December 4th, 2012

As we recently explored in our post about wildlife strikes, even the most advanced technology cannot withstand Mother Nature’s meddling. Roller coasters are another case in point, as explained in this rather fascinating bit by a veteran amusement-park techie:

A ride error is usually caused by an issue with the photo eye sensors…On Talon, the train has eight cars, so the photo eye needs to have its connection broken eight times so that the computer knows that all eight cars have traveled through the course. There are several photo eye sensors on the ride, including a set at each end of the station, a set on the lift, a set near the trim brake at the bottom of the Immelman loop, and then multiple sets on the brake run.

When a sensor is not broken eight times exactly, the computer senses that something is wrong. In the most drastic case, a car has become detached from the rest of the train. In this case, the sensor may only be broken seven times, so the sensor immediately relays the information to the computer that something is wrong and the ride must emergency stop, which is why sometime rides will stop on the brake runs, lift hills, or even halfway in or out of the station, because power is immediately cut off from the ride and all of the brakes close to avoid collisions.

This is a great insight as to how safe rides truly are, but that doesn’t explain why a ride error may occur when everything is running fine. In most cases, it is simply a bird, bug, or butterfly landing on the photo eye, causing it to be broken but not the correct number of times. The computer thinks something is wrong and shuts down the ride.

In other words, an insect the size of a thumbnail can cause a $13 million piece of hardware to screech to a halt. The more elaborate our systems, the greater their vulnerabilities to the tiniest of actors.

(Image via What’s His Face)

Tags:amusement parks·insects·roller coasters·technology

November 30th, 2012

Since I’m in the habit of noting significant Microkhan miletones, I feel obligated to alert y’all to the fact this is my fifteen-hundredth post. Thanks a million to everyone who has followed this often ragtag project since its launch nearly five years ago; I promise that good things lie ahead, especially once I get the next book off my plate. Though I’ve been tempted to abandon Microkhan on several—okay, numerous—occasions, I know I’d miss having this public scratch paper. And I’d definitely miss engaging with the learned commentariat about topics ranging from linguistics to lifeboats. Please do keep swinging by, and prepare for an awesome deluge of hijacking-related posts as the launch date for The Skies Belong to Us draws near.

Tags:housekeeping·The Skies Belong to Us

November 29th, 2012

We last wrote about Tonga’s unusual space enterprise, Tongasat, back in December 2010, when we focused on the alleged religious motivations of Princess Pilolevu Tuita, the firm’s majority shareholder. After a long quiet spell, the controversial company is now back in the news, as a pawn in a political tug-of-war between a Tongan opposition leader and the nation’s current prime minister. The issue is a rather substantial windfall that Tongasat recently enjoyed, courtesy of the government of China. The story gets broken down here:

Claims in Tonga’s parliament that there was an illegal transference of government money to Tongasat have been denied by two Prime Ministers, in a row over how a USD$75 million grant from China to Tonga was used.

A payment of USD$25.45 million that was given by government to Tongasat in 2011 was approved by the former Prime Minister Lord Dr Feleti Sevele and came from a grant given by the Chinese government to Tonga in 2008…

Lord Sevele told Matangi Tonga last week that the $75.35 million Chinese grant to the Tongan government in 2008 was “not like other Chinese grants”, and there were reasons for that, which he asserted that he did not want to get into.

“If there was no Tongasat there would not have been any such grants. The grant were made because Tongasat was leasing orbital slots to the Chinese.”

But as to why the Chinese Government did not pay their dues straight to Tongasat, instead of giving the Tongan government a grant, then for the government to pay Tongasat, was not made clear.

Check out this excellent piece from The Space Review for more background on Tongasat’s sleight-of-hand. It’s clear to me that the Tongan royal family is earning a fortune by capitalizing on a public asset—namely, the orbital slots that the country is entitled to by international law. Call us cynical, but the “grant” just seems like a fig leaf designed to make this seem like a government-to-government transaction, rather than a pure pay-off to a privately held enterprise. Par for the course in Tonga, alas.

Tags:China·corruption·space·Tonga·Tongasat

November 28th, 2012

Wobbling beneath the weight of two major projects at the moment—my next Wired opus and the copy edit for The Skies Belong to Us. In my brief absence, please marvel the awesomely sophisticated space monsters from 1962’s Planeta Bur, a masterpiece of Soviet sci-fi schlock.

