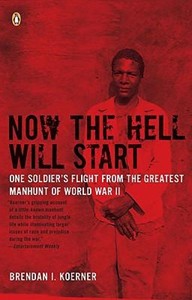

The Bengal Famine of 1943 receives barely two paragprahs’ worth of ink in Now the Hell Will Start, a lamentable oversight that we now hope to correct as part of NtHWS Extras Month.

The Bengal Famine of 1943 receives barely two paragprahs’ worth of ink in Now the Hell Will Start, a lamentable oversight that we now hope to correct as part of NtHWS Extras Month.

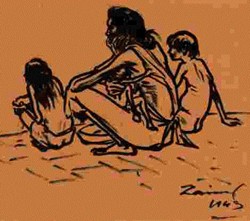

Our interest in the famine has less to do with its devastating scale—as many as 4 million Indians may have perished from hunger—than its obvious preventability. Because so much of Eastern India’s arable land was given over to tea production, the British raj made Burma the region’s bread basket—or, more accurately, its rice basket. When the Japanese conquered Burma in 1942, however, the British made no discernible effort to find an alternate source of food for Bengal. Within a year, entire families were literally wasting away in the streets of Calcutta. The New Republic neatly summarized the horror:

The national, provincial and municipal governments of India, Bengal and Calcutta vied with each other in complacency, procrastination and inefficiency. Bureaucrats got snarled in red tape; food merchants profiteered shamelessly (even now the price of rice, the staple diet of the province, is up 500 percent). Although anyone should have seen catastropher approaching, the government of India waited a whole year after the Japanese took Burma, the main source of rice for Bengal, before it worried about food. Then it set up a bureau which did little except to issue pamphlets which, in the style of Eric Johnston, glorified “free enterprise.” The government says about a million died; [The New Statesman] thinks the total will be closer to three millions (sic), as cholera, malaria and smallpox follow in the wake of starvation. Whole areas are almost depopulated; sometimes the survivors are too weak to bury the dead, and leave them to the competition of dogs and vultures.

What Microkhan would give to find one of those pamphlets designed to assuage the masses that their empty bellies were simply a product of the market struggling toward maximum efficiency.

Some chilling contemporary photos of the famine here. And a Bengali short-story about the tragedy, translated by Kalpana Bardhan, can be read here.