waiting for the enemy in Kalisizo. The enemy descended upon the area in full force. The battle was hot for both our troops and the Libyans, who suffered because of their failure to comprehend withdrawal orders issued in Swahili.

The following morning when some of them came back to Masaka after the fall of Kalisizo, they were a sad sight. Some were dead and many of them were injured. It was a pitiful scene watching those who were lucky to escape without any injuries tearfully carrying their wounded and dead colleagues off their small trucks.

History does not seem to have recorded Qaddafi’s reaction to this slaughter. My guess is that by the time the news reached his ears, he had more-or-less forgotten that he’d ordered the mission in the first place.

→ 4 CommentsTags:dictatorship·Idi Amin·Libya·military·Qaddafi·Uganda

An Appeal to the Rain Gods

September 7th, 2011

Supposed to be taking Microkhan Jr. to his first major league baseball game today, an afternoon Yankees-Orioles tilt up in the Bronx, but the weather is looking ominous. I thus aim to curry favor with the rain gods by posting the song above from Max Tannone’s much-beloved Ghostfunk, recently highlighted on perennial podcast fave Fresh Produce. Because we all know how much weather-controlling deities enjoy Wu-Tang remix projects. I also hope they are fond of keeping little boys’ hearts intact; the kid will be crestfallen if we’re forced to end up at the Chuck E. Cheese in Harlem.

Comments Off on An Appeal to the Rain GodsTags:Ghostfunk·hip-hop·Max Tannone·music·Wu-Tang

A Pro’s Pro

September 6th, 2011

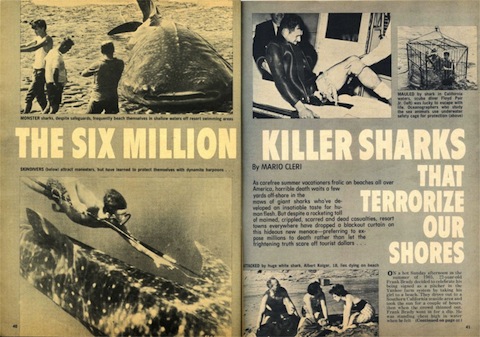

At the risk of alarming folks who have a vested interest in my creative progress, I must confess that the book-writing process is proceeding at a snail’s pace. In a wildly optimistic moment last month, I vowed to have two entire chapters done by Labor Day; now my best-case scenario is that I’ll have a single chapter done by day’s end, and even that isn’t a lock. The words flow much more quickly in theory than in practice.

Yet as much as I’d like to convince myself that all writers endure such struggles, that simply isn’t the case. I found it alternately illuminating and dispiriting to read this terrific 1984 interview with The Godfather author Mario Puzo, who was nothing if not productive. Prior to finding his fortune in Hollywood, Puzo labored as a pulp-magazine writer, penning sensationalist clip jobs under the pseudonym Mario Cleri (above). He spoke of just how many pages he could dash off in the name of pulling a family-sustaining paycheck:

Q. How many pages of a book bonus could you write in a typical day?

PUZO: I used to do a book bonus on the weekends, which was at least 60 pages. I never could write in the office, I had to work at home. When I was working on The Godfather, I was doing three stories a month, I was writing book reviews for The New York Times, Book World, Time magazine, and I wrote a children’s book [The Runaway Summer of Davie Shaw]. All at one time. And I was publishing other articles. I had four years where I must have knocked out millions of words.

I tell ya, it’s absolutely the best training a writer could get, to work on those magazines. You did everything.

Q: There’s no equivalent today.

PUZO: It’s a shame. If I had a son who wanted to be a writer, I wouldn’t even bother to send him to college. I’d get him a job up there as an assistant editor, leave him there for five years and he’d know everything. You’ve got to turn out a lot of copy.

Also worth noting from the interview, especially given the subject matter of my book: Vietnam didn’t play in the pulp world:

Q. Did you ever write a story on Vietnam?

PUZO: Yeah, I did one or two, but they were absolute poison. The readers didn’t like to read about it. That was very early on in Vietnam. We used to emphasize that Vietnam only had poison sticks. How the Poison Stick Army Beat America’s Ultra-Modern Weapons, shit like that.

Q. But it never went over?

PUZO: Nah, they hated it. Also we weren’t the heroes. Just like the Korean War—we used to call that The No Fun War. World War II was The Fun War. And you could get some mileage out of the Civil War and World War I. World War II was a bonanza. But Korea and Vietnam were losers.