Tags:movies·Planeta Bur·Soviet Union

November 26th, 2012

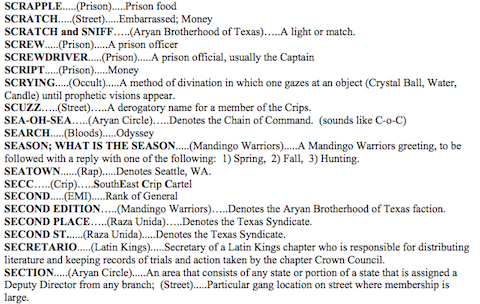

There are two things to marvel at in the Texas Prison Gangs Dictionary, which comes to us via the good folks over at Public Intelligence. The first is the incredible effort it took to document 168-pages worth of vocabulary that is expressly designed to be as indecipherable as possible. The second is the sheer linguistic inventiveness of the incarcerated, who essentially commit themselves to learning a second tongue in order to thrive behind bars. I would love to read a learned linguist’s take on whether all languages originate in not-too-dissimilar manners—as efforts to conceal the machinations of one group from those in power. Based on what I know about how English grew out of a vernacular employed by peasants whose masters spoke courtly French, I bet there’s more than a grain of truth to that assumption.

Tags:crime·gangs·language·prisons·Texas

November 21st, 2012

I send you off into the Thanksgiving break with a special treat: an entire site dedicated to the 1981 spaceflight of Jügderdemidiin Gürragchaa, the only Mongolian to have soared into the heavens (albeit with Soviet help). The mission made Gürragchaa a national hero, a status that he later parlayed into a political career.

What is most incredible about the site is its logorrheic attempt to explain the scientific import of the mission. We remain convinced that the mission was primarily intended as a morale booster for Mongolia, which certainly needed good reason to stay in the diminishing Soviet fold. But we must confess that we’re intrigued by the experiment on display here; the photo’s caption on the site reads:

The projects “Chatsrgana/Buckthorn/” and “Borts/Dry meat/” prepared by Mongolian scientists is being introduced (Lkhagva and Urtnasan)

Perhaps that important advances in celestial borts knowledge justifies the triumphalism on display here.

Tags:Jügderdemidiin Gürragchaa·Mongolia·Soviet Union·space

November 19th, 2012

Aside from being the native land of Microkhan’s most beloved soccer star, Benin is also currently home to one of the sketchiest political dramas in the Eastern Hemisphere. To hear the nation’s government tell it, President Yayi Boni (above) narrowly escaped death when a plot to poison him fell apart—a plot masterminded by a wealthy businessman named Patrice Talon, one of Boni’s staunchest former allies. But the details of the case seem more than a little head-scratching, to the point that the plot’s existence must be called into question. Talon himself recently weighed in from exile, and his interview with Radio France Internationale (translated from French) provides a compelling peek inside the machinery of a corrupt, dysfunctional state. Suffice to say that Talon admits nothing, and blames the whole affair on a falling out between himself and his powerful ex-friend:

Q: After the victory of Boni Yayi, you secured big markets, such as the management of the PVI, the audit programme of imports at the port of Cotonou. A few months ago, you lost this market, why?

Talon: For me, it may be a punishment.

Q: Is it for the same reason that you lost the monopoly on imports of inputs, fertilizers, insecticides, in the cotton sector?

Talon: I can say that yes. Always as punishment, it was brutally decided that the intervention of the private sector must stop; a sector, which is a responsibility for private activities in Benin for almost two decades. Therefore, everything was stopped overnight. But this is not the first time. I was stopped like that in the past, arbitrarily, for two years. I waited. You know, when you know you are right, you wait for the return of the truth. I`m used to it. One must also agree to get accustomed to this kind of setback and be patient. I know how to do this.

Q: This is the story of Superintendent Fouquet under Louis XIV! You became too rich, too powerful?

Talon: It is to be believed, but I think that my misfortune is to be too independent at times, not putting my person totally at the service of things which I do not believe in.

