June 16th, 2013

Less than 48 hours to go ’til The Skies Belong to Us officially drops, which is why I’m spending Father’s Day locked in the yurt, endeavoring to spread the good word. You can aid the cause by checking out this enthusiastic review from The New York Times, in which the book is described as “such pure pop storytelling that reading it is like hearing the best song of summer squirt out of the radio.”

Less than 48 hours to go ’til The Skies Belong to Us officially drops, which is why I’m spending Father’s Day locked in the yurt, endeavoring to spread the good word. You can aid the cause by checking out this enthusiastic review from The New York Times, in which the book is described as “such pure pop storytelling that reading it is like hearing the best song of summer squirt out of the radio.”

Sound like your kind of thing? Or simply appreciative of all the Papua New Guinea coverage I’ve brought you over the years? Please consider snagging a copy. I promise you won’t regret it.

Tags:books·The New York Times·The Skies Belong to Us

June 10th, 2013

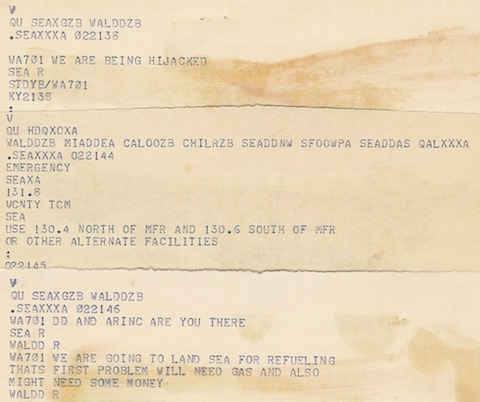

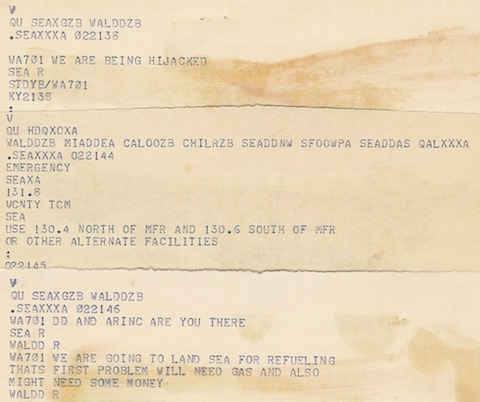

Just eight days to go until The Skies Belong to Us goes live, a fact that explains my recent absence ’round this particular corner of the digital steppe. I’ll be popping up this week, though, to offer some Skies-related goodies, including a limited-edition set of skyjacker trading cards. In the meantime, check out the footage above from the 1961 hijacking of Continental Airlines Flight 54, a landmark episode that I also discuss in today’s Slate installment of “Skyjacker of the Day.” If anyone knows what became of Cody Bearden after his 21st birthday, please advise.

Tags:The Skies Belong to Us

May 14th, 2013

Granted, I haven’t posted in a whopping eleven days—the longest dry spell in Microkhan history. But rest assured, I have not abandoned this endeavor after a measly 1,559 entries. I have just been so engulfed with the pregame for The Skies Belong to Us, as well as a pair of absorbing Wired projects, that I’ve scarcely had a spare moment to notice that the Grand Emprette has now mastered the art of sitting up, let alone keep pace with this site. I’ll try my best to improve my performance between now and the book’s June 18th launch, but please understand that we’re dealing with extraordinary circumstances over here; things may be more sporadic than any of us might wish.

I’ll try and give you reason to keep checking in, though, by promising to hold some giveaways of limited-edition skyjacker trading cards. Gimme a week or so to come up with a tough-enough trivia question, and we’ll go from there.

Tags:Belinda Bedekovic·keytar·music·The Skies Belong to Us

May 3rd, 2013

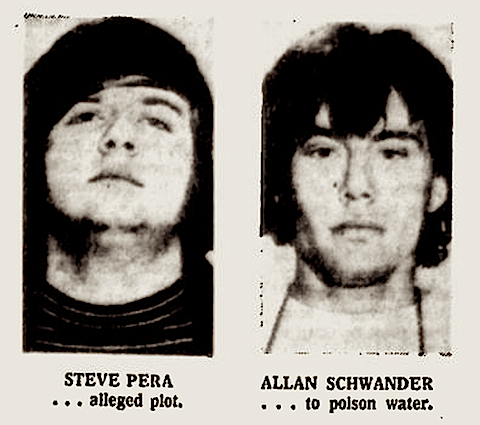

The two young men above once dreamed of committing a truly dreadful act: poisoning Chicago’s water supply, in order to kill millions and further the ambitions of their revolutionary organization, R.I.S.E. Mainstream press accounts of their failed caper describe them as incompetent fools, but this case study gives them credit for developing some biological agents that at least had the potential to cause grave damage. More important, the case study delves into the specifics of the duo’s motives, which could only have been concocted during a drug-fueled bout of sexual frustration:

The two young men above once dreamed of committing a truly dreadful act: poisoning Chicago’s water supply, in order to kill millions and further the ambitions of their revolutionary organization, R.I.S.E. Mainstream press accounts of their failed caper describe them as incompetent fools, but this case study gives them credit for developing some biological agents that at least had the potential to cause grave damage. More important, the case study delves into the specifics of the duo’s motives, which could only have been concocted during a drug-fueled bout of sexual frustration:

R.I.S.E. was apparently founded in mid-November 1971. The precise meaning of the group’s name is unknown, but one police informant indicated that the “R” stood for Reconstruction, the “S” for Society, and the “E” for Extermination (the source could not recall the meaning of the “I”).

Schwandner articulated the group’s ideology in a six-page “manifesto” that he kept in a binder in his apartment…The manifesto started with an assertion that mankind was destroying itself and the planet, and that the only way to preserve the environment was for the human race to be wiped out except for a select group of people who would live in harmony with nature. According to the document, the world would be a better place if it were inhabited only by a small group of like-minded people who agreed on how to address its problems. With the ultimate aim of repopulating the planet, Schwandner planned to recruit people into the group who would select a mate of the opposite sex. He reportedly envisioned that R.I.S.E. would ultimately include sixteen people, comprising eight male-female pairs.

Once their plan was foiled, the pair fled to Cuba, where they suffered through a predictably awful spell in prison. Stephen Pera was the lucky one, in that he eventually got to return to the U.S. and get off with a light punishment. Allen Schwandner does not appear to have been so fortunate; sometimes the wages of youthful idiocy is death.

