Absolutely nothing in the tank today—totally drained by a fifth consecutive day of solo parenting. Gotta use all available mental bandwidth to start outlining a forthcoming Wired opus ’bout an ingenious casino scam. You know the drill—enjoy the prime example of Malaysian movie music above, and catch you again as soon as I’m able.

Swounds

February 17th, 2011

“The Basest Treachery is Often Employed”

February 16th, 2011

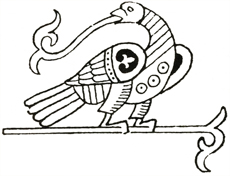

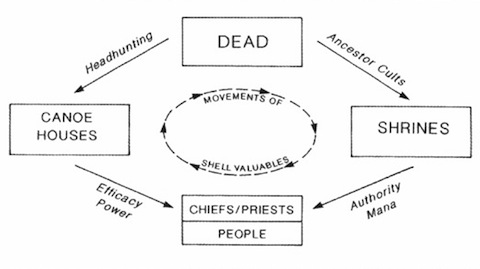

The ruins on Nusa Roviana, an island off the coast of New Georgia, include a baker’s dozen worth of skull shrines. These mystical fixtures were vital to the political structure of Nusa Roviana’s society, which centered on all-powerful chiefs who claimed an ability to communicate with deceased ancestors.

But the islands’ inhabitants were not only interested in preserving their forebears skulls; they were also enthusiastic headhunters who believed it imprudent to proceed with any major endeavor without securing a fit offering for the gods. A British anthropologist described the community’s headhunting zeal in 1899—as well as the raiders near total disregard for formal rules of engagement:

No canoe-house can be completed and no canoe launched with a head being obtained. They make long voyages in their large tomakos, or head-hunting canoes, for the purpose of securing heads, the chief hunting-ground at the present time being the two island of Choiseul and Isabel, ninety to one hundred miles away, which, however, are becoming somewhat “worked out.” The basest treachery is often employed. They will at times visit a village as friends, and, after staying for a day or two, at a given signal turn upon their hosts, and either kill them or take them alive. Such a case occurred while I was at Rubiana. At other times they will surprise or cut off a party fishing on the reef, and no matter whether they are men, women, or children, the heads count. The heads, after being slightly smokes, are stuck up along the rafters of the roof in the canoe-houses, and I have myself counted thirteen recent heads in a house in Sisieta.

More on the purpose of skull accumulation on Nusa Roviana here.

Comments Off on “The Basest Treachery is Often Employed”Tags:anthropology·headhunting·New Georgia·Nusa Roviana·Solomon Islands

The Quinby Smoker

February 15th, 2011

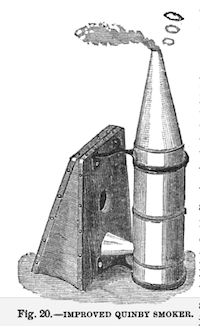

Behind every mass-market product is an invention that made its creation cost-effective. In the case of honey, that technological marvel is the humble bellows smoker, which produces a non-toxic haze with the power to chill out agitated bees. It does so by messing with a colony’s communications system: Sentries are supposed to alert warriors to the approach of a threat (such as a beekeeper), a task they’re designed to accomplish by releasing powerful pheromones. But the smoke interferes with the sentries ability to secrete those key chemicals, and so the highly venomous soldiers ever get the signal to attack.

Behind every mass-market product is an invention that made its creation cost-effective. In the case of honey, that technological marvel is the humble bellows smoker, which produces a non-toxic haze with the power to chill out agitated bees. It does so by messing with a colony’s communications system: Sentries are supposed to alert warriors to the approach of a threat (such as a beekeeper), a task they’re designed to accomplish by releasing powerful pheromones. But the smoke interferes with the sentries ability to secrete those key chemicals, and so the highly venomous soldiers ever get the signal to attack.

For centuries, the problem for beekeepers was how to produce a steady, long-lasting stream of smoke that would directly target the hive. Finally, in 1870, the great Moses Quinby devised an efficient bellows smoker that made modern beekeeping possible. A 1947 encyclopedia of the profession’s arcana paid tribute to Quinby’s genius:

One can drive cattle and horses, and to some extent even pigs, with a whip, but one who tries to control bees without smoke will find to his sorrow that the rest of the animal kingdom are mild in comparison, especially so far as stubbornness and reckless fearlessness of consequences are concerned. One may kill them by the thousands or may even burn them up with fire; but the death agonies of their comrades seem only to provoke them to a new fury, and they rush to the combat with a relentlessness which can be compared to nothing better than a nest of yellow jackets that have made up their minds to die, and to make all the mischief they possibly can before dying. It is here that the power of smoke comes in; and to one who is not conversant with its use it seems simply astonishing to see bees turn about and retreat in the most perfect dismay and fright, from the effects of a puff or two of smoke from a mere fragment of rotten wood. What could beekeepers do with bees at times, were no such potent power as smoke known?

Much more on the history of bee smokers here, including a rundown of who benefited from the fact that Quinby neglected to patent his landmark invention.

→ 2 CommentsTags:animals·beekeeping·bees·food·honey·Moses Quinby·technology

Avoiding the Dreaded Shoelace Belt

February 14th, 2011

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4lHwQa68HIo&feature=player_embedded#at=262

This is gonna be a rough week, as we’re solely in charge of Microkhan Jr. while the Grand Empress is off doing her thing in Vega$. The good news is that, with the aid of several Yuenglings last night, I believe that I’ve been able to reset my internal clock to deal with the situation at hand. But time will be extra-precious these next few days, so expect more factoid-y posts than usual. And today I can only give you two small Valentine’s Day gifts: the finest Nas verse ever (NSFW, of course), and a link to one of my favorite modern love poems. The kickout on the latter is incredible:

Love does not last, but it is different

from the passions that do not last.

Love lasts by not lasting.

Isaiah said each man walks in his own fire

for his sins. Love allows us to walk

in the sweet music of our particular heart.

Even more highly recommended from Jack Gilbert’s body of work (though a fair bit darker): “Tear It Down”

Enjoy, and see you back here tomorrow for a bit of Taiwanese crime history. Or maybe Romanian viper farming. All depends on my success in getting Microkhan Jr. to preschool on time.

Comments Off on Avoiding the Dreaded Shoelace BeltTags:hip-hop·Jack Gilbert·music·Nas·poetry·Valentine's Day

The Greenless Island

February 11th, 2011

Abandoned human settlements are a pet topic ’round these parts, so I couldn’t resist the urge to post about the Japanese island of Hashima (aka Gunkanjima). Entranced by this haunting collection of photos, I tracked down a primer on the coal-mining outpost’s tragic history. As is so often the case with operations designed to pillage the Earth in the quickest, most cost-efficient manner possible, the men who did the dirty work suffered greatly—especially during World War II, when Korean slave labor was employed. The situation got markedly better in the post-war period, but Hashima still sounds like it was a rather glum place to make one’s living:

The population of Hashima reached a peak of 5,259 in 1959. People were literally jammed into every nook and corner of the apartment blocks. The rocky slopes holding most of these buildings comprised about 60 percent of the total island area of 6.3 hectares (15.6 acres), while the flat property reclaimed from the sea was used mostly for industrial facilities and made up the remaining 40 percent. At 835 people per hectare for the whole island, or an incredible 1,391 per hectare for the residential district, it is said to be the highest population density ever recorded in the world. Even Warabi, a Tokyo bedtown and the most densely populated city in modern Japan, notches up only 141 people per hectare…

The community depended completely on the outside world for food, clothing and other staples. Even fresh water had to be carried to the island until pipes along the sea floor connected it to mainland reservoirs in 1957. Any storm that prevented the passage of ships for more than a day spelled fear and austerity for Hashima.