Talon is so obviously arrogant that it’s tough to entirely trust his denial of involvement in the alleged poisoning plot. But what he says about the unpredictability of Boni does ring true; the powerful have a way of turning on their closest associates for reasons that are clear to no one but themselves.

Tags:assassination·Benin·corruption·Patrice Talo·politics·Yayi Boni

November 16th, 2012

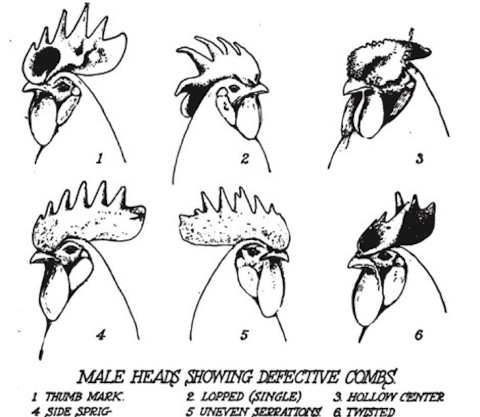

Parent-teacher conference plus Wired deadline make today too hairy to Microkhan. See you back here on Monday, by which time I expect each and every one of you to have completed all 341 pages of The Mating and Breeding of Poultry. There will be a quiz.

Tags:poultry

November 14th, 2012

I first became aware of Tajikistan’s tiny rock scene this past summer, when I read this dispatch about the straight-edge, black-metal band Al-Azif. I am always drawn to stories about artists who create despite hardship, and so I was naturally intrigued by the band’s zeal for playing Western music in such an oppressively conservative country. This more recent piece explores the scene further, and makes the case that one of the most irritating rap-rock acts in history may actually have a redeeming quality:

One Dushanbe band, Red Planet, is perhaps even more unorthodox than Al Azif. Taking to the stage in a rhinestone-encrusted T-shirt, 19-year-old Umida Fazilova gives a nod to her identical twin sister, Khursheda, sitting behind the drums and launches into a set of high-energy and emotionally charged metal.

“When I started playing rock music, everyone was laughing at me during our concerts,” Khursheda Fazilova said. “They think drums are not for women.”

The members of Red Planet met at a university and bonded over their love of Western heavy-metal bands such as Linkin Park. Although the Western influences in the Tajik rock scene are strong, the local style has an Eastern slant all of its own.

“Sure, we’re influenced by Western hard rock, punk, hard-core and even pop, but our roots are from the East,” Mr. Rock said. “We have songs with specific beats with Oriental melodies.”

Not quite sure I can detect the “Oriental melodies” in the Red Planet clip above, but I can’t help but love them nonetheless. There are few things more beautiful than people creating offbeat art against all odds. And Umida Fazilova has a fantastic coat.

Tags:Al-Azif·Dushanbe·heavy metal·music·Red Planet·Tajikistan

November 13th, 2012

The object above washed ashore in the Hawaiian district of Ka’u last month, and has remained immobile ever since—no great surprise, perhaps, given that it weighs an estimated seven tons. State authorities are now in the process of two vital tasks: Figuring out how to dispose of the monstrosity, and figuring out what the heck it might be. The former mission will involve chopping up the object into bite-sized chunks that can then be airlifted away by helicopters; the latter will require the wisdom of someone well-versed in the taxonomy of gargantuan yellow things.

Are you that person? Care to hazard a guess as to what the object might be? I am leaning toward the Monolith hypothesis, which would indicate that alien super-beings are actually much less elegant craftsman than Arthur C. Clarke had envisioned.

Tags:Arthur C. Clarke·debris·Hawaii·Monoliths·sci-fi

November 9th, 2012

Okada are Lagos motorcyclists who earn cash by zipping customers through traffic, often with little regard for safety. The regional government recently banned okada from all major roadways, in part because the bikes are often used by robbers to flee from crime scenes. The prohibition hasn’t gone over well, however, for okada are more than just automotive hustlers—they’re also part of a distinct subculture that centers around a shared love of speed. And they are lashing out at the policemen enforcing the ban, who have no qualms about using violence at will.