Tags:1970s·Allen Schwander·Chicago·crime·Cuba·history·psychology·Stephen Pera·terrorism

April 29th, 2013

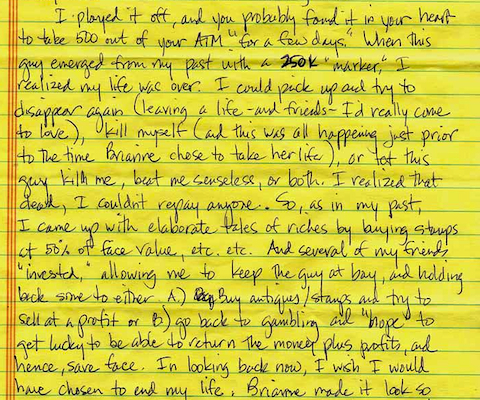

After six years on the run, con man David Scott Srail was finally nabbed at a San Antonio airport last week. His capture was due in part to the efforts of a Florida woman, Jacira Paolino, whose daughter was swindled by Srail. Since virtually the moment that Srail went on the lam, Paolino has maintained a website detailing his crimes—a site that includes a four-page handwritten letter in which the scammer unwittingly reveals the depths of his narcissism. Read the whole thing if you have even the slightest interest in the psychology of sociopaths—Srail goes to amazing lengths to make himself an object of pity, when the real purpose of the letter is to inform a victim that all is lost. The lack of conscience layered beneath the veneer of empathy is quite a wonder to behold.

After six years on the run, con man David Scott Srail was finally nabbed at a San Antonio airport last week. His capture was due in part to the efforts of a Florida woman, Jacira Paolino, whose daughter was swindled by Srail. Since virtually the moment that Srail went on the lam, Paolino has maintained a website detailing his crimes—a site that includes a four-page handwritten letter in which the scammer unwittingly reveals the depths of his narcissism. Read the whole thing if you have even the slightest interest in the psychology of sociopaths—Srail goes to amazing lengths to make himself an object of pity, when the real purpose of the letter is to inform a victim that all is lost. The lack of conscience layered beneath the veneer of empathy is quite a wonder to behold.

Tags:con artists·crime·Dave Srail·Florida·psychology

April 24th, 2013

Over on the ol’ microblog, I probably link to a half-dozen intriguing tales per day, most of which I forget about a few moments after posting. But every so often, one of the stories I toss into the flotsam sticks with me for days, even weeks, to the point that I need to sit down and figure out why it’s still occupying space in my head. Such is the case with this complex prison saga from Alaska, which centers on a guard who was fired for violating a workplace rule: he brought a pocket knife into the facility. But his violation was only discovered after he used that pocket knife to save life:

Over on the ol’ microblog, I probably link to a half-dozen intriguing tales per day, most of which I forget about a few moments after posting. But every so often, one of the stories I toss into the flotsam sticks with me for days, even weeks, to the point that I need to sit down and figure out why it’s still occupying space in my head. Such is the case with this complex prison saga from Alaska, which centers on a guard who was fired for violating a workplace rule: he brought a pocket knife into the facility. But his violation was only discovered after he used that pocket knife to save life:

When Spalding ordered inmates into lockdown, most went to their cells. One refused. “Let’s do this,” the inmate said to him, the same phrase used the day before.

Spalding figured an attack was coming and tried to leave. The inmate, a muscular 22-year-old serving seven years for robbery and assault, got between him and the door. They stared at each other. Then the inmate punched him in the head, Spalding said. Spalding tried again for the door.

“About that time, someone jumps me on the back or someone hits me from behind, I’m not sure what. But there was contact,” Spalding said.

A tornado of fighting men lurched toward the locked door. “I’m getting hit, punched, stuff like that, the whole time,” Spalding said. A third inmate joined in. “If I don’t do something now, I am dead,” Spalding remembers thinking.

He was pressed against a glass wall as he fished for his knife. “I finally get it out, I open it, I turn and then just start thrusting at anything that moved,” Spalding said.

He remembers falling to the floor. “They are putting the boots to me.”

The attack seemed to go on forever but lasted less than a minute, he said.

“One of them said, ‘Hey guys, he’s got a knife,’ ” and the inmates backed off, Spalding said. He got up. Everything was red from blood running into his eyes.

As the story makes clear, the security situation within the prison was so woeful that several guards felt compelled to carry added protection, despite knowing full well that they risked their jobs by doing so. They obviously feared for their lives more than they feared for their employment.

The question, then, is whether they had exhausted all other avenues to address their security concerns before going vigilante on the situation. At what point do we accept that people have no choice but to take the most extreme measures to protect themselves, even when those measures run contrary to established laws? There’s so much rich philosophical terrain to explore in this tale. Though for those directly involved, such questions are probably secondary to more basic issues, like when they’ll get their next paycheck.

Tags:Alaska·crime·knives·philosophy·prisons

April 19th, 2013

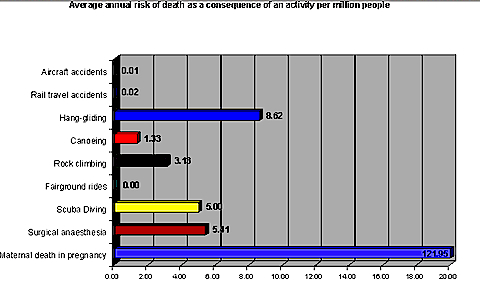

It’s a good thing I didn’t encounter this graph until after the Grand Emprette joined us here on Spaceship Earth. It’s a salient reminder that the simple act of producing life is still several times more hazardous than any thrill-seeking leisure activity, no matter how seemingly nuts.

It’s a good thing I didn’t encounter this graph until after the Grand Emprette joined us here on Spaceship Earth. It’s a salient reminder that the simple act of producing life is still several times more hazardous than any thrill-seeking leisure activity, no matter how seemingly nuts.

It’s worth noting that this graph would have an even more disturbing tilt if it wasn’t using British figures for maternal mortality; the rate in the United States is far worse. And then there’s Benin.