The most notable feature of the island was the complete absence of soil and indigenous vegetation. Hashima, after all, was nothing more than a rim of coal slag packed around the circumference of a bare rock. A movie shot there by Shochiku Co. Ltd. in 1949 was aptly entitled Midori Naki Shima (The Greenless Island).

Mine-owner Mitsubishi eventually made a calculated business decision to abandon Hashima, thereby creating one of the eeriest ghost towns this side of Kadykchan. It now resembles something straight out of one of my childhood touchstones: the hollowed-out cities of the third Robotech series, set in a not-too-distant future in which an alien race has conquered the planet. The only thing missing on Hashima are the heaped-up carcasses of soldiers and Cyclones. (Yeah, Robotech was dark like that.)

More on Hashima via this 2002 documentary.

→ 7 CommentsTags:coal·ghost towns·Hashima·Japan·mining·urban decay

Caught in the Grip

February 10th, 2011

Deadline day here at Microkhan headquarters, so please make do with some downbeat Canadian dream pop for now. Listen closely for a moment that obviously made a big impact on Dan the Automator, seeing as how he copped it for a Deltron 3030 chorus.

Comments Off on Caught in the GripTags:Dan the Automator·Deltron 3030·hip-hop·music·The Poppy Family

…But Somebody’s Gotta Do It

February 9th, 2011

A dozen years ago, this New York Times Magazine story wormed its way into my memory banks by citing a single, jaw-dropping stat: “About 70 percent of all Indian motel owners—or a third of all motel owners in America:mdash;are called Patel, a surname that indicates they are members of a Gujarati Hindu subcaste.” After reading that tidbit on page one, how could I resist the urge to plow through the remaining 5,000 words?

A dozen years ago, this New York Times Magazine story wormed its way into my memory banks by citing a single, jaw-dropping stat: “About 70 percent of all Indian motel owners—or a third of all motel owners in America:mdash;are called Patel, a surname that indicates they are members of a Gujarati Hindu subcaste.” After reading that tidbit on page one, how could I resist the urge to plow through the remaining 5,000 words?

The main takeaway from the piece wasn’t just that Indians have come to dominate America’s mid-market hospitality industry, but that certain immigrant groups have long made their way on these shores by specializing in particular industries. As the story’s author explained:

America’s motels constitute what could be called a nonlinear ethnic niche: a certain ethnic group becomes entrenched in a clearly identifiable economic sector, working at jobs for which it has no evident cultural, geographical or even racial affinity.

I don’t mean Italians owning pizzerias, or Japanese people running judo schools. I mean, to use an obvious example, the Korean dominance of the deli-and-grocery sector in New York — a city where the Chinese run most laundries and Sri Lankans, in case you didn’t know this, run most porn-video stores. Or the Arabs in greater Detroit, who have a stranglehold on gas stations, or the Vietnamese who monopolize nail salons in Los Angeles. Farther afield, I could mention London’s taxi drivers, sharp-tongued in their big black cars, many of whom are Jews from the city’s East End; or the security guards outside New Delhi’s more affluent residences, virtually all of whom are Nepalese; or the prostitutes in the United Arab Emirates, who are so often women from Russia.

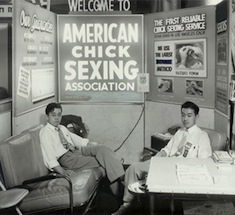

There is, of course, usually a prosaic reason why a group got involved in its preferred line of work. A perfect example of this is the way in which Japanese-Americans came to control the chick-sexing profession in the 1940s and ’50s.

This tale of economic triumph has a single hero: S. John Nitta, who founded the American Chick Sexing Association in 1938. During the war, when over 100,000 of his fellow Japanese-Americans were interned, Nitta continued to train and certify sexors; once the conflict ended, former internees turned to chick sexing as one of their few routes to economic advancement. Nitta was compelled to open up new training facilities, leaving behind his initial schools to be run by fellow Japanese-Americans. By the dawn of the Eisenhower Era, well over 90 percent of America’s chick sexers were of Japanese origin.

But Japanese-Americans lost this “nonlinear ethnic niche” quite quickly—partly because the next generation moved into more remunerative professions, but also because the advent of feather sexing opened up the enterprise to less skilled workers. But Nitta’s association is still with us, though it’s now down to two employees. I wonder if they still hand out these nifty certificates.

→ 4 CommentsTags:chick sexing·economics·immigration·Japan·S. John Nitta

Devil in the Details

February 8th, 2011

I’m juggling a pair of true-crime yarns at present, and thus taking a keen interest in the contortions of an ambitious robber’s mind. What I’m starting to surmise is that even the sharpest crooks often lack a key mental skill: the ability to plan an endgame. Though their schemes may be brilliant on paper, criminals seldom put much thought into the details that truly matter. In other words, Dalton Russells are rare in the non-celluloid realm.

There is perhaps no greater illustration of this fact than the curious case of Eastern Air Lines Flight 393. In June of 1972, this Greensboro-to-Atlanta flight happened to be carrying $3 million worth of untraceable securities. A quintet of men somehow got hip to this fact, and plotted what seemed to be the perfect crime:

When Eastern Air Lines Flight 393 took off from Greensboro, N.C. at 9 p.m. Tuesday night it carried in its cargo hold $3 million in securities and a box containing a 39-year-old man. The latter, say the FBI, planned to steal the former…

Grant Clyde Cralley had been shipped prepaid in a cardboard and wood box about three-feet square, FBI agents said. The box had a removable door and was equipped with oxygen in case he needed it.

Alas, as it would later emerge during legal proceedings, the conspirators didn’t realize that cargo is stacked in the belly of planes, with the biggest items on the bottom. And so the door to Cralley’s crate was held shut by heavy mail sacks, and he was never able to emerge from his hiding place during the short flight.

The question then is why criminal minds typically make such basic miscalculations, even when their larger schemes exhibit a flair for intelligence. Dishonesty may be a thief’s primary shortcoming, but carelessness ranks a close second. I reckon a civil society should be grateful for that fact.

The Opulent Goodbye

February 7th, 2011

The late Hmong military leader Vang Pao is currently being memorialized in grand fashion, as his culture’s traditions dictate:

[Vang Pao’s] funeral — six days and nights, with 10 cows slaughtered and stir-fried each day — has become a send-off for the ages. It began last Friday, his body borne on a horse-drawn carriage through the streets of downtown Fresno, throngs of grieving Hmong lining the way. Scottish bagpipers played “The Green Hills of Tyrol” and two T-28 planes, the aircraft piloted by Hmong guerrilla fighters in the Vietnam War, flew overhead.

And the funeral rolled down a long red carpet through the weekend, as thousands more Hmong from across the country, and some from as far away as Thailand and France, strode into the convention center of this farming capital of California to say goodbye.

Such lavish funerals obviously serve a purpose beyond just allowing a man’s admirers to grieve. They are created as evidence that a marginalized community is strong enough to survive its leader’s passing. This has always been the subtext in those outrageously opulent Mafia funerals; they’re not just about showing how much wealth and power a crook had accumulated, but also an attempt to demonstrate that his criminal realm will continue on in his absence. If a capo‘s underlings or successors can effectively gather the funds necessary to pay for this many flowers—not to mention work out the logistics of the procession and the afterparty—then surely they can comandeer the late man’s rackets.