If I were a betting man, I would ultimately place my money on the okada. They provide too valuable of a service to the general public—a last resort for people who are late for important appointments, and have no choice but to risk their lives to reach their destinations in time. Until Lagos is cured of its endemic traffic problems, there will always be plenty of demand for the okada. And it is ultimately demand that settles disputes like this, not policies issued from on high.

Tags:Lagos·Nigeria·okada·traffic

November 8th, 2012

As I learned so long ago in the mind-blowing Summer of My German Soldier, thousands of Axis prisoners-or-war were housed in Arkansas during World War II. Upon their release at conflict’s end, many of the former captives kept in touch with their American bosses—the men they were forced to pick cotton for, in exchange for meager wages. As this amazing collection of letters demonstrates, there was a certain odd affection between the ex-POWs and their Razorback taskmasters:

Destruction here in Western Germany is unimaginable. Living conditions are awfully bad. Food is very scarce. My imagination very often goes back to those lucky times when we were working for you. Of course I am glad I am a relatively free man again, but there is hardly a possibility to enjoy one’s freedom. We are all working very hard to help to overcome the terrible destruction and emptiness left by the Nazi regime; it will take years and years, however, before there will be normal conditions again. In general, the German population is very willing to try to correct its faults. There are, in this zone at least, no signs of unrest and trouble, as far as I know. Maybe some day there will be a truly democratic Germany. That is the political aim I’m working for. I am glad I had the opportunity to learn to know parts of the American Way of Life; I hope that is the aim for Germany in political respect.

The letter-writers did seem to have an ulterior motive in many instances, though: Several of the epistles includes not-so-subtle requests for cigarettes and, more important, food. Apparently there was a time when Berlin wasn’t chock full of scrumptious doner-kebab stands.

Tags:Arkansas·books·Germany·prisons·Summer of My German Soldier·World War II

November 6th, 2012

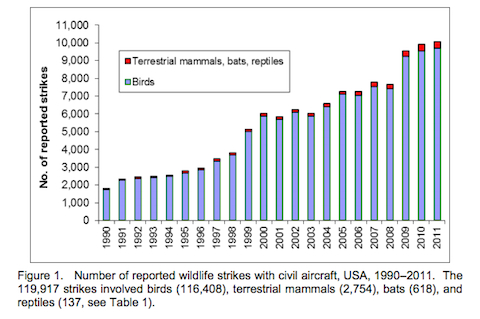

As I spend this Election Day tracking down an amazing/disturbing/tragic tale in the sunbaked flatlands of Los Angeles, I hope y’all are considering which of our aspiring rulers are most equipped to deal with our great nation’s worsening wildlife-strike problem (PDF). If you thought geese and pelicans were the main flesh-and-blood threats to America’s aircraft, the FAA would like to encourage you to think again.

Tags:aviation·FAA·wildlife strikes

November 2nd, 2012

The situation in Queens is getting a might chippy, as once again both schools and local trains are closed. The enforced isolation would be more tolerable if I wasn’t slated to skip town for a Wired assignment tomorrow. I fear greatly for the sanity of the Grand Empress, who shall be all alone here with rambunctious Microkhan Jr. and the needy Emprette. Please think good thoughts for her, and please check out the Super 8 footage above, from Dushanbe in 1982. I am fasciated by the graffiti-style mural that pops up around the 2:03 mark.

Tags:Dushanbe·Hurricane Sandy·Queens

November 1st, 2012

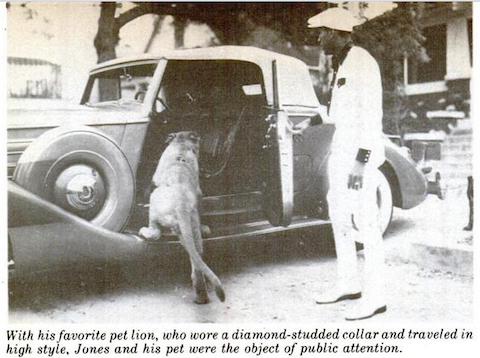

While recently listening to a few selections from Mae West’s misguided rock album, I came across the tale of one of her associates, a middleweight boxer by the name of Gorilla Jones. The exact nature of Jones’ relationship with the famously libidinous West is hard to establish—he has variously been mentioned as her bodyguard, her managee, and one of her long-term lovers. What is known for sure is that West’s money helped fund Jones favorite hobby: collecting lion cubs, which accompanied him virtually everywhere he went. The fascinating Mike Mazurki chips in his recollection of Jones’ feline predilection here:

The father of slick black flamboyancy, [Jones] entered the arena escorted by lion cubs on a leash–lions he caught in Africa with the Great White Hunter, Clyde Beatty. Flying his own airplane in 1931, Gorilla took the only dive in his career, not in the ring but into a barn in Kansas. He lost his pilot’s license, his championship belt, and his eyesight. A year later he regained both his sight and his title, but he never flew again.