Tags:Benin·hang gliding·maternal mortality·public health·scuba diving·statistics

April 17th, 2013

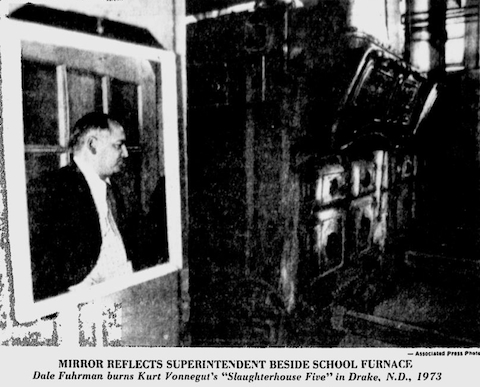

In 1973, after a student complained about the language in Slaughterhouse Five, the administration at Drake (N.D.) High School decided to take rather dramatic action (see above). When informed of what had been done to his creation, author Kurt Vonnegut responded in the appropriate manner:

In 1973, after a student complained about the language in Slaughterhouse Five, the administration at Drake (N.D.) High School decided to take rather dramatic action (see above). When informed of what had been done to his creation, author Kurt Vonnegut responded in the appropriate manner:

Vonnegut, asked for his reaction, said, “It’s grotesque and ridiculous. It’s like asking how do I feel about man-eating sharks.

Once the initial shock had worn off, Vonnegut dashed off a more eloquent letter to the offending school. It is of course to his great credit that the incident is now recalled with noticeable embarrassment by the people of North Dakota. Images of book incineration rarely, if ever, age well.

Tags:books·censorship·Kurt Vonnegut·North Dakota·sharks·Slaughterhouse Five

April 12th, 2013

The low-grade 1972 thriller Skyjacked plays a brief but important role in my upcoming book. Here’s a brief excerpt of the chapter in which I describe why this lesser Charlton Heston flick made a splash at the box office:

The film was controversial due to its subject matter, and numerous TV stations refused to run ads for it; one station manager in Washington, D.C., said he feared the movie would impel viewers with “impressionable minds” to seize planes. But Skyjacked nevertheless opened strongly at the box office, drawing moviegoers curious to experience the terror of life aboard a hijacked jet.

Despite an all-star cast that included Rosey Grier and Yvette Mimieux in addition to Heston, Skyjacked was a dreadful movie riddled with plot holes. Based on a pulp novel called Hijacked, the movie was a halfhearted whodunit in which the skyjacker initially communicates his threats by anonymously scrawling messages on a lavatory mirror. It is no great shock when the culprit is revealed to be a stereotypically frazzled Vietnam vet, played by the thirty-one-year-old James Brolin. Upset over his treatment by the Army, Brolin’s character decides to escape to the Soviet Union, where he is certain that he will be given a hero’s welcome. His daft plan unsurprisingly fails, though not until the Boeing 707 is on the ground in Moscow.

Strangely, Heston doesn’t get the honor of dispatching the traitorous Brolin. That feat is instead accomplished by (SPOILER ALERT!) the Soviet military, which rather randomly decides that this crazy hijacker won’t fit into the dictatorship of the proletariat. Brolin really should have chosen a more laid-back destination.

Tags:Charlton Heston·hijacking·James Brolin·movies·Rosey Grier·Skyjacked·Soviet Union·Yvette Mimieux

April 10th, 2013

Apologies for the sporadic posting these last couple of weeks. I’m neck deep in a million things as the book nears publication, including those all-important updates on Skyjacker of the Day. Fear not, though, this enterprise still lives, and posts shall be issuing at more traditional rate starting early next week.

For the moment, though, I’d like to direct your attention to this Utican tale of a mass-murder survivor, which delves into one of Microkhan’s favorite issues: how a brush with catastrophic death alters the soul. The protagonist of the story, a 66-year-old barber whose co-worker was killed, is obviously still coming to grips with why he was spared, and how he should proceed with the precious time he has remaining. There’s a point in the story where he flicks at the notion of karmic reward, but I much prefer the inquisitive sentiment he expresses in the kicker:

Seymour knows there wasn’t much difference between him and the other well-respected and much-loved men who died that day.

“So what saved you?” Seymour’s mother asked her son.

“He missed,” Seymour replied.

Out of the mouths of the nearly murdered, wisdom flows.

Tags:crime·murder·philosophy·religion·Utica

April 8th, 2013

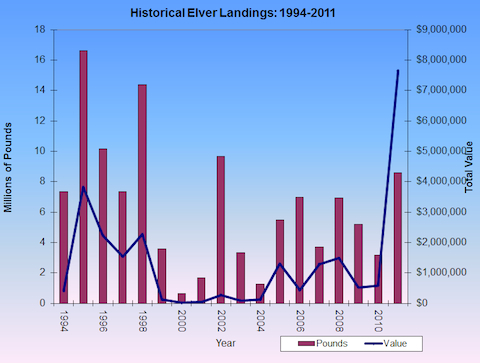

If you want to know why elver-related crime is on the rise in Maine (and elsewhere), look no further than the chart above, which shows just how valuable those wriggly little creatures have become in the past few years. As this dissection of the political tussle over fishing licenses reveals, the Asian appetite for baby eels is having a significant ripple effect on the Down East economy:

If you want to know why elver-related crime is on the rise in Maine (and elsewhere), look no further than the chart above, which shows just how valuable those wriggly little creatures have become in the past few years. As this dissection of the political tussle over fishing licenses reveals, the Asian appetite for baby eels is having a significant ripple effect on the Down East economy:

Landing records reflect the impact of market price on the size of Maine’s recent annual eel harvests. In 2008, Maine’s eel catch weighed in at 6,951 pounds, with a value of $1.5 million, or $216 a pound. By 2010, the take was down to 3,185 pounds with a market value of $585,000, or $184 a pound. Both the harvest and its value spiked in 2012 at 19,000 pounds worth $38 million at a record-high per-pound price of $2,000.

My hunch is that the elver bubble is set to pop, mostly because prices have reached the point where it makes more sense for restaurateurs to try and fool diners than buy the genuine article. What percentage of those who consume elvers at the end of the supply chain can really tell the difference between the bona fide foodstuff and a cheap imitation? Certainly far less than the warring factions in Maine might care to admit.