The trouble is, those who lack power still retain the competitive instinct, and so desire lavish funerals that have no political motive. This can be ruinous not just to a family, but to a society; in Ghana, for example, hands are frequently wrung over the percentage of income that is spent on ornate coffins. And for well over a century now, people in the U.S. have rightly feared that too much familial wealth is dedicated to big send-offs, rather than guaranteeing the security of the ensuing generations. The New York Times chimed in on the topic 125 years ago:

It would be surprising to learn how common it is for families in this and other large cities to overtax themselves to provide paraphernalia for the tomb. Not infrequently they spend every dollar that has been left, even exceeding the amount sometimes, and in many instances anticipating a large share, if not all, the insurance upon the life of the deceased. Not a few instances might be cited in which money has been borrowed to defray funeral expenses when, if the funeral and been modestly and properly managed, there would have been no need of borrowing at all. What an unworthy return is this to the man who has probably worked hard for years, and given himself less anxiety to save something for his family in the event of his sudden death! Of what advantage is it to him, in his sheeted sleep, that there should be a few more flowers or carriages, that the coffin should be real rosewood, or the handles genuine silver? All has ended; all is well with him. To him money is no longer essential; whatever he has gained beyond necessary expenditure, should be devoted to the service of the living.

This is why, when our time comes, this particular khan would like to be cremated and have the ashes strew somewhere meaningful—the acropolis at Marcus Garvey Park, perhaps, or the the subway platform where the Grand Empress entered the picture. However, it would also be nice if I could leave behind just enough money to fund a marble Microkhan Memorial Bench—to be manned by two 24-hour security guards armed with cattle prods, who will strictly enforce a “no sitting” policy. Is that too much to ask?

(Image via the biography of Calogero Vizzini)

Comments Off on The Opulent GoodbyeTags:economics·funerals·Ghana·Hmong

“Champ of the Ivories”

February 4th, 2011

I have done my earnest best to keep self-promotion to a minimum on Microkhan, while also refusing ads in order to preserve the pristine reading experience you’ve (hopefully) come to know and love. But, alas, I’m going to ask you to endure a bit of jersey-popping on this cold winter morn, as I try once more to convince y’all to invest a few moments and dollars in my latest major project: “Piano Demon,” the debut story for new digital-only publisher The Atavist.

I first stumbled across Teddy Weatherford’s name while researching Now the Hell Will Start; I rather randomly spotted his obituary while trolling through a reel of old Chicago Defender microfilm. Ever since, I’ve been more than a bit obsessed with the arc of this great pianist’s life; a onetime child coal miner in Pocahontas, Virginia, he eventually became the most celebrated jazzman in Asia. A fixture of the elegant hotels and clubs where the colonial elite gathered to wallow in decadence while the continent descended into war, Weatherford provided the soundtrack for the last gasp of empire.

“Piano Demon” is exactly the sort of yarn that I’d love to make my professional bread-and-butter: a deeply reported nonfiction epic that blurs the line between truth and art. More important, I’m thrilled to have had the opportunity to shape the look and feel of the finished product with such an excellet, creative crew. I feel like “Piano Demon” is part of something embryonic but important—a reinvention of storytelling for the Tablet Era.

If you dig Microkhan or any of my other work, I beseech you to give “Piano Demon” a whirl—not only because I’m so proud of the project, but also because I get a fair cut of every purchase. It’s a cheap way to show your support for your humble narrator, plus you’ll learn more than you thought possible about coal-mining accidents, anti-jazz activism, the Shanghai underworld, and Bombay liquor laws, to name just a few of the topics covered.

If you can swing the technology, the iPad/iPhone version is highly recommended; the extra dollar buys you music, extra images, and a bevy of interactive features. But no worries if you’re currently un-Appled; the Kindle version is a winner, too, and it can be read on a litany of devices (including PCs and Macs) by downloading one of Amazon’s free apps. (Also, if you purchase the Kindle version, you can continue to help “Piano Demon” outrank the Mötley Crüe biography.)

And there endeth the self-promotion. Back to your regularly scheduled programming next week: kidnapping rumors, the pig economy in Papua New Guinea, and the gaudy splendor of Mafia funerals.

(Image of Calcuttans transporting a piano via the Digital South Asia Library)

→ 7 CommentsTags:books·Calcutta·Chicago·China·coal·India·jazz·music·Piano Demon·Teddy Weatherford·The Atavist

The Fanged King

February 3rd, 2011

The granddaddy of Malaysian vampire flicks, 1968’s Raja Bersiong tells the tale of a pre-Islamic king who develops a taste for human blood—a culinary affection that eventually leads him to grow long fangs, and then (spoiler alert!) to be killed by his subjects for paying more attention to his snacks than his royal duties. As related here, the movie was sort of the Heaven’s Gate of late 1960s Malaysian cinema:

As has often happened when a film industry is at a moment of crisis, Malay Film Productions (MFP) tried to spend its way out of trouble by making an expensive color and widescreen epic that could turn the tide. Raja Bersiong cost RM750,000, which was more than ten times the cost of the average film. The film was directed by Jamil Sulong and employed a Japanese crew, causing major production and communication problems. Even though the story was written by Malaysia’s first Prime Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman, and was a nationalist epic set in northern Malaysia, the film failed at the box office.

Hmmmm…any chance it was unwise to hire a politician to write a horror flick? I certainly wouldn’t have wanted Margaret Thatcher doing the screenplay for 28 Days Later.

Check out the rest of the movie here; part three is highly recommended.

Comments Off on The Fanged KingTags:Malaysia·movies·Raja Bersiong·vampires

The Golden Age of Twice-Cooked Pork

February 2nd, 2011

Apologies to my vegetarian readers for what is about to commence: a post about the grisly business of producing pig meat, a delicacy that I seek out far more often than my arteries would like. (I will perform nearly any feat of self-abasement in exchange for some top-notch lechón.)

Though I’m accustomed to reading about expensive cuts of pork, I know little about the industrial system that gives America its much-beloved riblets. And so I was instantly grabbed by a snippet of news making the ag-industry rounds: the Hypor Maxter has arrived:

Hypor is pleased to announce the addition of the Hypor Maxter to its North American terminal boar portfolio. Exceptionally lean, efficient and fast growing, this Piétrain line sits next to Hypor’s Kanto and Magnus Duroc terminal lines (including the DGI and Shade Oak populations). The addition provides producers in Canada and the United States with a comprehensive selection of terminal lines designed to optimise on-farm efficiency while meeting the diverse needs of the North American pork industry.

Originally developed by France Hybrides in 1971, the line was acquired by Hypor in 2008. The Hypor Maxter has achieved widespread commercial success in Europe where it is recognised for being the fastest growing Piétrain in the world. Recent Canadian commercial trials using imported semen have validated European results and demonstrate significant opportunity for the genes in the North American pork value chain. With ever increasing pressure on cost of production, the time was right to introduce the Hypor Maxter line to North America.

Hypor Maxter great grandparent males and females were imported to Manitoba, Canada in July 2010 from Hypor’s Sichamps nucleus in France. Once Hypor and federal inspection processes were complete, the Hypor Maxters were moved from the isolation facility to the Lockport, Manitoba nucleus facility in November 2010. Maxter boars are also being placed in Hypor’s Greenhill Gene Transfer Center and semen will be available for phase two commercial evaluation with strategic partners across Canada and the United States in early 2011.

There’s a lot to chew over here, such as the ethically dicey proposition that a mammalian genetic profile can be transferred between companies like surplus desks. But I’d like to focus on the upshot of the Hypor Maxter’s North American rollout: continued access to dirt-cheap pork, for better and for worse. The Maxter’s chief selling point is its growth potential—that is, it gets mighty huge in a relative hurry, thereby keeping producer costs in check. But the meat quality seems to be in question, as evidenced by this 2003 study comparing Pietrains to Durocs:

Subjective meat quality scores for color, marbling, and firmness (1 to 5 scale) were more favorable for Duroc-sired progeny. Furthermore, chops from Duroc progeny had higher 24-h pH (5.53 vs. 5.48, P < 0.001) and Minolta a* (17.33 vs. 17.04, P < 0.05) with less percentage drip loss (2.88 vs. 3.80, P < 0.001). No differences were detected between Duroc- and Pietrain-sired progeny for Minolta L* (54.77 vs. 55.37) or b* (7.58 vs. 7.58) objective color scores, percentage cooking loss (28.63 vs. 29.23), or Warner-Bratzler shear force (6.94 vs. 7.11 kg).