A pity that a certain contemporary heavyweight didn’t credit Jones for inspiration when he went parading about with a white tiger. Stylistic flourishes can’t be copyrighted, but credit should be given where credit is due—call it the spirit of Twitter in the realm of exotic-game shownmanship.

Another stellar shot of Gorilla Jones with a feline associate after the jump. [Read more →]

Tags:boxing·Gorilla Jones·lions·Mae West

October 31st, 2012

As someone who hopes to earn a passable living through scribbled stories, I have taken an unusually keen interest in Guyana’s recent copyright brouhaha. The government of the chaotic South American nation recently had the audacity to declare that it would be purchase all its school textbooks from local pirates, who could offer far better deals than the Macmillans of the world. Guyana backed off a bit when the threat of legal action was raised, but the gambit nevertheless ended up having the desired effect, as big publishing companies were cajoled into offering steep discounts:

Cabinet Secretary, Dr. Roger Luncheon is expected to Wednesday announce that cabinet has offered its no-objection to purchase original textbooks from seven publishers for more than GUY$170 million, Education Minister Priya Manickchand told Demerara Waves Online News.

Manickchand said that while Guyana has been able to obtain a 50 percent reduction from Macmillan and 60 percent from Nelson Thorne, government would still be unable to procure all of the required textbooks. Originally, Macmillan had offered little more than 20 percent discount and Nelson Thorne 30 percent until negotiations were held with senior officials of those companies. “Now we are dealing with the big boys in these companies, they have given us massive discounts, discounts that even had my head spinning,” she said.

In other words, the publishers blinked because they understand how little leverage they ultimately hold over a vast number of nations—or, for that matter, over the international bodies that are supposed to enforce copyright norms. If Guyana had decided to opt for piracy, how much damage could the publishers really have done by pursuing legal remedies? It’s tough to deter the desperate in situations such as these.

Tags:books·copyright·Guyana·law

October 30th, 2012

Though I didn’t realize it when we moved here, the current Microkhan world headquarters occupies a relatively high-altitude slice of Queens. As a result, we suffered little meaningful damage in Hurricane Sandy—certainly nothing that a little spackle, paint, and elbow grease can’t fix. But our hearts break for fellow residents of this vast metropolis who didn’t get off so easy.

I’ll be back for sure tomorrow, once childcare has been arranged and head screwed on straight. In the meantime, enjoy Vin Scully pitching the luxury of mid-1970s air travel. I’m blown away by the fact that Continental used to have on-board pubs.

Tags:aviation·Vin Scully

October 29th, 2012

Hurricane Sandy has yet to hit Microkhan world headquarters with full force, but already there are problems—particularly in the palace’s lavatory, where a plastic skylight appears to be secured with an epoxy several notches weaker than that which magazines use to hold perfume samples in place. Working furiously to prevent a mess of rain and tree rot from entering our humble yurt; back as soon as our protection from the elements is guaranteed.

(Image via Life in Inuvik)

Tags:Hurricane Sandy·hurricanes·weather

October 26th, 2012

Out and about today, corralling some killer photos for the next book. Back on Monday with a lengthy exploration of turtle riding.

Tags:Bollywood·movies·music·Talat Mahmood

October 24th, 2012

Whoever was in charge of putting together this orientation handbook (PDF) for St. Petersburg’s migrant workers probably had the best of intentions. Yet their decision to portray those workers as mere tools, as opposed to flesh-and-blood humans like the welcoming Russians, was a revealing faux pas. As a Tajik blogger so forcefully put it:

We have been represented as tools, without souls, without bodies, and without culture. This is understandable because it is easier to offend, use, and exploit tools, without feeling a remorse.