Tags:economics·elvers·fishing·food·Maine

April 4th, 2013

The Papuan taipan is arguably the deadliest snake in the world, but not only because of the intensity of its venom. The creature kills humans at such an alarming rate primarily because the antidote to its bite is too expensive for most Papuan medical facilities to afford. That unfortunate fact could soon change, though, thanks to research out of Costa Rica’s Instituto Clodomiro Picado, which is developing an affordable taipan antivenom called TaipanOx-ICP. This fascinating interview about the medication’s upcoming clinical trials sheds light on why creating antivenoms is such a labor-intensive exercise:

The Papuan taipan is arguably the deadliest snake in the world, but not only because of the intensity of its venom. The creature kills humans at such an alarming rate primarily because the antidote to its bite is too expensive for most Papuan medical facilities to afford. That unfortunate fact could soon change, though, thanks to research out of Costa Rica’s Instituto Clodomiro Picado, which is developing an affordable taipan antivenom called TaipanOx-ICP. This fascinating interview about the medication’s upcoming clinical trials sheds light on why creating antivenoms is such a labor-intensive exercise:

Anti-venoms are made by immunising a horse with selected snake venoms, so that the horse makes antibodies and these antibodies are extracted from the horse’s plasma and refined so that they’re fit to be given by the intravenous route to human snakebite victims. And the Costa Ricans, as I say, have found a much simpler, less expensive, but no less safe and no less effective method.

If anyone can point me toward a readable history of antivenom development, I’d be much obliged. I’d be interested to know how horses were settled upon as the ideal animals for antibody production. Were other animals tried out first, with disappointing results?

Tags:antivenom·Costa Rica·horses·medical science·medicine·Papua New Guinea·snakes

April 2nd, 2013

Perhaps because they were so enthusiastic about ritualistically slicing hearts out of their fellow humans, the Aztecs are rarely examined with much seriousness. This University of Texas collection seeks to correct that oversight, by chronicling the tenets of the legal system that sustained Aztec society until the conquistadors showed up. There is great stuff throughout, such as the bit about the Aztecs’ curious attitude toward alcohol consumption. (“Public drunkenness was punishable by death for younger individuals; however, elders could consume as much alcohol as they wished.”) My favorite part, though, deals with marital law, and includes the revelation that the Aztec definition of “traditional marriage” was rather loosey-goosey:

Perhaps because they were so enthusiastic about ritualistically slicing hearts out of their fellow humans, the Aztecs are rarely examined with much seriousness. This University of Texas collection seeks to correct that oversight, by chronicling the tenets of the legal system that sustained Aztec society until the conquistadors showed up. There is great stuff throughout, such as the bit about the Aztecs’ curious attitude toward alcohol consumption. (“Public drunkenness was punishable by death for younger individuals; however, elders could consume as much alcohol as they wished.”) My favorite part, though, deals with marital law, and includes the revelation that the Aztec definition of “traditional marriage” was rather loosey-goosey:

Marriage was conditional in that the parties could decide to separate or stay together after they had their first son. Marriages could also be unconditional and last for an indefinite period of time.

It’s fun to imagine the middle-aged dating scene in Tenochtitlan, replete with marriage vets who left the kids at home. Babysitting rates must have been through the roof.

Tags:Aztecs·law·marriage

March 29th, 2013

I’m trying to cram in a bunch of last-minute work before disappearing for the (brief) holiday weekend, so I’ll catch y’all on Monday with something about Aztec marital law. In the meantime, please check out the trailer for The Skies Belong to Us, which is the genius handiwork of Thomas Beug (of This is My City fame). And you can hear even more of my voice on this brand-new podcast, in which I discuss heavy-duty archival research, my travails in northwest Burma, and my extremely brief guest appearance on the second episode of Punky Brewster.

Tags:The Skies Belong to Us

March 27th, 2013

The Gujarati folksinger Farida Mir does not mess around when it comes to political activism. While her Western peers may content themselves with making bold statements in the media, Mir has no problem with getting her hands dirty—particularly when the lives of cows are stake. Just check out how far she recently went to protest a government plan to provide cattle to beef-eating “tribals” in her native state:

The first incident was reported near Kuvadva on the outskirts of the city Friday night when Mir and seven others stopped a truck carrying nine cows and a calf. The truck was on its way to Pavi Jetpur taluka in Vadodara district from Khambahlia in Jamnagar district. The singer and her associates allegedly beat up driver and cleaner of the truck, torn off documents of the animal transfer and vandalised the vehicle.

Mir, who is an active Gaurakshak, filed a complaint against the driver and cleaner under the Prevention of Cruelty to Animal Act 1956 at Kuwadva police station and “rescued” the cows.

You can accuse Mir of many things. But living in the celebrity bubble certainly isn’t one of them.

Tags:cows·Farida Mir·India

March 26th, 2013

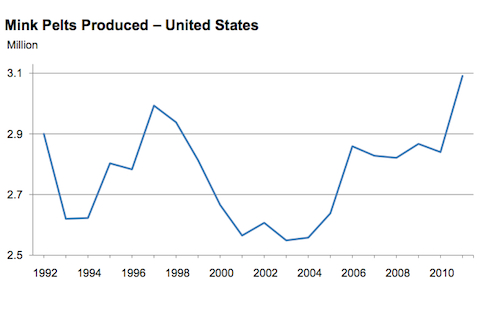

There’s no question that the animal-rights movement has successfully altered America’s attitude toward fur; coats composed of pelts are no longer a de rigueur status symbol for those with too much money on their hands. So why, then, is mink production ramping up to virtually unprecedented levels? Because the newly affluent Chinese covet fur coats to the same degree as the Eisenhower-era wives of industrial tycoons:

There’s no question that the animal-rights movement has successfully altered America’s attitude toward fur; coats composed of pelts are no longer a de rigueur status symbol for those with too much money on their hands. So why, then, is mink production ramping up to virtually unprecedented levels? Because the newly affluent Chinese covet fur coats to the same degree as the Eisenhower-era wives of industrial tycoons:

China imported nearly $126 million worth of U.S. mink pelts last year, making it the second most lucrative mink export market for American fur farmers behind South Korea, according to FAS. The North American Fur Auction, which touts itself as the largest fur wholesale auction house in North America, said nearly three quarters of the 700-plus buyers who attended its Toronto auction in February were Chinese.

Zhang Yiren, a 25-year-old medical magazine employee, tried on a fur coat in a Shanghai shopping mall recently with her parents. “I have had two fur coats and bought them for myself,” she said. “The angora one cost me 1,600 yuan ($250), and I love the style. It is beautiful and keeps me warm.”