I wish the interview had delved a bit more deeply into the notion of what constitutes a “Fun War,” and whether such a thing is even possible in the age of mass communication. Copious information creates a thousand shades of moral gray.

Face Off

September 2nd, 2011

When you’ve spent the better part of your adult life at the helm of an entire country, it must be awfully hard to accept a gold watch and fade into the sunset. I’m going to guess that playing bridge, hitting the country-club buffet, and working on your memoirs doesn’t give a type-A personality the same sort of thrill as hobnobbing with heads of state. So how many of us can be surprised to hear that Sir Michael Somare, the longtime prime minister of Microkhan fave Papua New Guinea, is having second thoughts about relinquishing his hold on power:

PAPUA New Guinea’s founding father and former prime minister Michael Somare will take up his seat when parliament sits again next Tuesday, his son Arthur said yesterday…

Earlier, Sir Michael’s daughter Bertha had emailed a media statement from Singapore, where he is recovering from three heart operations since April.

The statement, accompanied by Sir Michael’s signature, said: “Let me be clear. I am ready, willing and able to complete my term as the only legally elected prime minister of Papua New Guinea”.

It quoted Sir Michael, 75, as saying: “There has never been a vacancy in the position of prime minister.”

That last bit is certainly news to Papua New Guinea’s parliament, which declared the prime minister’s post vacant in early August, upon learning of Somare’s serious health problems. Peter O’Neill was elected in Somare’s stead, and the cockeyed optimists among PNG watchers were hoping he might finally do something about the nation’s endemic corruption and lack of security.

If Somare does show up on Tuesday as promised, the showdown on the parliament floor will make for some excellent political theater. Does anyone know if PNG’s equivalent of C-SPAN has a live Internet feed?

→ 2 CommentsTags:Papua New Guinea·politics·Sir Michael Somare

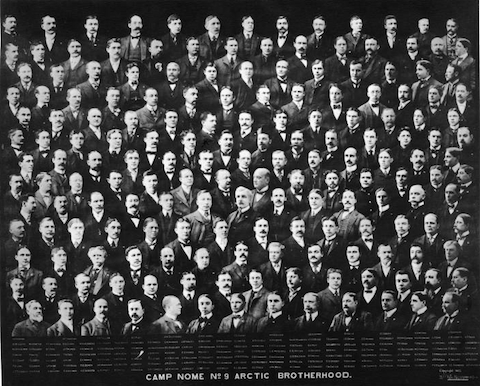

The Original Social Networks

September 1st, 2011

For those of us born after the invention of pencilin—presumably anyone and everyone who has ever checked into Microkhan’s universe—it’s difficult to fathom the esteem in which fraternal organizations were once regarded. Thumb through any society page from the first half of the 20th century and you’ll doubtless encounter one article after another about the estoerica of Kiwanis or Roatarian politics—the fierce squabbles over leadership positions, the spats over the right date on which to hold the annual potluck. In the era before cheap travel and mass communication enabled businessmen to strike deals with people who lived beyond their county’s borders, the ties created by fraternal bonds were integral to making commerce happen—and, one suspects, to giving men an outlet for energies that are currently expended on professional football and Internet pornography.

It makes perfect sense, then, that Alaska’s early white settlers transported the fraternal-organization concept to their new homes. The foremost of the resulting clubs was the Alaskan Brotherhood, founded in 1899, which managed to garner over 10,000 members before it disintegrated in the late 1920s. Because of the lack of leisure options in the frozen north, the organization was fond of staging shows—some of admirable quality, others that were appallingly racist.

The Arctic Brotherhood may have lasted until the dawn of the Great Depression, but its heyday was brief—everything went downhill after 1909, when a schism occurred over the question of whether residents of the Lower 48 could be allowed to join, even on a ceremonial basis. The Dawson Daily News covered the controversy:

Considerable agitation is evidencing itself in the local Arctic Brotherhood circles over the news that Bill Taft is to be initiated down in Seattle along with about 200 others who are trying to climb in the band wagon when the president rides the goat, and there threatens to be a mighty upheaval is this desecration of the brotherhood’s ideals is really pulled off.

There are shades here, of course, of controversies of more recent vintage, concerning some radical Alaskans’ antipathy toward those scoundrels in the Lower 48.