More of the bizarrely dehumanizing (yet admittedly cute) images after the jump. [Read more →]

Tags:immigration·racism·Russia·Tajikistan

October 22nd, 2012

The fear of detection begets some of the most admirable innovation around, a technological truism proved by the photographic records of Australian Customs. These galleries are chock full of devices that smugglers have used to route around law enforcement, mostly in order to convey drugs from Southeast Asia. But there are also several wearable inventions that are specially designed to harbor illicit eggs, which are in high demand among collectors of rare avian species. The cushioned vest above, for example, was tailored to hold sixteen eggs’ worth of endangered parrots, a haul that could easily be worth in excess of $20,000.

Plenty more examples of egg-smuggling couture after the jump. [Read more →]

Tags:Australia·birds·crime·gadgets·smuggling·technology

October 18th, 2012

The typical peace of Oslo was recently shattered by one of my favorite wedding traditions: the Chechens’ enthusiasm for turning vehicular processions into demolition derbies, as participants jockey for the exalted slot just behind the bride and groom’s car. (More examples here.) Lives are occasionally lost in such a manner, which is why various governments have long tried to regulate the Chechens’ approach to celebrating their kinfolks’ nuptials. But as this account demonstrates, elites would be wise to acknowledge that they must meet the Chechens halfway:

Not long ago the President of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov, ordered shooting at weddings to be restricted: “In these cases the weapons should be confiscated, and those found responsible should be fired from their jobs, if they work in law-enforcement agencies. But if I completely forbid shooting at weddings, it would be wrong. I am not against our traditions, but it is necessary to restrict the shooting. Two or three times, not by means of heavy machine guns, are enough.

Of course, this approach can only work in a society without stringent liability laws. Because those who suffer when those bullets come down have no legal recourse in Chechnya.

Tags:cars·Chechnya·firearms·marriage·Norway

October 17th, 2012

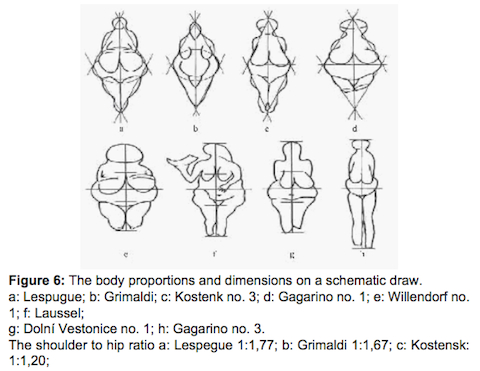

We’re all aware that standards of beauty shift over time, which is why there is such a vast difference between the body types of Peter Paul Rubens’ subjects and today’s Olive Oyl-ish fashion icons. How the taste pendulum swings seems largely tied to a basic law of economics: our species values things according to their rarity or abundance. A great example of this truism can be found in the apparent beauty ideals of our paleolithic ancestors, whose crude statues reveal that they were dazzled by curvaceous females. This recent study (PDF) of 97 female idols created tens of thousands of years ago breaks down the apparent infatuation:

Among the idols studied, 24 were skinny (mainly young ladies) and 15 normal weighed. All of these statues have small breasts, with the exception of two. More than half of the statuettes (51) are representing overweight or very obese females; their breasts mostly were also extremely large…

The association of fat to fertility has been widely discussed in anthropological literature. Through the Paleolithic Era there were frequent starvations, in fact the obesity was rare. As opposed to the sculptures where the skinny subjects are rare but the obesity is often seen. How can we solve this contradiction? I hypothetically would say, the obesity meant the ideal beauty, the prettiness, the desirable.

A slightly different take here, in which the authors contend that our statue-creating Paleolithic forebears were perhaps less interested in sex than in just surviving another godawful winter.

Tags:anthropology·art·statues

October 16th, 2012

Given that 2.4 million Americans have served in either Afghanistan or Iraq, there is bound to be a point at which some veterans who run afoul of the law will point to their combat experience as a mitigating factor. When lawyers cobble together such defenses, they will doubtless flip back to United States v. Tindall (PDF), a fascinating 1980 case in which a former Army helicopter pilot successfully argued that his combat trauma caused him to become a hashish smuggler.