So expect your pan-fried dumplings to remain vanishingly cheap in the coming years, thanks to the blessings of science. But speaking for myself alone, I won’t be able to tuck into cheap pork with quite the same abandon knowing that I’m feasting upon a slice of Hypor’s “terminal boar portfolio.”

→ 2 CommentsTags:agriculture·animals·food·genetics·Hypor Maxter·meat·pigs·pork

The Grim Handiwork of Man

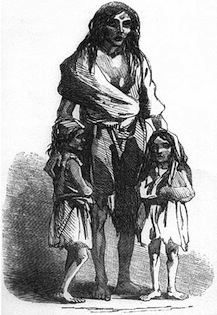

February 1st, 2011

In researching my Teddy Weatherford yarn for The Atavist, I was compelled to revisit a tragic event that I described in Now the Hell Will Start: the Bengal famine of 1943, which ultimately claimed the lives of 3 million Indians. In the book, I detail how a bare modicum of foresight could have prevented the catastrophe; the British should have realized that Burma, the source of most of Bengal’s rice, was vulnerable to Japanese invasion, and had a contingency plan in place. Delving into the topic once more for “Piano Demon,”, however, I came across some scholarship that asserts that the famine persisted due to Winston Churchill’s malevolent intervention; the claim is that Churchill viewed the famine as an excellent way to weaken India’s burgeoning independence movement, and so secretly urged that nothing be done to feed the suffering Bengalis. (Pointed rebuttal to that argument here.)

In researching my Teddy Weatherford yarn for The Atavist, I was compelled to revisit a tragic event that I described in Now the Hell Will Start: the Bengal famine of 1943, which ultimately claimed the lives of 3 million Indians. In the book, I detail how a bare modicum of foresight could have prevented the catastrophe; the British should have realized that Burma, the source of most of Bengal’s rice, was vulnerable to Japanese invasion, and had a contingency plan in place. Delving into the topic once more for “Piano Demon,”, however, I came across some scholarship that asserts that the famine persisted due to Winston Churchill’s malevolent intervention; the claim is that Churchill viewed the famine as an excellent way to weaken India’s burgeoning independence movement, and so secretly urged that nothing be done to feed the suffering Bengalis. (Pointed rebuttal to that argument here.)

As I waded back through my notes on the Bengal famine, I became more interested in examining a frequent assertion of modern historians: that all famines are created by man, rather than nature. That line of inquiry led me to this thorough look at the Vietnamese famine of 1945, a little-known calamity that played a big role in establishing the Communists’ moral legitimacy in the countryside. The author contends that while bad weather and a population boom certainly made the food-security situation tricky, mass hunger could have been avoided if the Vichy French and the Japanese had been less avaricious—and had the Americans realized that their bombing campaign would make any relief efforts impossible. The sum-up:

Even if Tonkin had become increasingly dependent upon imports of Cochinchina rice over the previous two decades, France can hardly be blamed for the demographic increase in the north. Assessing responsibility for the famine is further complicated by the US recourse to bombing in Indochina that often did not discriminate between civilian and military targets. In fact, the Americans were warned by the French of the consequences of destroying dikes in the north. Finally, there remains the difficulty in interpreting the willful destruction of rice stocks at war end by the Japanese military.

It is nevertheless clear, however, that continued heavy rice requisitions demanded by the Japanese and implemented by the Vichy French in a situation of administrative breakdown and even semi-anarchy after the Japanese coup, magnified the impact of the disaster. Human failure and agency combined to betray the people of northern and north-central Vietnam. Affirming perhaps the more general thrust of Amartya Sen’s arguments about the causes of famines, food distribution mechanisms broke down not in a situation of absolute scarcity as in some conflict situations but in an environment in which all signs pointed to the urgent need for surplus rice to be moved north from the Mekong delta. More than that, more rational and humane policies directed at northern Vietnam would have seen more land under rice cultivation, less rice diverted to industrial alcohol, etc., corn and other crops planted and reserved as a backup, reduction of rice exports under shortage conditions, fewer forced deliveries, greater availability of food crops in the marketplace, and the rational and humane use of stockpiled rice.

I’m still on the fence as to whether it can be categorically asserted that all famines are entirely preventable. But it’s clear that some of the worst famines in recent history were, indeed, tragedies that could have been averted had a scrap more attention been paid to such matters as logistics and basic economics. Had such care been paid to Vietnam in 1945, the nation’s postwar fate would likely have been very different.

→ 2 CommentsTags:economics·famine·France·Japan·Vietnam·Vietnam War·World War II

Monroe

January 31st, 2011

In transit back from a Now the Hell Will Start reading in Monroe, N.C.—birthplace of Herman Perry, the book’s main character. More tomorrow; in the meantime, check out the above—a tribute to Teddy Weatherford‘s heyday in Calcutta, when “The Seagull” starred at the Grand Hotel. It’s the handiwork of close pal and fellow traveler Susheel Kurien, who’s currently putting together a movie about the hidden history of Indian jazz.

→ 2 CommentsTags:Calcutta·India·jazz·North Carolina·Now the Hell Will Start·Teddy Weatherford

Over There

January 24th, 2011

I’m guesting over at Ta-Nehisi Coates‘ Atlantic blog this week, so please pop over there for your daily dose of Microkhan. I’ll cross-post at some point, but probably not ’til week’s end—just too busy doing last-minute debugging on the Teddy Weatherford tale.

Comments Off on Over ThereTags:housekeeping

Flying with the Seagull

January 21st, 2011

I wasn’t going to start plugging my next major project ’til next week, as it won’t be going live ’til Wednesday the 26th. But this piece sort of blew our cover, plus a pending guest shot over at Ta-Nehisi Coates‘ blog threatens to complicate matters, so I’ve decided to end the week with a not-so-hard sell.

What I’ve got cooking is difficult to describe: a multimedia non-fiction story about a child coal miner who became the most famous jazz musician in Asia during the ’30s and ’40s. It will initially be available in one of two ways—for iPads and iPhones through The Atavist‘s app, or as a Kindle single. If you have the hardware, I highly recommend the tablet version, which I’ve been carefully vetting these past few days. It really is a whole new form of storytelling, enriched by images, music, and hypertext that dead-tree publications can’t possibly hope to provide. This is about as close as us writers can get to cinematic without actually employing a 35mm camera.

I’ll have plenty more details to share around the 26th, including the backstory of how the piece came together, plus thoughts about what this all means for the future of my chosen trade. For the moment, though, let me just leave you with two snippets from the tale, starting with a note from the chapter simply entitled “Chicago”:

The era’s most outlandish anti-jazz screed appeared in the normally tame Ladies Home Journal, which lambasted the music as outright barbaric: “Jazz originally was the accompaniment of the voodoo dancer, stimulating the half-crazed barbarian to the vilest deeds. The weird chant, accompanied by a syncopated rhythm of the voodoo invokers, has also been employed by other barbaric people to stimulate brutality and sensuality. That is had a demoralizing effect upon the brain has been demonstrated by many scientists.”

And secondly, a somewhat context-free line culled from a chapter describing the decadence of prewar Shanghai:

Their sexual abandon had predictible consequences: Band members paid frequent visits to one Dr. Borovika, a former German fighter pilot turned physician who was a master of treating venereal diseases.

More next week, for sure. But don’t worry, I’ll also be feeding y’all posts about chess hustlers, dumb criminals, and North Korean card stunts. Microkhan always aims to please.

