August 8th, 2012

Techno-pessimists have long argued that the democratization of media will not shame elites into better behavior, but will rather make them more cautious about conducting their dirty business behind well-secured doors. The Euthanex AgPro, which is marketed as “the ultimate humane CO2 solution” for the dispatching of pigs, provides one small data point in favor of that viewpoint:

At VAST, we realized that blunt force trauma was not viable in this age of potential Youtube exposure. We also realized that homemade CO2 systems had many problems. We wanted to design a product that was humane, efficient, worker friendly and eliminated negative variables. In short, we would only accept the best possible solution.

As an enthusiastic devourer of swine, I find this a bit disconcerting. Why shouldn’t we be exposed to the brutality of our gustatory choices? I don’t think carnivores will find such visual evidence as off-putting as Big Agriculture fears. It wasn’t all that long ago, after all, that no human could eat meat without having to hack off a chunk of wooly mammoth with their stone blade. I’m not sure why modern businesses think we need to be entirely divorced from that process.

Tags:agriculture·meat·pigs·wooly mammoths

August 6th, 2012

Per the usual, the Olympic boxing tournament has been something of a farce, with scoring scandals predictably aplenty. Every four years, such controversy reminds me of the tale of Bobby Lee Hunter, a once-celebrated boxer I have been trying to locate for the better part of a decade.

Per the usual, the Olympic boxing tournament has been something of a farce, with scoring scandals predictably aplenty. Every four years, such controversy reminds me of the tale of Bobby Lee Hunter, a once-celebrated boxer I have been trying to locate for the better part of a decade.

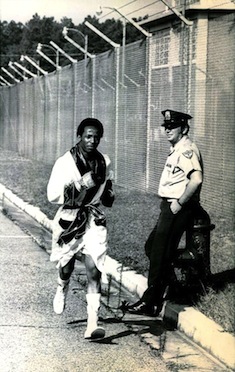

Hunter was a world-beating American flyweight who seemed certain to represent his country at the 1972 Olympics in Munich. This prospect made the powers-that-be quite uncomfortable, for there was something rather unique about Hunter—namely, the fact that he was serving 18 years in a South Carolina prison for manslaughter. Hunter, who trained in the prison yard, was allowed to travel to international competitions with a chaperone, and he was America’s reigning AAU champion when he attended the U.S. Olympic trials in July 1972. The International Olympic Committee shuddered at the thought of Hunter in Germany, with the ever-controversial Avery Brundage openly questioning whether a convict could represent the true Olympic spirit.

A political confrontation was averted, however, when Hunter mysteriously lost to an unheralded fighter named Tim Dement at the Olympic trials. As footage of that bout shows, Dement’s victory was anything but clear cut; the decision could easily have broken for Hunter, and one has to wonder whether the judges felt some pressure to leave the killer at home. (Not to take anything away from Dement, who seems like a cool cat.)

I have long yearned to follow up with Hunter, to see how this experience changed him, for better or for worse. But the trail goes cold in the South Carolina penal system: Hunter was paroled in 1973, but then re-arrested for aggravated assault in 1977. As you might imagine, South Carolina used to keep poor records on the fates of its released convicts, and Hunter’s name is so common that the brute-force approach of cold calling phone numbers isn’t feasible here.

Anyone have a line on what may have become of Bobby Lee Hunter after his boxing career didn’t pan out? Let me know.

Tags:Bobby Lee Hunter·boxing·crime·Olympics·South Carolina

August 3rd, 2012

Granted, I haven’t always been great about keeping up with Microkhan series dedicated to pop culture—both Bad Movie Friday and The Ponchos have fallen by the wayside over the years. But that isn’t going to stop me from launching a whole new series, one dedicated to craven acts of imitation which reveal the cynicism behind much of the entertainment products we consume. I’m gonna call it Knockoffs.

The series’ inaugural subject, NBC’s laughably terrible Supertrain, is a perfect way to kick things off. Like all future Knockoff “honorees,” its concept is obviously copped from an earlier hit—in this case, ABC’s The Love Boat. It takes little imagination to envision the executive meeting at which Supertrain was conceived—men in suits sat around a table and thought, “Okay, let’s do Love Boat, but on some other means of transport. A truck? A dirigible?”