Herein lies a difficult challenge for the animal-rights movement—namely, how do they modify their message and tactics to reach Chinese consumers? Cheeky shock tactics may not work quite as well in the Middle Kingdom.

Tags:China·fur·minks·rodents

March 21st, 2013

Non-fiction storytelling is ridiculously time-consuming. My latest Wired story, which began life as a Microkhan post in January 2012, has been in the works for nearly a year. Granted, much of that time was wasted on tasks that didn’t pan out—I’m still waiting for a certain FOIA request to come through, for example, not to mention a callback from the Kansas Highway Patrol. But there were also so many hours spent perusing over 3,600 pages of trial transcripts, and talking to people with an incredible amount at stake in the project. The end result is a story that I hope y’all will read and pass along—the tale of a creative genius who became a casualty of the War on Drugs.

Non-fiction storytelling is ridiculously time-consuming. My latest Wired story, which began life as a Microkhan post in January 2012, has been in the works for nearly a year. Granted, much of that time was wasted on tasks that didn’t pan out—I’m still waiting for a certain FOIA request to come through, for example, not to mention a callback from the Kansas Highway Patrol. But there were also so many hours spent perusing over 3,600 pages of trial transcripts, and talking to people with an incredible amount at stake in the project. The end result is a story that I hope y’all will read and pass along—the tale of a creative genius who became a casualty of the War on Drugs.

Special thanks go out to Paul Pope, who provided the story’s perfect illustrations. The one above (click to enlarge) is based on photographs I took in the central character’s San Fernando, Calif., garage.

Tags:Alfred Anaya·crime·War on Drugs·Wired·writing

March 19th, 2013

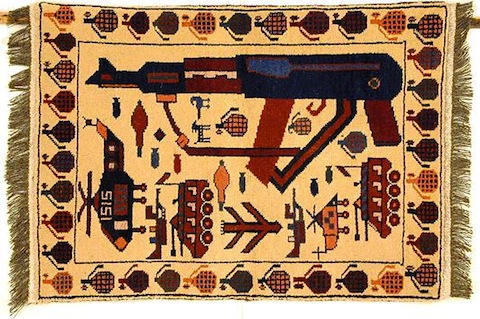

One of the tangential characters in The Skies Belong to Us is the late William L. Eageleton, one of the most storied diplomats of the Cold War. When he wasn’t busy representing American interests in global hot spots, Eagleton passed the time by delving into the minutiae of rugs: He was a noted collector of Middle Eastern and North African rugs, as well as the author of an authoritative book on the topic. Tracking his interest in the art form led me the archives of Oriental Rug Review, a wonderfully geeky journal dedicated to the world’s unheralded weavers.

One of the tangential characters in The Skies Belong to Us is the late William L. Eageleton, one of the most storied diplomats of the Cold War. When he wasn’t busy representing American interests in global hot spots, Eagleton passed the time by delving into the minutiae of rugs: He was a noted collector of Middle Eastern and North African rugs, as well as the author of an authoritative book on the topic. Tracking his interest in the art form led me the archives of Oriental Rug Review, a wonderfully geeky journal dedicated to the world’s unheralded weavers.

Much of the journal’s content is only available on paper, but a few in-depth articles have been posted on The Tubes. One of my favorites is this lengthy examination of Afghan war rugs, which includes some incredible photos of rugs created in the aftermath of the Soviet invasion. A highly recommended read for anyone who shares our fascination with the way in which conflict shapes creativity.

Tags:Afghanistan·art·rugs·William Eagleton

March 15th, 2013

Having been raised to think that all of the Soviet Bloc resembled the drab realm depicted in this infamous Wendy’s ad, I’m always amused to come across depictions of our Cold War foes basking in the sun. The photo above, of a crowded beach in Odessa, is part of a terrific Ian Berry series from 1982, which includes several more shots of Ukrainians of varying shapes and sizes stretched out on the sand—along with more stereotypical depictions of the city’s bleak corners. Check out a great sampling from the collection here, via the always stellar Vintage Everyday.

Having been raised to think that all of the Soviet Bloc resembled the drab realm depicted in this infamous Wendy’s ad, I’m always amused to come across depictions of our Cold War foes basking in the sun. The photo above, of a crowded beach in Odessa, is part of a terrific Ian Berry series from 1982, which includes several more shots of Ukrainians of varying shapes and sizes stretched out on the sand—along with more stereotypical depictions of the city’s bleak corners. Check out a great sampling from the collection here, via the always stellar Vintage Everyday.

Tags:Communism·Ian Berry·photography·Soviet Union·Ukraine

March 13th, 2013

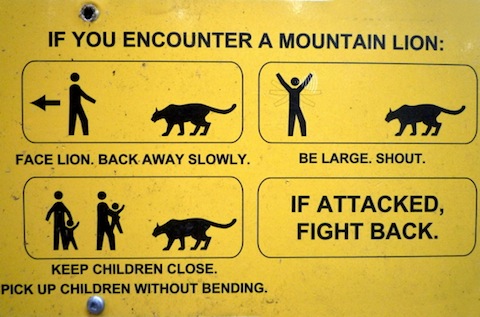

Here at Microkhan world headquarters, there are few things we admire more than passionate attention to detail, especially when it’s in the service of chronicling the arcane. And so you can imagine our joy upon encountering this awesomely comprehensive list of bygone mountain lion attacks, which does an excellent job of illustrating North America’s century-long transformation from rugged expanse to giant exurb. The list also contains an intriguing pivot about halfway through, one that goes to show how pop culture can subtly influence all aspects of public discourse:

Here at Microkhan world headquarters, there are few things we admire more than passionate attention to detail, especially when it’s in the service of chronicling the arcane. And so you can imagine our joy upon encountering this awesomely comprehensive list of bygone mountain lion attacks, which does an excellent job of illustrating North America’s century-long transformation from rugged expanse to giant exurb. The list also contains an intriguing pivot about halfway through, one that goes to show how pop culture can subtly influence all aspects of public discourse:

News coverage of Peter Taylor’s death in 1949 demonstrates that this may be the era when people first began to adopt our modern attitudes toward impressive, cute, and/or amusing animals, including predators. Regarding the savage killing of Peter Taylor, a newspaper opined that the cougar was merely “defending what was his own.” This is the first evidence I have found of this now common attitude beginning to emerge. Perhaps laying the groundwork in our psyches from childhood to adulthood, Walt Disney’s influential Bambi in this same era (1942) pioneered and dramatized the concept of man as the most sinister and heartless threat to all wildlife. A few years later Disney’s “true life,” anthropomorphic, animal adventures series began portraying animals with human-like personalities.