Update And just in case you’re most interested in the turn-of-the-century coal-mining angle, well, here you go.

→ 2 CommentsTags:Chicago·jazz·music·Shanghai·Teddy Weatherford·The Atavist·writing

The Rickshas Tell All

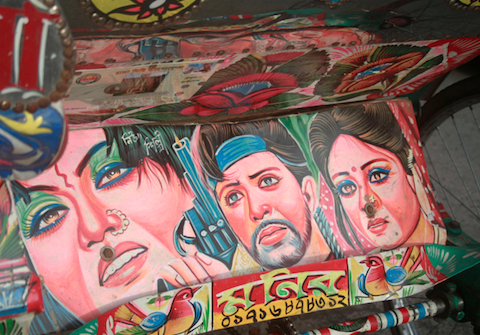

January 20th, 2011

I’m a big fan of the theory that the key to understanding societal shifts is to pay close attention to the art of the everyday. A Chinese politician who may or may not have been Deng Xiaoping is credited with summarizing this logic during the sunset of Mao Zedong’s reign, when he was asked to comment on the import of Beijing’s omnipresent wall posters: “If one knows the nuance, the walls tell all.”

Several months back, I copped that line for a post about the supposed wisdom contained in bathroom graffiti. Today I turn Microkhan’s attention to a far more gorgeous art form: the festooning of rickshas in Bangladesh. Joanna Kirkpatrick, the West’s leading authority on the matter, argues that observers of the teeming South Asian nation would be well-advised to note trends in ricksha art:

Ricksha arts flow with the times, and what one sees on many of the vehicles often reflects current political passions or conflicts. Widespread decoration of rickshas began during the separation from Pakistan, when the doyen of ricksha artists in Dhaka, R.K. Das, began portraying battle scenes. Many rickshas of that era bore paintings of Mukti Bahini fighters in action. Others simply showed scenes of air or sea combat, the new Bangladeshi flag, or animals in combat.

Ricksha decoration continued, with one fad following another: first movie scenes, then birds on every panel, then fantastic Himalayan landscapes, animal fables, and futuristic city scenes with crisscrossing aerial roadways, complete with rushing trains, buses, minivans and stretch limousines, usually colored bright red. (Lately, compact cars have begun replacing the limousines in such scenes.)

Kirkpatrick adds here that a trend of more recent vintage is rickshas that celebrate jihadism—surely a worrying trend in a nation with the world’s fourth-largest Muslim population.

(Image via this fantastic gallery)

Comments Off on The Rickshas Tell AllTags:art·Bangladesh·transportation

Hocus Pocus

January 19th, 2011

Should you ever find yourself digging through the Vanuatuan penal code, you might notice a curious offense listed in Section 151: “No person shall practice witchcraft or sorcery with intent to cause harm or detriment to any other person.” Though this prohibition obviously has its roots in traditional Vanuatuan culture, it’s inclusion in the nation’s official statutes is of far more recent vintage: The penal code was crafted in 1981, just a year after Vanuatu gained its independence.

The criminalization of witchcraft seems dreadfully archaic to my American ears. But writing in the LAWAISA Journal, the Australian legal scholar Miranda Forsyth makes the case that such a ban is actually smart policy:

There are a number of factors that indicate that the practice of sorcery should continue to be criminalised in Vanuatu. Sorcery is considered to be a serious crime by the majority of the population and as discussed above is a source of considerable community disorder and fear. As the Papua New Guinea Law Reform Commission observes “[w]hat is important about the existence of sorcery is not that it can be proved objectively and mathematically, but rather that the subjects and the objects of sorcery believe it exists and is effective, for good or for ill.” Further, the criminal law has always recognised through the doctrine of attempt that a person who intends to harm someone but is stopped before they actually cause harm is just as guilty as someone who actually causes the harm. Given that legitimacy is a major issue for the state legal systems in Melanesia, effectively criminalising behaviour widely perceived to be evil would certainly be a step in the direction of giving ownership of the state system to the people…Finally, if sorcery is not criminalised then people who honestly believe that they are the victims of sorcery will have nowhere to turn and may as a consequence engage in vigilantism. It would appear to be manifestly unfair for a legal system to provide no means of redress for a person who believes his or her life is at risk, but then to punish that person if he or she takes steps to protect themselves from that risk.

Forsyth adds that Section 151 is almost entirely for show, as there has never been a successful sorcery prosecution in Vanuatuan state courts. (The “customary” courts that exist on the village level are apparently a different story, however.)

Reading about Vanuatu’s symbolic anti-witchcraft stance made me curious about when and how similar laws slid off the books of Western nations. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the pattern was similar: Sorcery remained technically illegal long after state legal systems stopped caring about such “crimes”:

The formal decriminalization of witchcraft had little bearing on the broader process of decline that we have been discussing. The blanket repeals that took place in Great Britain and Sweden had no effect whatsoever on witchcraft prosecutions in those countries because the last trial had long preceded the legislation effecting the change. The same could be said of the large number of states which repealed their laws only in the nineteenth century. Even in those countries which passed witchcraft statutes before the end of the trials, the new laws had only a limited effect on the volume of prosecutions. The first of these laws, the French edict of 1682, probably prevented prosecutions only in the few outlying regions of the country where trials were still taking place. The same could be said of Frederick William I’s edict of 1714, since prosecutions in Prussia had slackened considerably since the 1690s. The Polish law of 1776 affected only those isolated villages like Doruchowo where there was still pressure to prosecute.

The lesson here? Laws are often the carts behind the horses. Real-world attitudes develop too quickly for the machinery of government to keep pace, something that smart officials recognize by stretching (or ignoring) the rules in place. Were legal originalism to always reign in day-to-day practice, the world would be a much more unbearable place.

(Image via Sense and Sensibility)

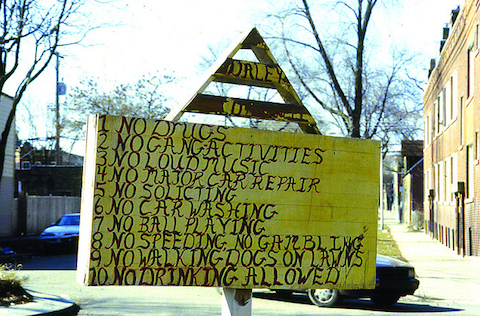

House Rules

January 18th, 2011

Got lots of good stuff lined up for the coming days, including posts about syphilitic composers, porcine economics in the New Guinea highlands, and the latest in ostrich ranching technology, to name just a few. And I’ll be moving the show over to Ta-Nehisi Coates‘ space at The Atlantic next week, so keep an eye peeled for that. But I need to be quick for today, as I’m vetting the almost-final version of my upcoming Jazz Age yarn, plus prepping for a big meeting ’bout the next major project. So content yourselves today with a peek at Chicago block club signs, loving collected by the good folks over at Temporary Services. You probably know TS best for their awesome work in documenting the technical ingenuity of inmates, but they’ve also done an admirable job of chronicling the ways in which Americans, Mexicans, and Slovenes save parking spaces and erect basketball hoops. It takes a special kind of genius to realize that this sad plank deserves to be immortalized in bits.