Much more Arctic Brotherhood history on the site of its modern incarnation.

(Image via Alaska’s Digital Archives)

→ 3 CommentsTags:Alaska·Arctic Brotherhood·fraternal organizations·racism

The Underwhelmer

August 31st, 2011

Hacking my way through a tricky part of the book today—a section in which I must encapsulate the tumult of late-1960s South Vietnamese politics in the space of two paragraphs. The chore has me focusing on the figure of Nguyen Cao Ky, the air marshal who became South Vietnam’s prime minister in 1965 (and who recently passed away). While his achievements, or lack thereof, have been long debated, one thing is for sure: Nguyen had no illusions about his capabilities, as evidenced by his memories of the post-coup military meeting that brought him to power:

I asked all of [the officers] — 60 or 70 of them, you know, in the room. I said, “Okay — ah, one more time. Anyone want to be prime minister?” And they said no. So [Gen. Nguyen Van] Thieu said, “I propose Ky.” And all of them just stood up and accept the offer. But then I, I didn’t give them the answer. I said, “I have to go back and talk with my wife first.” And when I told her about that offer, you know, she was not excited. She said, “Oh no! Not that job! Not as a prime minister!” Ha, ha. I’m not a good politician. I’m not a good diplomat. You know, I think all I know, the only thing I can do well is, you know, flying the airplane. I said, “Well? What can I do now?”

On the plus side, he did end up giving the world a daughter who revolutionized the world of Vietnamese-language aerobics.

Comments Off on The UnderwhelmerTags:military·Nguyen Cao Ky·politics·Vietnam·Vietnam War

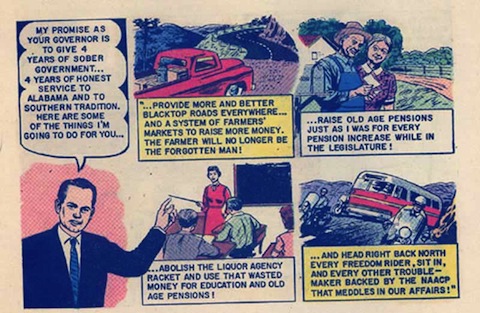

Commerce Above All

August 30th, 2011

Those who’ve been keeping score might have noticed a recent Microkhan obsession with visual communication—particularly the way in which simple illustrated material can be used to convey complex messages. This is an interest that dates back to my first exposure to Chick tracts, and has now ramped up with all the energy I’ve been pouring into evaluating the efficacy of wartime propaganda.

My latest discovery on this front raises a different, more philosophical issue: how some people are able to divorce their personal beliefs from their business, and some are not. Comic-book creator Malcolm Ater certainly fits into the former category. His Commercial Comics Company seemed perfectly willing to create tales for any paying customer, from the American Gas Association to the Congress of Industrial Organizations to George Wallace (above). The story of how the Illinois-bred Ater eagerly spread Wallace’s odious message is recounted here:

In 1960 Ater traveled to Alabama to meet with George Wallace, who was running for governor. By Malcolm’s retelling, Wallace leaned across his desk and stated “I don’t see how a damn Yankee like you can come down here to Alabama and help me get elected.” Ater replied “Well, Judge, if you’ll recall, I came down here a few years ago and worked for John Patterson and helped defeat you!” Wallace and he became friends and the result was the comic Alabama Needs the Little Judge, George Wallace for the Big Job. This book is pro segragationist and in it Wallace promises to send “back north every freedom rider, sit-in, and every other troublemaker” sent by NAACP.

There is no hint anywhere in Ater’s biography that he harbored political views that were anything like Wallace’s—if they were, I very much doubt he would have volunteered his services to Madonna in the mid-1980s. And so I find myself wondering whether there was ever a moment’s doubt in Ater’s mind as to whether he should take the Wallace gig, or if there really is a breed of human who can banish all personal thoughts in the service of commerce.

In a sense, Ater reminds me of the late Lee Atwater, who reportedly only became a Republican in order to rebel against the fact that he was surrounded by Democrats while growing up in South Carolina. The story goes that Atwater didn’t care a whit about the issues his candidates espoused—he only cared about winning elections, much as Ater only cared about getting paid to create comics. Is there something quintessentially American about that approach to business?

Another classic (and notorious) Ater comic here. If I had been a schoolkid in Grenada in 1984, I would’ve been damn terrified of those Cuban monsters.