Our threat did not diminish as a result of this newfound sympathy, of course—it just became more insidious, as habitat destruction in the name of development replaced outright hunting as the mountain lion’s great affliction. You can see why the great cats might want to seek their revenge on the occasional wayward hiker.

(Image via Hilobrow)

Tags:animal attacks·animals·environment·mountain lions

March 11th, 2013

Let me assure you that the recent slowdown in Microkhan posting is not due to my having surrendered to indolence. I have instead been busy prepping the launch of a major project in support of The Skies Belong to Us: Skyjacker of the Day.

Let me assure you that the recent slowdown in Microkhan posting is not due to my having surrendered to indolence. I have instead been busy prepping the launch of a major project in support of The Skies Belong to Us: Skyjacker of the Day.

Over the next hundred days, I’ll be profiling a hundred skyjackers from the Sixties and Seventies—mostly Americans, though I reserve the right to toss in the occasional Japanese militant or Cypriot nationalist. The series launches today with a sketch on Frederick Hahneman, best known for parachuting into the Honduran jungle while clutching $303,000 in ransom.

Be sure to check back daily for updates, and please pay a visit to the new The Skies Belong to Us website when you can. Feedback regarding bugs and errors appreciated, and potentially rewarded with some book-related trading cards down the line.

Tags:aviation·hijacking·Skyjacker of the Day·The Skies Belong to Us

March 8th, 2013

The annual Musikahan sa Tagum, which just wrapped up its 2013 edition, touts itself as the premier music festival in the entire Philippines. I don’t know enough about that nation’s arts scene to judge the validity of that claim, but I certainly can’t stop watching videos of the Musikahan’s marching-band competition. (The one above, for example, features an epic transition between “Fame” and “Don’t Stop Believin'” about midway through.) The event seems a perfect example of our species’ wondrous knack for hacking culture—the musicians here have taken a distinctly American art form and made it all the more splendid. What I love most about these performances is the way they don’t seem weighted down by their influences—they are not just imitating the stuff of SEC halftime shows, but rather spinning out their own thoroughly Filipino spectacle.

Oh, and be sure to watch for the dancers who kick in around the 3:30 mark. Love how they seem to be doing their own thing to some extent—minor rebels amidst the straitjacketed order of the march.

Tags:marching bands·music·Musikahan sa Tagum·Philippines·sociology

March 6th, 2013

I was recently intrigued to learn that 45 percent of the world’s opiate alkaloids—that is, the ones incorporated into prescription medicines rather than illicit narcotics—come from Tasmanian poppies. The Australian state’s dominance in this industry is the result of several factors, starting with its unique geography; tucked away in the Southern Hemisphere and surrounded by water, it has natural security advantages over more accessible rivals. But Tasmanian poppy growers have also benefitted from astute regulatory oversight, which has included healthy public investment in agricultural research—research that has dramatically increased the per-poppy opiate yield over the decades.

I was recently intrigued to learn that 45 percent of the world’s opiate alkaloids—that is, the ones incorporated into prescription medicines rather than illicit narcotics—come from Tasmanian poppies. The Australian state’s dominance in this industry is the result of several factors, starting with its unique geography; tucked away in the Southern Hemisphere and surrounded by water, it has natural security advantages over more accessible rivals. But Tasmanian poppy growers have also benefitted from astute regulatory oversight, which has included healthy public investment in agricultural research—research that has dramatically increased the per-poppy opiate yield over the decades.

But Tasmania evidently isn’t producing enough poppies, at least according to TPI Enterprises, the dominant processor on the island. TPI now wants to import additional poppies from Turkey, a plan that is causing no small amount of consternation among their domestic growers. To press their case, those growers are arguing that TPI’s Turkish plans could undermine Tasmania in some rather unexpected ways:

At the hearing, held in Launceston, Tasmanian Farmers and Graziers Association’s Jan Davis raised concerns surrounding biosecurity, which Mr Rice shared.

“If you’re going to import 2000 tonnes of raw poppy capsule into Tasmania and that’s going to take a minimum of 150 to 200 containers … the bio-sec and risk associated with that is enormous,” he said.

Mr Rice said there was also the issue of intellectual property theft, with Tasmanian poppy seeds being taken over to Turkey to be modelled and grown.

I find the last point most interesting, and perhaps most convincing. While it is hard to imagine a transnational crime syndicate having the wherewithal to steal massive quantities of poppy capsules from container ships, I can easily see the dangers in poppy-related IP theft. Yield is everything in industries such as this, and the secrets of those yields are bound up in the unique genetic makeup of each seed. If a country with lower labor and land costs can figure out how to produce a crop on par with Tasmania’s, they could dominate the market a decade down the line. The advantages of being a remote island can only take Tasmania so far.

Tags:agriculture·drugs·opium·poppies·Tasmania·trade·Turkey

March 5th, 2013

Apologies for the late jump on the week, but I’m swamped with prepping an excerpt from The Skies Belong to Us. Back tomorrow with thoughts on the brouhaha in Tasmania’s poppy industry; in the meantime, take a moment to learn about the hardships of driving a taxi in Port Moresby.

Tags:Papua New Guinea·Port Moresby·transportation

March 1st, 2013

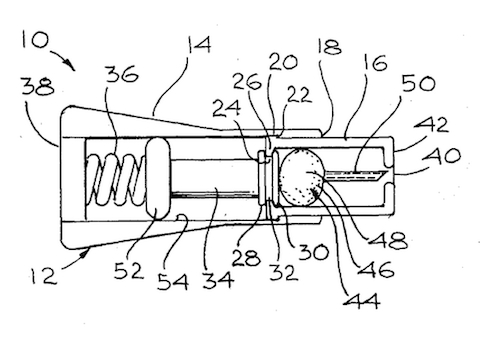

In an attempt to flesh out the nascent The Skies Belong to Us mood board, I have been combing through reams of patents for anti-hijacking devices. Most are deliciously zany, such as this capture chamber or this trick chair. The hijacking epidemic of the late 1960s and early 1970s certainly seems to have fired up the imaginations of inventors who spent their formative years watching secret-agent flicks at the local movie palace.