Comments Off on House RulesTags:art·basketball·Chicago·Temporary Services·urban decay·urban design

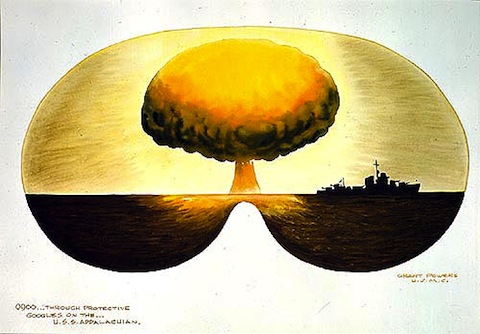

How to Wreck a Nice Atoll

January 14th, 2011

Followers of Microkhan’s microblog may have noted that I’ve developed a recent fascination with World War II-era combat art, which was created as part of an official War Department program to depict the conflict in oils, inks, and water colors. Once the the war was over, the painting continued as the U.S. speedily developed its nuclear weapons program, most notably by conducting atmospheric tests in the South Pacific. Three Naval artists were commissioned to record the destruction of Bikini Atoll in 1946; their work is now collected here.

The artists captured not only the ethereal beauty of the mushroom clouds, but also the damage wrought upon the ships that were placed in the explosions’ paths. Notably lacking from the collection? Any sense of the human toll caused by the evacuation of Bikini Atoll. We only get one glimpse of an abandoned village, where intact longhouses stand adjacent to a fluttering American flag. And then a painting of American military personnel at play. Yet there is a hint of malice to these paintings, a sense that the artists knew that they were bearing witness to events that would have unforeseen repercussions. There is no triumphalism in these artworks, only quiet awe.

More thoughts on the collection here, from a blogger with a keen interest in mushroom cloud kitsch.

→ 3 CommentsTags:art·atomic testing·Bikini Atoll·nuclear power·World War II

Blaming the Better Half

January 14th, 2011

I’ve spent a fair chunk of the morning immersed in the goings-on in Tunisia, where embattled President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali is rapidly losing his grip on power. What strikes me most about the protests is the fact that so much rage has been directed at Ben Ali’s wife, the former Leila Trabelsi, a onetime hairdresser who has leveraged her marriage to greatly benefit her family’s fortunes. Tunisia’s opposition has targeted her as a symbol of everything that has corroded their nation’s political culture: cronyism, nepotism, outright greed. While Hell might have no fury greater than a woman scorned, a frustrated public’s anger at a spendthrift quasi-dictator’s life surely comes in a close second.

I’ve spent a fair chunk of the morning immersed in the goings-on in Tunisia, where embattled President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali is rapidly losing his grip on power. What strikes me most about the protests is the fact that so much rage has been directed at Ben Ali’s wife, the former Leila Trabelsi, a onetime hairdresser who has leveraged her marriage to greatly benefit her family’s fortunes. Tunisia’s opposition has targeted her as a symbol of everything that has corroded their nation’s political culture: cronyism, nepotism, outright greed. While Hell might have no fury greater than a woman scorned, a frustrated public’s anger at a spendthrift quasi-dictator’s life surely comes in a close second.

The vilification of Ben Ali’s wife harkens back to a brief period in the mid-1980s when two of her predecessors helped cause their husband’s political demises. There was Imelda Marcos and her shoe collection, of course, but the character I find more fascinating is Michèle Duvalier. One of the most iconic photojournalism images of my youth was that of Mrs. Duvalier and her portly, slow-witted husband driving to the Port-au-Prince airport in a silver BMW, so they could flee the country just ahead of the mobs who would surely have caused them great harm. As in contemporary Tunisia, the public had had enough of the First Lady’s covetousness:

Michèle always loved money, but in the first two years of her marriage, she spent a good bit of it on the needy. Her Michèle B. Duvalier Foundation supported hospitals, clinics and pharmacies, and she made frequent inspections to ensure that they operated efficiently. But Michèle’s largesse soon took a bizarrely baroque turn. She would appear on TV dressed to the nines, handing envelopes of money to the indigent. And her attire bloomed garishly. “I remember her all in silver—and this for a 5 o’clock reception,” sniffs one stylish Haitian. Another comments, “She had too many things, and she thought she had to wear them all at once. It was a delirium she was in all the time.” The delirium got worse. “She would buy truckloads of dresses from Valentino. She had Boucheron, the Paris jeweler, fly to Haiti to sell jewels to her—not $200,000 worth but millions, millions,” says a Haitian socialite. Another friend tells of buying dozens of pairs of $500 Susan Bennis Warren Edwards shoes for Michèle during a shopping foray on Park Avenue. “She wore earrings that looked like lanterns,” says Suzanne Seitz, a Port-au-Prince hotel owner.

A country may grumble loudly at a dictator’s corruption and self-enrichment, but it simply won’t countenance having its nose rubbed in this sad fact by the wastrel who shares his bed. Since President Ben Ali didn’t understand that, perhaps he’ll soon be bound for the Tunis airport under cover darkness. Though I very much doubt he’ll be driving his own car, à la Baby Doc.

Update Annnnnddddd…he’s gone. Shouldn’t be long before his minions show up at various Swiss banks, with withdrawal slips in hand.

→ 3 CommentsTags:corruption·dictatorship·Haiti·Leila Trabelsi·Michele Duvalier·politics·Tunisia

The Importance of Good Design

January 13th, 2011

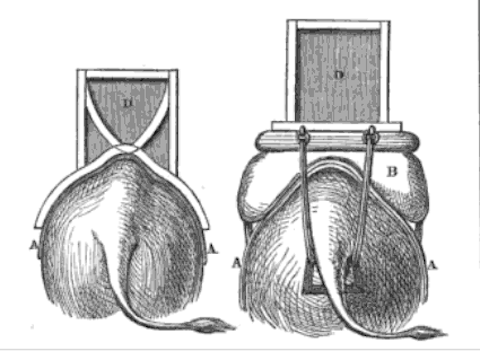

A salient reminder that engineering details really matter, from the august (and 141-year-old) pages of The Field Quarterly Magazine and Review:

The Hindustani howdah often requires six men to place it on the elephant’s padded back. The Siamese “shing kha” can be easily lifted by two persons, and this while the elephant is standing—a great advantage, especially on stony ground. The difference of weight also is such, that a Burman or Siamese elephant is comparatively fresh when the heavily caparisoned Bengal animal is quite done up for the day. All this difference, to the advantage of the shing kha, arises simply from its being made on the principle of the saddle tree, and so fitting home to the sides of the elephant’s back; whereas the howdah, being built on a flat frame, rests balanced on the animal’s vertebrae, and has to be propped and cushioned on each side of that ridge. The preceding diagram shows clearly enough the superiority in lightness and tenacity of the former vehicle as compared with the latter.

It will take a great student of Asian military history to comment on whether this design advantage somehow influenced the diverging fates of India and Thailand once European colonialists turned their eyes eastward. But if the stirrup can be credibly credited with making the Mongol Empire possible, it’s no great stretch to think that the shing kha helped shape Thailand’s political fortunes to some extent. Seemingly minor technological advantages can have profound impacts over time.

Comments Off on The Importance of Good DesignTags:British Empire·elephants·engineering·gadgets·Genghis Khan·howdahs·India·technology·Thailand·transportation

Where the Gaudy Wheels Went

January 12th, 2011

I’m a few months late in noting a milestone in American cult history: the 25th anniversary of the collapse of the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh‘s commune in Oregon, after his followers’ unsuccessful attempt to tilt a local election by tainting some local salad bars. Though I was still in grade school when this all happened, I have vivid memories of the 60 Minutes exposé that showed the commune’s orange-clad denizens lining up to greet their leader as he trundled by in one of his 90-odd Rolls-Royces. Even at that young age, I could tell that something was amiss. The residents of Antelope, the Oregon town that Rajneesh’s disciples tried to take over, certainly agreed; they considered the cultists to be invaders, and celebrated the commune’s disintegration in a fashion typically reserved for military triumphs.