→ 6 CommentsTags:Alabama·comics·George Wallace·Grenada·Lee Atwater·Malcolm Ater·morality·philosophy·politics·racism

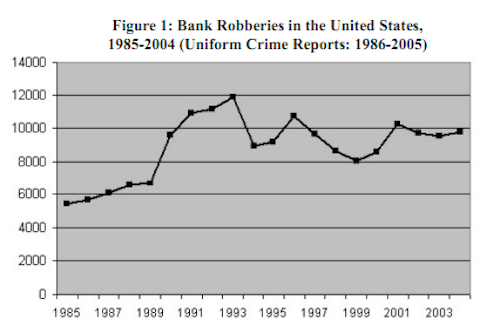

A Fat Lot of Good

August 29th, 2011

A recent deep-dive into the history of the dye pack got me wondering about long-term trends in bank robbery. So much brainpower has gone into devising gadgets and strategies that allegedly help financial institutions minimize the risk of getting hit. Are those security investments working?

That’s a tougher question to answer than I had anticipated, as the basic stats on the crime don’t seem too favorable. As you can see above, the sheer number of robberies has increased since the mid-1980s, more than keeping pace with population growth. On top of that, robbers are enjoying ever greater odds of escaping arrest (PDF):

Although the clearance rate for bank robbery is among the highest for all crimes, the rate has declined. In the United States, bank robbery clearances have dropped from 80 percent in 1976 to 58 percent in 2001; clearances vary by region, from as low as 34 percent to as high as 80 percent.

That isn’t to say that all those crafty anti-robbery techniques have been for naught. A big factor in the crime’s growth seems to be the proliferation of small suburban branches, where police response time is much greater than in central areas. Without innovations such as single-door entryways, dye packs, and greeters, there’s no telling how high the rate might be today.

More important, there’s some really interesting cost-benefit analysis going on here. The average take from each bank robbery is just around $4,000, and about 60 percent of all stolen money is eventually recovered. A quick back-of-the-envelope calculation thus concludes that American banks lose just around $16 million to robber each year—peanuts compared to liabilities they might face if a botched robbery led to customers’ deaths. As a result, there is little incentive for banks to do much to change the status quo—the current situation, in which bank robbery is nothing more than a well-managed risk, suits them just fine.

The Reset Button

August 26th, 2011

Thanks a mil for bearing with the light posting this week. Was hoping to reward y’all with an entry about Olmec jaguar worship, but the brain ain’t working like it should—the consequence of a horrendous JetBlue delay and general work-related exhaustion. Back at full strength after Hurricane Irene passes over Microkhan world headquarters this weekend; in the meantime, please check out the excellent podcast version of my latest Wired story. Major plaudits to the narrator for nailing all those tricky pronunciations, and for making the minutiae of slot-machine hacking seem every bit as sexy as the finest pulp vixens.

Comments Off on The Reset ButtonTags:slot machines·Wired

What Would Buddha Do?

August 24th, 2011

I do not believe the prince who renounced the world in order to attain Enlightenment would approve of these copyright shenanigans in Taiwan:

The funeral industry has been rocked by a lawsuit filed by a music company that accuses funeral homes of intellectual property right (IPR) infringement for playing Buddhist chants and pop music during services.

Music and Buddhist chants during funerals are usually provided by the funeral homes, mostly using a gadget called the Electric Buddhism Sutra Player (above) or music CDs.

However, one music company feels the use of the sutra player constitutes as copyright infringement and began recording audio and video footage of services earlier this year at funeral homes all across the nation. It then filed lawsuits against a number of funeral homes, demanding a copyright fee of NT$500.

There’s actually an interesting intellectual-property concept at the heart of this brouhaha—namely, whether unique interpretations of previously published material should enjoy some measure of legal protection. (I, for one, would not mind a whit if Lily Allen gets a dash of cash every time someone plays her version of “Womanizer.”) But the key there is “unique”—the litmus test should be whether there was creative sweat poured into the endeavor. In the case of these sutra players, the only hard work consisted of coding the ancient tunes onto chips. I very much doubt the programmers thought they were adding a new level of insight.

As is so often the case in situations like this, most Taiwanese funeral homes are reacting not by coughing up the requested money, but rather by simply putting the grieving families in charge of the music—thereby removing the commercial element of the “performance.” How the maker of the Electric Buddhism Sutra Player didn’t see that maneuver coming from a mile away is beyond my powers of comprehension.