In an attempt to flesh out the nascent The Skies Belong to Us mood board, I have been combing through reams of patents for anti-hijacking devices. Most are deliciously zany, such as this capture chamber or this trick chair. The hijacking epidemic of the late 1960s and early 1970s certainly seems to have fired up the imaginations of inventors who spent their formative years watching secret-agent flicks at the local movie palace.

Reading slightly off-center patents is a true pleasure for those who enjoy tangents, for each document offers handy links to related inventions. By perusing the citations for the trick chair, for example, I was led to this bonkers gadget, which presents a classic case of best intentions gone awry. The first paragraph of the abstract speaks for itself (with apologies for the anatomically frank language):

An anti-rape device having a hollow housing adapted to be worn within the human vagina. The housing has a front opening and contains a hypodermic syringe having a volume of rape-deterring fluid and a needle facing and aligned with the front opening. Actuator means in the housing are provided which include housing means such as a spring to force the needle through the front opening and inject the fluid, cocking means to cock the device into a position which totally shields the needle within the housing, and prevents action of the spring, and trigger means which automatically releases the cocking means, upon forceful penis penetration of a vagina containing the device, to permit the spring to protrude the needle and inject the fluid into the penis. Preferably, the fluid is a quick-acting, safe narctoc such as scopolamine, or the like to render the rapist unconscious.

More detailed (and, I assure you, completely safe-for-work) drawings here. I could unearth no evidence that this device ever went into production, perhaps because early market research revealed that the target consumers might be a wee bit skittish about carrying around scopolamine-filled needles inside their bodies.

Tags:gadgets·patents·public safety·technology

February 28th, 2013

I have been reluctant to comment on the recent witch burning horror in Papua New Guinea, even though I have previously written at length about that nation’s problems with stamping out superstition-related violence. There was something alarmingly voyeuristic about the way in which the murder was covered, and I didn’t think it appropriate to chime in when others were busy leering at the terrible events in question. But enough time has now passed for more sober takes to pop up, and one of the best comes through the eyes of a Catholic priest who has spent four decades in Papua New Guinea. He coolly explains why the belief in sorcery persists in rural areas of his adopted country, and one of the reasons he offers has to do with the nation’s lack of bureaucracy:

I have been reluctant to comment on the recent witch burning horror in Papua New Guinea, even though I have previously written at length about that nation’s problems with stamping out superstition-related violence. There was something alarmingly voyeuristic about the way in which the murder was covered, and I didn’t think it appropriate to chime in when others were busy leering at the terrible events in question. But enough time has now passed for more sober takes to pop up, and one of the best comes through the eyes of a Catholic priest who has spent four decades in Papua New Guinea. He coolly explains why the belief in sorcery persists in rural areas of his adopted country, and one of the reasons he offers has to do with the nation’s lack of bureaucracy:

Gibbs said he tried to convince his parishioners to take a more modern and scientific view of the world “such as asking a medical doctor the cause of death,” saying medical authorities need to be more open about causes of death, and in a country that often has no death certificate system, he wants one. Oddly, people will accept a death by heart attack; but not high blood pressure.

A great number of attacks on “witches” come after someone—usually a child—has suddenly fallen ill and died. Absent of any formal explanation of how such a tragedy could have occurred, the superstitious seek scapegoats. A great many innocent lives could be saved if the government could somehow help grieving relatives understand that their loved ones were victims of terrible luck, rather than dark arts. Something as simple as a piece of paper with an official stamp certainly might help bolster the legitimacy of such an official explanation.

Tags:bureaucracy·medicine·Papua New Guinea·sorcery

February 26th, 2013

Double Wired deadline today, plus tweaking a soon-to-launch Web project related to The Skies Belong to Us. Back tomorrow with something slightly more erudite than footage of Loni Anderson strutting across a field of broken glass.

Tags:Circus of the Stars·circuses·daredevils·Loni Anderson·TV

February 25th, 2013

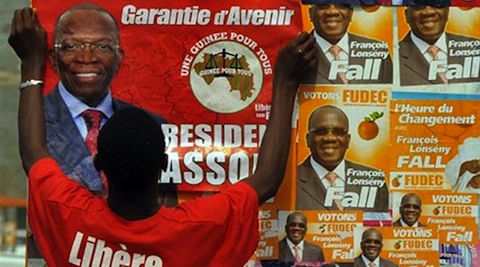

Guinea’s political opposition is none-too-pleased with the current regime’s decision to outsource the management of May’s election to Waymark, a South African information technology firm. At first glance, these objections may seem flimsy, based more on xenophobia than legitimate fear of cronyism. But if you scratch beneath the surface a bit, you can get a sense of the very specific reasons why Guinean opposition leaders are skeptical of Waymark’s credentials:

Guinea’s political opposition is none-too-pleased with the current regime’s decision to outsource the management of May’s election to Waymark, a South African information technology firm. At first glance, these objections may seem flimsy, based more on xenophobia than legitimate fear of cronyism. But if you scratch beneath the surface a bit, you can get a sense of the very specific reasons why Guinean opposition leaders are skeptical of Waymark’s credentials:

Benin alleged in 2008 that the [Waymark] system it used was unreliable and the manner in which it secured the contract was questionable. [Waymark] was chucked out early in tendering for the Cameroonian election this year. In South Africa, Waymark was axed by the Department of Trade and Industry after it was accused of improperly securing an R11m contract to maintain information technology for the former Cipro (now the Companies and Intellectual Property Commission).

It was alleged that President Condé’s son, Mohamed Alpha Condé, worked for Waymark at one stage and introduced the company to the administration…It was reported that the Guinean finance department said Waymark’s contract work amounted to $3m, but the invoice was for $14m. And the United Nations website reveals that Waymark was removed from its list of approved service providers in September 2008.

There isn’t much hard evidence to back up some of the more explosive allegations against Waymark, but there is one notable negative about the company that anyone can check out for themselves: its laughably lackluster website. Tough to imagine trusting a shaky democracy to a company that can’t get basic HTML right.