When the cult finally did fall apart (at least on these shores), there was plenty of detritus to sift through. As the trailer for the Swiss documentary Guru makes clear, the Oregon commune boasted considerable stockpiles of both cash and weapons; the settlement’s police, euphemistically known as the “Peace Force,” all brandished late-model Uzis, for example. But the Bhagwan’s most visible asset was his Rolls-Royce collection, and it became an object of desire for a Dallas auto dealer named Bob Roethlisberger—as well as a footnote in the massive savings and loan crisis of the 1980s. An old Texas Monthly story has the goods:

Three days before Thanksgiving of 1985, Dallas luxury-car dealer and Sunbelt Savings client Bob Roethlisberger landed in a private jet at Rancho Rajneesh, Oregon. The ranch was home to the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, and Roethlisberger had come to the remote desert community to buy more than seventy cars from the Bhagwan’s Rolls-Royce collection. It would be a difficult deal to finance, because the final sticker price for that many exotic cars would run into the millions. Selling the cars would be equally difficult once they were purchased; 36 of them had been painted by one of the Bhagwan’s staff artists, designed with peacocks and geese in flight and decorated with two-toned metal flake and cotton bolls. That many luxury cars painted in that way would be hard for any market to digest. But Roethlisberger bought 84, and the deal was financed with a note of more than $6 million from a wholly-owned subsidiary of Sunbelt Savings.

Roethlisberger did manage to sell a fair number of the cars, but not nearly enough to pay back his debt obligations. (He died in April 1986, at the age of 40.) Among the vehicles he was unable to unload was a green-and-gold-lace number with teargas guns secreted beneath the fender. Here’s to hoping that it would up in the hands of someone who could appreciate its bizarre lineage.

And by the way, if anyone knows how I can see Guru here in the States, please advise. I’m especially keen to hear the tale of the former Ma Anand Sheela (now Sheela Birnstiel), who was either the Bhagwan’s Lady Macbeth or his convenient scapegoat. She now runs a couple of nursing homes in Switzerland, which is presumably how the Swiss filmmakers got access to her.

→ 10 CommentsTags:1980s·Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh·cars·cults·finance·Guru·movies·Oregon·Rolls-Royce

Crumbs on the Table

January 11th, 2011

Running late on a monthly deadline, plus putting the finishing touches on the soon-to-drop Jazz Age yarn. Back tomorrow with some commentary on gang life in Port Moresby. Or perhaps some commentary on the mystery of Ma Anand Sheela.

A Disease of Special Knowledge

January 10th, 2011

My line of work has brought me in contact with more than a few schizophrenics over the years, both as story subjects and as correspondents. I’ve become quite familiar with the seemingly impenetrable logic by which such people try to make sense of the world, and how their off-tangent worldviews occasionally lead to the commission of terrible acts. I have great sympathy for those who are cast adrift in their own delusions; as the schizophrenic mathematician John Nash once observed, the men and women who suffer from this disease do not view themselves as ill, but rather as lucky souls who’ve been blessed with “special knowledge” about the world.

My line of work has brought me in contact with more than a few schizophrenics over the years, both as story subjects and as correspondents. I’ve become quite familiar with the seemingly impenetrable logic by which such people try to make sense of the world, and how their off-tangent worldviews occasionally lead to the commission of terrible acts. I have great sympathy for those who are cast adrift in their own delusions; as the schizophrenic mathematician John Nash once observed, the men and women who suffer from this disease do not view themselves as ill, but rather as lucky souls who’ve been blessed with “special knowledge” about the world.

I though of Nash’s quote while trying to process Saturday’s tragic events in Tuscon, which were obviously the handiwork of a schizophrenic young man. Vast seas of digital ink have been spilled in an effort to identify Jared Lee Loughner’s politics, but I think that’s ultimately a mug’s game. He appears to have much less in common with past political assassins than he does with Nathan Gale, the schizophrenic former Marine who killed the great guitarist Dimebag Darrell Abbott in 2004. The motives of both killers will never truly make sense to the rest of us, because we will never have first-hand access to the deluded realms in which these two men lived. Gale, for example, had a fixation on Abbott, to the point that he believed that the musician was stealing lyrics out of his brain. My hunch is that Loughner’s motives, if they’re ever wholly revealed, will be similarly nonsensical—though not, of course, to him.

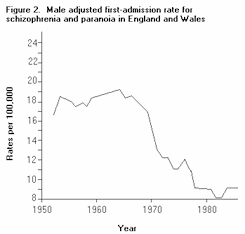

Rather than sift through Loughner’s screeds in search of political clarity, my first research impulse was to look into the historical prevalence of schizophrenia. I wondered whether the Tuscon tragedy was a harbinger of things to come, a sign that incidents of schizophrenia-related violence might soon be on the ascent. But my hypothesis looks to have been way off base; diagnoses of schizophrenia have actually been plummeting in the Western world, despite greater awareness of the disease’s symptoms. This paper makes the argument that better care before and during childbirth has made a huge statistical difference:

Obstetric complications are related to the subsequent development of schizophrenia, the risk for people born with complications being two to three times greater than that for people born without. Complications of delivery, rather than of pregnancy, are more likely to occur with increased frequency in schizophrenia samples; and oxygen deprivation, especially owing to prolonged labor, appears to be the common denominator among these complications. In four studies cited by McNeil (1988), prolonged labor occurred in 17 to 40 percent of schizophrenia samples compared with 8 to 19 percent of control subjects.

Yet schizophrenia is an ancient disease, and one we’re unlikely to ever excise through mere obstetric caution. Attention must be paid, then, to those most at risk for the malady—and, curiously, that often means migrants in big cities:

A coherent and consistent body of research has emerged in recent years demonstrating that migrants have an increased risk of schizophrenia. Two recent systematic reviews have confirmed that migrants have a significantly increased risk of developing schizophrenia (approximately

a three- to fivefold risk ratio)…Several high-quality studies have indicated that those born in cities have approximately a twofold increased risk of developing schizophrenia, compared to those born in rural regions. As a large proportion of individuals

in the developed world are born in cities, the population-attributable fraction for this exposure is substantial (about 30%). A systematic review recently

reported that those living in cities also had significantly higher incidence rates of schizophrenia compared to those living in mixed urban–rural sites.

The bottom line is that someone needed to step in and get Loughner the treatment he so obviously needed. But as was the case with Nathan Gale, no one seemed to recognize that a man who claims to be in possession of “special knowledge” can become a monster—even though, in his own eyes, he is simply acting as nature intended.

→ 7 CommentsTags:Jared Lee Loughner·medical history·medical science·public health·schizophrenia

Cindy’s Dreadful Second Act

January 7th, 2011

For the year’s first installment of Microkhan’s much-beloved Bad Movie Friday feature, I was sorely tempted to call out Cindy Crawford’s disastrous attempt to evolve from model to mactress: 1995’s Fair Game, not to be confused with the recent Plame Affair dramatization of the same name. But I decided to shift course upon reading Crawford’s credits and realizing that she actually went to the feature-film once more after Fair Game‘s flop—though she did have the good sense to do so overseas. The not-so-pretty result was Guardie del copo (Bodyguards), a slice of Italian slapstick that (to be charitable) doesn’t quite translate. The clip above reels off a succession of the film’s key pratfalls; a more salacious trailer can be found here, and should only be played if you’re in a place where gratuitous semi-nudity won’t get you fired.

You can also do a close read on Crawford’s dubbed-in acting chops by watching this clip. To her credit, I kind of like the way she reels off the proper noun “Napoli.” And I have to surmise that this movie does a surprisingly good job of summarizing the trashy aesthetics of Berlusconi-era Italy—a topic thoughtfully explored in 2009’s Videocracy (also NSFW, alas).