→ 1 CommentTags:Buddhism·Electric Buddhism Sutra Player·gadgets·intellectual property·law·music·religion·Taiwan

Komrad Ivan

August 22nd, 2011

Greetings from a rather random corner of Southern California, where I find myself pursuing the heart-and-soul of my next book. While I’m busy interviewing an eyewitness to historic events that the bulk of Americans have long forgotten, please take a moment to delve into the University of Nebraska’s rich trove of government-issued comics. Given Microkhan’s longtime fascination with all things Soviet—damn you, Amerika and Hendrick Smith—the illustrated booklet about the technology of Warsaw Pact armies(above) couldn’t help but make an impression. An early precursor to the PowerPoint presentation, perhaps.

Comments Off on Komrad IvanTags:Cold War·comics·military·Soviet Union

Drop and Gimme Twenti

August 18th, 2011

An otherwise innocuous story about Fiji’s efforts to combat littering reveals this golden information nugget about law enforcement in Papua New Guinea:

“We did some relative studies and found that in Papua New Guinea if you are found littering – you are asked by the authority to do push-ups. For us here we tell them to pick their rubbish up immediately and also clean the surrounding environment,” Mrs Tagicakibau said.

I haven’t been able to confirm this factoid, but if it’s true, it represents a lot that ails Papua New Guinea. For starters, there is no mention of push-ups in the nation’s criminal code, meaning that the cops just made this punishment up on their own—a hint that there’s a serious break down in the rule of law. Second, has anyone in Port Moresby bothered to study the Stanford Prison Experiment? I thought that provided fairly good evidence that using push-ups as punishment was a recipe for disaster.

(N.b., the italicized word in this post’s title is Tok Pisin for “twenty.” Full dictionary of the language here.)

Comments Off on Drop and Gimme TwentiTags:Fiji·law·Papua New Guinea·police·Stanford Prison Experiment

The Empty File

August 17th, 2011

As part of my ongoing, book-related effort to gain a better understanding of the Vietnam War, I recently started diving into the documentary series based on Stanley Karnow’s Vietnam: A History. (Yeah, I know, I should’ve started with the source material—my bad.) I’ve found the first episode particularly enlightening, since part of my book will deal with French opposition to Vietnam—opposition obviously rooted in France’s disastrous experience at Dien Bien Phu. The television version of Karnow’s work really nails the exact nature of France’s failings, both politically and militarily. A classic case of imperial hubris, or so it would seem.

The quote that best sums up the catastrophe comes from a French captain named Jean Pouget. In recalling the 1953 arrival of General Henri Navarre, the fifth French commander in Vietnam in as many years, Pouget says that a concerted effort was made to develop what might now be termed a “communications strategy.” But for some reason, the effort never went anywhere:

When General Navarre arrived, he opened a file right away and on that file I wrote “War Goals.” We looked for what to tell the troops. Well, until the end this file remained practically empty. We never could express concretely our war goals.

I reckon the same could be said for the American military a decade or so later. The question I have to address, then, is how this lack of clear goals affected the psychological well-being of the men in the field, especially after their fighting days were done. There is actually a case to be made (most notably by Jonathan Shay in Achilles in Vietnam) that the uncertain nature of the mission in Vietnam contributed to the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among that conflict’s veterans. Perhaps it is not only the horror of combat that warps the mind, but also the anxiety of not knowing whether one’s supreme sacrifices were truly for a greater good.

(Image above: One of the 3,300 French prisoners-of-war to returns home after Dien Bien Phu. Seven thousand of his comrades perished will in Viet Minh custody.)

Comments Off on The Empty FileTags:Achilles in Vietnam·Dien Bien Phu·France·military·psychology·PTSD·Vietnam War

The King Abides

August 16th, 2011

Plowing back into the book this morning, after losing all of yesterday to Microkhan Jr. duties. Really scrambling to get some work done before heading out to California this weekend, for an interview of the utmost importance. In my brief absence, please check out the latest live mix from DJ Assault, one of the most treasured members of the Microkhan musical pantheon. Great to hear that the man is now running his own record label back in Detroit, the city where I first discovered his vinyl offerings back in the late 1990s. He’s been in regular rotation on the digital jukebox ever since, though obviously less so in recent days—permissive as I am, I would have to give back my “Father of the Year” mug if I ever allowed the kid to hear the likes of this.