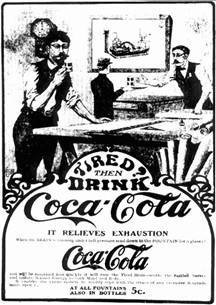

Back during our days writing Slate‘s “Explainer” column, we were once asked to tackle a statistically tricky question: Could self-styled moral watchdog William Bennett really have, as he claimed, broken even playing high-stakes slot machines for over a decade? (Quickie answer: Almost certainly not, unless the man is blessed with Ashley Albright levels of luck.) Doing the research on that piece led to an ongoing fascination with the psychology of slot machine players, a topic of much discussion amongst gambling researchers. What is it about those blinking lights, spinning wheels, and teaser payouts that keeps folks rooted on their stools for hours on end? And why does this activity lead to an addiction for some, while others (present company included) can’t stand the thought of spending more than five minutes pulling a one-armed bandits lever?

As it turns out, researchers have been hard-pressed to answer these questions. The reasons for that frustration are compiled in this paper, which also suggests some ways for researchers to obtain better results. Among the suggestions? Get an undercover job:

One way to collect invaluable data is to work in a gaming venue, an approach that has been taken by prominent researchers in this field. For example, Sue Fisher collected all of her observational data while employed behind the change counter of her local amusement arcade. Employment within the environment can be used to establish the researcher’s identity and allow blending into the environment. Slot machine gamblers are usually unaffected by onlooking staff because there is no real risk of staff playing their machine when they have finished their gaming (see “skimming” referred to above). Hence, staff are fully permitted to observe playing behaviour and are often required to do so to be vigilant for fraudulent practices. Furthermore, while submerged in this social world, researchers can gather large amounts of relevant and fruitful information indirectly through participation in the gambling environment. We recently utilised this approach to obtain data and it proved effective.

Clever, but ethical? And might a casino have cause to sue a researcher who used their job to gather scientific data? We wonder if the Food Lion precedent might apply here, though that obviously dealt with journalists rather than academic researchers.

(Image via Casino Snob)

Growing up in Los Angeles, we were annually subjected to a series of PSAs cautioning against

Growing up in Los Angeles, we were annually subjected to a series of PSAs cautioning against

Sad news out of Moscow, as word comes that Vladimir “Dynamite” Turchinsky has

Sad news out of Moscow, as word comes that Vladimir “Dynamite” Turchinsky has