Tags:corruption·elections·Guinea·politics·software·South Africa·technology·Waymark

February 21st, 2013

Approximately two years ago, the Fiji Times reprinted a story from New Zealand’s Sunday Star Times in which a soccer official questioned the ethical soundness of Fiji’s judiciary. The military dictator who runs Fiji as his personal fiefdom did not take kindly to such an insinuation, even though even a casual observer of the island nation can recognize the criticism as true. And so the Fiji Times now finds itself in a sticky legal situation, having been found guilty of contempt of court and fined the equivalent of $170,000. The newspaper was compelled to cover its own punishment, which it did so in the gentlest terms possible:

In 2011, Tai Nicholas made comments to a reporter of the New Zealand-based Sunday Star Times responding to questions on former Fiji Football Association president Dr Muhammed Shamsud-Dean Sahu Khan’s official position in the OFC and FIFA (International Federation of Football Association).

The Sunday Star Times article that contained Mr Nicholas’s comments was published verbatim in this newspaper the following day.

Those comments, according to an affidavit filed by the Attorney-General’s office in November 2011, were said to “scandalise the court and the judiciary of Fiji in that they were a scurrilous attack on the members of the judiciary, thereby lowering the authority of the judiciary and the court”.

In his judgment, Justice Calanchini said this was a case of contempt of court which should be punished by a penalty that reflects the public interest, acts as a deterrent and appropriately denounces the conduct of the respondents.

Whether the tiny Fiji Times can continue to operate with such a judgment hanging over its head is anyone’s guess. I am certain that the powers-that-be in Fiji would prefer that it shut down. Those at the helm of the newspaper must decide not only whether they can survive financially, but whether they wish to risk further harassment. The fact that they are faced with such a difficult choice bodes incredibly ill for Fiji’s future.

Tags:censorship·dictatorship·Fiji·Fiji Times·Frank Bainimarama·journalism·New Zealand·newspapers

February 19th, 2013

The adulation accorded Lawrence Wright’s Going Clear motivated me to look up the very first Scientology exposé I can remember: Richard Behar’s 1991 Time investigation, which irked the Church to no end. That piece made me a lifelong fan of Behar, whose meticulous approach to reporting is something I’ve sought to emulate in my own career.

The adulation accorded Lawrence Wright’s Going Clear motivated me to look up the very first Scientology exposé I can remember: Richard Behar’s 1991 Time investigation, which irked the Church to no end. That piece made me a lifelong fan of Behar, whose meticulous approach to reporting is something I’ve sought to emulate in my own career.

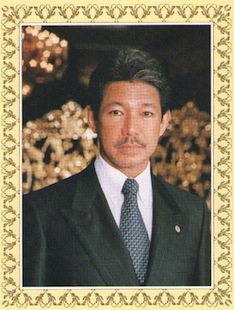

My favorite Behar piece is his 1999 Fortune account of shenanigans in Brunei’s royal family. Astoundingly, Behar managed to snag an interview with the notoriously profligate Prince Jefri, a man who otherwise shuns the media. That interview reveals a man who, by virtue of his spectacular wealth, has no need to engage with everyday reality:

The prince–flanked by a $160,000 pair of solid-gold tissue dispensers–spoke less in sentences than in syllables. He giggled and glared and cocked his head as if I’d just fallen through the roof in a full suit of armor.

“Jefri is not geared for questions,” explained an apologetic aide. “He is painfully shy,” added another. Jefri did manage to say that he was “looking forward” to his return to Brunei, that he missed the Sultan, and that he was “upset, confused, disappointed” when his assets were suddenly seized. I asked how long he planned to stay in Brunei. “I’m very open,” he responded. I tried another tack. Will the Sultan see you? “He knows I’m coming.” Laughter filled the room, but I’d somehow missed the joke. Have the two of you spoken by phone? “Yes, it is good that way. He asked me about the weather in New York.”

I wanted Jefri’s views on the events swirling around Brunei. “You ask me? You were there.” Again, more laughter. When I asked about Aziz and the conservatives, Jefri said that “they would have their own agendas.” And what are those agendas? “You can tell me,” the prince responded. Chuckles all around.

Clearly, this was the stuff of history, so I pressed on. I told Jefri it seemed that certain government officials wanted his country to become more conservative. “They didn’t tell me,” he responded. I also told him it was obvious from my visit to Brunei that he had done many things to open up the society. “What did I do?” he asked, sounding alarmed and confused.

Jefri never says anything of consequence in the interview, but his inability to observe basic norms of human communication speaks volumes about his character. This is a man for whom fellow members of his species are mere abstractions.

Tags:Brunei·journalism·Prince Jefri·reporting·Richard Behar

Less than 48 hours to go ’til The Skies Belong to Us officially drops, which is why I’m spending Father’s Day locked in the yurt, endeavoring to spread the good word. You can aid the cause by checking out this enthusiastic review from The New York Times, in which the book is described as “such pure pop storytelling that reading it is like hearing the best song of summer squirt out of the radio.”

Less than 48 hours to go ’til The Skies Belong to Us officially drops, which is why I’m spending Father’s Day locked in the yurt, endeavoring to spread the good word. You can aid the cause by checking out this enthusiastic review from The New York Times, in which the book is described as “such pure pop storytelling that reading it is like hearing the best song of summer squirt out of the radio.”

There’s no question that the animal-rights movement has successfully altered America’s attitude toward fur; coats composed of pelts are no longer a de rigueur status symbol for those with too much money on their hands. So why, then, is mink production ramping up to virtually unprecedented levels? Because the newly affluent Chinese

There’s no question that the animal-rights movement has successfully altered America’s attitude toward fur; coats composed of pelts are no longer a de rigueur status symbol for those with too much money on their hands. So why, then, is mink production ramping up to virtually unprecedented levels? Because the newly affluent Chinese

I was recently intrigued to learn that 45 percent of the world’s opiate alkaloids—that is, the ones incorporated into prescription medicines rather than illicit narcotics—come from Tasmanian poppies. The Australian state’s dominance in this industry is the result of several factors, starting with its unique geography; tucked away in the Southern Hemisphere and surrounded by water, it has natural security advantages over more accessible rivals. But Tasmanian poppy growers have also benefitted from

I was recently intrigued to learn that 45 percent of the world’s opiate alkaloids—that is, the ones incorporated into prescription medicines rather than illicit narcotics—come from Tasmanian poppies. The Australian state’s dominance in this industry is the result of several factors, starting with its unique geography; tucked away in the Southern Hemisphere and surrounded by water, it has natural security advantages over more accessible rivals. But Tasmanian poppy growers have also benefitted from

Guinea’s political opposition is

Guinea’s political opposition is