The defendant, Michael Tindall, was accused of importing hashish from Morocco to Gloucester, Mass., over a six-month period. His lawyers contended that his post-traumatic stress disorder inured him to ordinary sensations, and so he was forced to try riskier and riskier endeavors just to feel some modicum of happiness:

At Tindall’s trial there was testimony that he “started to do what he called ‘crazy things.’ He would take LSD and jump into water, into the rivers and underground caves and would fly over the Everglades at a very low altitude to see if he could get what he called a rush or thrill”…The boat trip from Morocco to Gloucester represented “just another combat mission” to him.

It will be interesting to see whether contemporary juries are open to such explanations. Our collective view of the insanity defense has obviously narrowed over the past few decades.

Tags:drugs·Michael Tindall·psychology·PTSD·smuggling·Vietnam War

October 15th, 2012

So today’s the deadline for the final draft of my next book; with any luck, I’ll have some bound galleys to give away before Christmas. It’s been a long, draining process—thirty-eight months of reporting, writing, and furious pacing about my shoebox-sized home office. Tough to believe that I’m just a few hundred checked endnotes away from dropping this project into the hands of Crown’s excellent production folks.

Between now and the June 18, 2013 release date, y’all are gonna be hearing a ton about the tale. But for the moment, let me just leave you with a random paragraph plucked from what is currently page 99—a nugget that, according to Ford Madox Ford, should convince you whether or not to press forward:

He held up his Samsonite briefcase and wiggled his left index finger, the one with the metal ring around it. The crew could see that the ring was connected to a piece of cooper wire that led into the briefcase. “This controls the detonator,” he explained. “There is a concussion grenade in here, and eight slabs of C-4. Now, captain, what is your name?”

My dream is to get Morgan Freeman to do the audio book, preferably in the guise of his Electric Company DJ character (above).

Tags:books·Morgan Freeman·The Electric Company·The Skies Belong to Us·TV

October 12th, 2012

I am generally no great fan of books about mountaineering disasters, but Buried in the Sky really got its hooks into me. That’s partly because of its unique narrative viewpoint: the tale’s protagonists are not the Western adventurers who met with bitter fates on K2, but rather those adventurers’ Sherpa guides. The authors did a fantastic job not only of recounting the guides’ life stories, but also of explaining the nuances of Sherpa culture that help explain why these men were drawn to such perilous work. One such explanatory triumph is the book’s breakdown of the difference between Sherpas and Bhotes, a Nepalese ethnic group to which one of the protagonists belonged—a fact he often concealed, since it make more professional sense for mountain guides to masquerade as famed Sherpas. As it turns out, Bhotes share something rather unsavory with the more traditional residents of Kyrgyzstan:

Bhote, pronounced BOE-tay, stems from Bhot (Sanskrit for “Tibet”), and the Bhotes in Hungung observe many Tibetan customs. With marriage, for instance, the Bhotes of the Upper Arun Valley, like other Tibetan tribal groups, practice bride abduction. When Pasang’s cousin Lahmu Bhote was fourteen, the groom’s brother secured permission from her father, seized her in the night, and dragged her to the wedding. This break from her paternal household may have been ritualized, but it was hard on the bride. “I was miserable for years,” Lahmu said. It took a long time for her resentment to wear off. “When I was twenty-three,” she added, “I finally realized I loved my husband.” Sherpa marriage rites, by contrast, are public-relations campaigns. Before betrothal, a Sherpa couple consults all stakeholders—families and gods—and gets a horoscope cross-check. Sherpas widely consider the Bhote approach, which is less common nowadays, a brutal and primitive practice.

It is puzzling why two such closely related ethnic groups, which have existed in close proximity to one another for centuries, would have such wildly divergent approaches to an essential life event. Perhaps human societies do not influence one another quite as much as those who fear McDonald’s-ization have led us to believe.

Check out more about the excellent Buried in the Sky here.