Comments Off on Cindy’s Dreadful Second ActTags:Bad Movie Friday·Cindy Crawford·Guardie del copo·Italy·movies·Silvio Berlusconi

No Sense of Time

January 6th, 2011

I’ve recently taken a lot of comfort from this Paris Review Q&A with John McPhee, in which the non-fiction master confesses that his writing remains a day-to-day struggle. (Celebrities—just like us!) But while most of the interview is dedicated to the creative process and the occasional madness it engenders, there is also this dead-on snippet about what McPhee learned from hanging out with geologists for a series of books (now collected as Annals of the Former World):

There’s a line in the book: “If you free yourself from the conventional reaction to a quantity like a million years, you free yourself a bit from the boundaries of human time. And then in a way you do not live at all, but in another way you live forever.” And I certainly developed this sense of time. I was fascinated by the intersection of human time and geologic time…The fact is that everything I’ve written is very soon going to be absolutely nothing—and I mean nothing. It’s not about whether little kids are reading your work when you’re a hundred years dead or something, that’s ridiculous! What’s a hundred years? Nothing. And everything, it doesn’t evanesce, it disappears. And time goes on, and the planet does what it’s going to do. It makes you think that you’re living in your own time all right. It makes the idea of some kind of heritage seem touching, seem odd.

I couldn’t help but think of McPhee’s dose of perspective while reading this account of the Cameroonian elite’s campaign against pidgin, the use of which is discouraged on many university campuses. the sign at the top of this post is part of a campaign to get Anglophone students to stop speaking pidgin, lest they fail to attain their promise in life:

The underlying message is a fairly simple one: In order to fit in, English-speaking Cameroonians must shun their inferior culture and language(s) which are obstacles to their integration into the national (read Francophone) mainstream, and gravitate towards French which is the language of access, success and power. Pidgin in particular is therefore portrayed as a language of confinement (in the “Anglophone Ghetto”), of exclusion (from “national mainstream”) and of inferiority (vis-a-vis the French language).

Yet this elitist campaign only reveals its orchestrators’ ignorance of the true nature of time. Do they not realize that English was once considered a sort of pidgin, a mishmash of northern European dialects that was spoken by a conquered class subordinate to a French-speaking elite?

Language, like the tectonic plates that shift beneath our plates, is a fluid thing. And though its shifts may be imperceptible to those who cannot see beyond their own lifespans, it is always fated to evolve into a melange of various sources. In that way, pidgin is actually quite futuristic—a glimpse of what might happen as English spreads and mutates after coming in contact with thousands of local dialects.

More Microkhaning on the history of pidgin here.

→ 1 CommentTags:Cameroon·geology·John McPhee·language·philosophy·pidgin·writing

The Sound of St. Georges Cross

January 5th, 2011

Major projects day here at Microkhan HQs, which means lots of reading up on Eldridge Cleaver’s interest in juche and cold-calling retired Naval officers. I trust that you can get through the next 24 hours with the aid of MC Soom T, one of Glasgow’s finest songstresses. Full interview here if you’d like to learn more about her (and have a knack for understanding Scottish accents).

Comments Off on The Sound of St. Georges CrossTags:dancehall·MC Soom T·music·Scotland

Cancer Sticks in the Clink

January 4th, 2011

One of my favorite economics story of the millennium is the Wall Street Journal‘s 2008 A-head about the use of tinned mackerel as prison currency. It’s a fantastic testament to the primacy of money; even when removed from ordinary society, humans always find a way to regulate their commerce by creating tangible symbols of achievement. When I initially read the piece, I could only think of the cover of the Federal Reserve’s infamous (but strangely awesome) The Story of Money comic book. The four-paneled illustration seems to be making the argument that bartering is a relic of our cavepeople past, and that currency is a hallmark of civilization.

The mackerel story surprised because it seemed to illustrate a shift in prison economics akin to America’s changeover from the gold standard. Cigarettes have traditionally been the currency of choice for the incarcerated, partly because, when push comes to shove, such “money” can be consumed like a commodity. The mackerel can, too. at least in theory, but the inmates would prefer not to; the WSJ makes clear that the fishy treat is universally unbeloved in prison, and so the vast majority of cans are never popped open.

Mackerel became money after prisons started cracking down on tobacco use, but cigarettes have by no means disappeared as a form of alternative currency. The bans have simply pushed the cigarette trade deeper underground, as explained in Smoke ‘Em If You Got ‘Em: Cigarettes in U.S. Prisons and Jails. The paper points out that cigarettes, like gold bullion in the outside world, remain a highly prized fallback currency because, presumably unlike mackerel, they have great value beyond their functional role in the prison economy. And the official crackdown on tobacco has forced inmates to engage in riskier behavior in order to maintain their “wealth”:

Just as the criminalization of cocaine and heroin gives rise to impure drugs and a scarcity of sterile drug paraphernalia, cigarettes sold on the black market are often more harmful than those sold legally and are combined with less healthy smoking practices. For instance, because rolling papers were scarce, some inmates resorted to rolling tobacco with toilet paper wrappers or with pages from a Bible. Both contain ink or dyes that are harmful when burned. Also, inmates reported removing the filters on manufactured cigarettes to increase the potency of each drag of tobacco. Furthermore, inmates who might otherwise have smoked a lower tar cigarette had little choice but to smoke higher tar cigarettes.

I’d love to have a moment to calculate the health-care costs associated with the outlawing of tobacco in American correctional facilities. My hunch is that prison officials would be better advise to regulate the market, given that bootleg cigarettes may cause long-term health problems that may eventually become the government’s burden. Is there a lesson to be learned here about drug policy in the world outside the prison walls?

Update Edited this post to get rid of numerous logic and grammatical errors. Sorry, just getting back into the swing after the holidays. As a token of penance, check out this great photo of Tajik goat polo.

→ 7 CommentsTags:cigarettes prisons·comics·drugs·economics·The Story of Money·Wall Street Journal·War on Drugs

Bowled Over

January 3rd, 2011

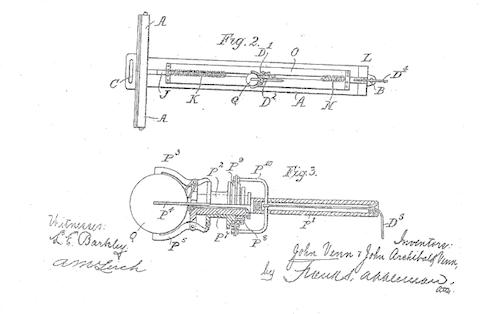

Let’s begin the year by hailing the ingenuity of a man who has contributed much to both mathematics and Internet meme-ry: John Venn.

Venn is, of course, best known for concocting the elegant diagramming system that now bears his name. Aside from elucidating the fundamentals of logic for generations of schoolkids, Venn diagrams have also provided structure for countless middlebrow-brow jokes. For this achievement alone, Venn deserves a place in the organizational pantheon alongside Melvil Dewey and Edwin G. Seibels.

But Venn was far from a one-trick pony, nor one who confined his genius to the realm of the theoretical. He was also quite the engineer, and used his tinkering skills to create one of the earliest mechanical robots: a cricket bowling machine that was sort of the Deep Blue of its day and sport. The machine was rumored to have bested the top batsman on the Australian national team, largely because of the way it created baffling break.

What’s odd is that, despite the early hype over the machine’s ability to best human players, Venn’s cricket bowling contraption was quickly relegated to the status of training device—quite like the Jugs machines that now dominate the market. I, for one, would like to see a revival of the engineering race to design a machine capable of stumping the world’s best batsmen. I can only guess that this quest was abandoned once humans adjusted to the machines’ limited trickery. But I refuse to believe that machines can only triumph over humans in contests of mental acuity. At some point, the robots will prove that they can triumph in the athletic arena, too. How long will that take? The answer might depend on how much human competitors are willing to modify their bodies to keep their edge.

→ 6 CommentsTags:cricket·John Venn·mathematics·robots·sports