Tags:anthropology·books·Buried in the Sky·marriage·mountaineering·Sherpas·Tibet

October 10th, 2012

The Micronesian Olympics—now known as the Micronesian Games for copyright reasons—were first held in 1969. As these photographs attest, the athletes competed in front of crowds that numbered in the dozens or even less. Yet those first Olympics still occupy a cherished place in the memories of Micronesian sports fans, particularly those whose tastes run toward baseball. As one of the event’s key figures recalls:

I was one of the chief organizers of the ’69 Micronesian Olympics and had the honor of watching Sotup Masatoki Steven urged on and cheer for the Chuukese team. He is truly Legendary.

Yes Susumu also is a Legend. Think he was in his early 50s when he pitched in 1969. The Palauan pitcher was Martin Ngchar. Some citizens of Micronesia call that gold medal game the greatest baseball game in the history of Micronesia.

To those lucky souls in the stands that day, that game must mean far more than the 1958 NFL Championship—even though the players involved never got their shot at the big time. Nor, for that matter, another shot at Micronesian glory; the next games weren’t held for another twenty-one year, by which time even hardy Yes Susumu couldn’t toss a slider to save his life.

Check out the full archive of 1969 Micronesian Olympics photos here. There is something quite alluring about the color processing that the developers used.

Tags:baseball·Micronesia·sports

October 9th, 2012

Mary Antisarlook, popularly known as Sinrock Mary, was at one point the wealthiest woman in Alaska. She made her fortune by controlling a herd of approximately 1,500 reindeer, which she inherited after her second husband’s death in 1900. Mary was able to keep the herd together despite numerous legal challenges to her ownership, including those filed by a Swedish schemer who alleged to be her third husband, a conniving mail carrier, and even her own nephews, who argued that Inupiat inheritance traditions always favored males. Yet Mary was also the rare tycoon who did not pay mere lip service to the notion of personal asceticism, as recounted in a definitive 1984 article from Pacific Northwest Quarterly:

The income from her reindeer permitted her to adopt 11 children and to care for countless others…Despite her wealth and success in a rather sedentary occupation that was for eign to Eskimos, who usually changed their abodes with the seasons, Mary remained in outlook an Eskimo woman who fished for salmon and tomcod, dried seal meat and fish for the winter, picked berries and greens, and prepared skins for sewing.

I am trying to picture Marissa Mayer drying seal meat, but the image just isn’t coalescing for me.

Teaser for a Sinrock Mary documentary here.

Tags:Alaska·business·reindeer·Sinrock Mary

October 5th, 2012

Back to endnoting the book today. The whole agonizing process has made me regret my lack of organization while writing—at some point, I just got tired of affixing Post-It notes to each and every primary-source document. I’m paying the price now, and I guess so are y’all—I’m too slammed to post anything richer than the street-style kuduro clip above. Back early next week with something more thoughtful, provided I can track down this one State Department report that has gone MIA in my trash-heap of an office.

Tags:Angola·dance·kuduro·music

October 4th, 2012

Please take a moment today to check out this astounding collection of mid-1970s photos from Ujelang Atoll, a Micronesian speck that once played host to nuclear refugees from nearby Enewetak. When these particular photos were taken, the Enewetakese had been in exile for three decades, after being bounced from their homes so the United States could detonate 43 nuclear warheads over a period of years.

Contrary to the cheery images featured in the collection, life on Ujelang was far from carefree for the refugees, who were not allowed to resettle Enewetak until 1980. The daily hardships were described in great detail when the Enewetakese pressed for compensation before the Marshall Islands Nuclear Claims Tribunal:

Conditions there were characterized by famine, near starvation, and death from illness due to the severe limitations of the environment and resources on Ujelang. There were also polio and measles epidemics, an uncontrollable infestation of rats, and infrequent and irregular field trip ship service.

In its decision, the Tribunal stated that “the conditions suffered by those relocated go far beyond simple annoyance.” In determining the appropriate amount of compensation, the Tribunal adopted an approach based on an annual amount for each person on Ujelang for each of the 33 years between 1947 and 1980. Recognizing that the period of greatest suffering was from 1956 to 1972, the Tribunal awarded an annual per person amount of $4,500 for each of those 16 years. For the remaining 17 years, preceding and following that period, the annual amount is $3,000.

According to a recent United Nations report, however, the U.S. has been less than assiduous about making good on those meager payments.

Tags:atomic testing·Enewetak·law·Micronesia·nuclear weapons·Ujelang