As you might imagine, Supertrain was not long for this world, despite its awesome title-sequence music. After a few weeks of poor ratings, NBC fired much of the production staff, blaming them for failing to give the show a “mystery-adventure” feel. The axed executive producer, Dan Curtis, volleyed back with this nice rejoinder:

You want a light, bright show with mystery and comedy and sophisticated humor and suspense? And you want it once a week? Good luck!

Once the whole Three Mile Island situation went down, there was just no saving Supertrain, which was canceled after just nine episodes. People turned rather sour on the fantasy of having an atomic-powered train roaming the country.

Ideas for Knockoffs? Leave ’em in comments, please. I’m looking for movies, TV shows, books, or other pop-culture artifacts in which imitation was motivated not by a sincere desire to flatter, but rather base cynicism about the profits to be made.

Tags:Knockoffs·nuclear power·Supertrain·Three Mile Island·TV

August 2nd, 2012

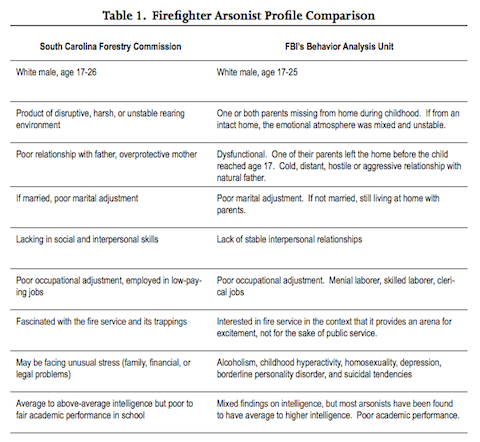

If I so desired, I could probably make this blog all about firefighters-turned-arsonists and still have enough material to post at least once a week. The latest example comes from Opp, Alabama, where a firefighter allegedly set a mobile home ablaze for no discernible reason.

The problem has been serious enough in years past for the Department of Homeland Security to compile a special report, from which the table above (click to enlarge) is drawn. The report’s choicest section deals with motives, and includes this choice quote from an FBI investigator that gets to the heart of why criminals’ rationales so often elude comprehension:

Motives for arson, like other aspects of human behaviors, often defy structured, unbending definition. Strictly speaking, who can argue that vandals are not looking for excitement when they are engaging in their malicious mischief? Add an element of power and revenge and one can see the problem of strict, unyielding classification. Be aware that motivations may change.

That last line is key: Criminals themselves typically don’t totally understand what drives them, and so they will cite different motives over time. This vastly complicates our efforts to understand them—those who disregard society’s conventions have no interest in making our attempts at pop psychology any easier.

This is an irritating truth for writers, of course. How much easier our jobs would be if we could accurately summarize an evildoer’s motives in a single paragraph. And yet how many of us still attempt to do just that, even though such shortcutting does a disservice to our craft.

Tags:arson·crime·firefighting·journalism·psychology·writing

August 1st, 2012

I turned in the second draft of my book yesterday, an event that made me more anxious than glad. I realize now that I only have a few weeks left to sort out some lingering mysteries in the central plot, specifically those related to the main characters’ inner dramas. Without giving too much away, my two protagonists turned their backs on everything they knew, and everyone who loved them. One came to regret that decision, and one did not—though perhaps that is an over-generalization. How did this act of total rejection fit into their attempts to take charge of their own narratives?

I turned in the second draft of my book yesterday, an event that made me more anxious than glad. I realize now that I only have a few weeks left to sort out some lingering mysteries in the central plot, specifically those related to the main characters’ inner dramas. Without giving too much away, my two protagonists turned their backs on everything they knew, and everyone who loved them. One came to regret that decision, and one did not—though perhaps that is an over-generalization. How did this act of total rejection fit into their attempts to take charge of their own narratives?

One masterpiece I’ve been looking to for inspiration is “The Making of a Terrorist,” a five-part United Press International series from 1970. (Link here; scroll down to the bottom for the stories.) The series, which earned a Pultizer Prize, recounts the short but fascinating life of Diana Oughton, the daughter of a wealthy Chicago family who died while building bombs for the Weathermen. It is an epic piece of reporting, rich in detail about Oughton’s transformation from privileged young lady to violent radical. This passage, in particular, is something I’ve been reading again and again; it describes a key moment from the two years that Oughton spent in Guatemala, working for Quaker-run volunteer program:

Diana’s growing concern over the American influence in Guatemala was matched by a growing dislike for the American tourists who came to Chichicastenango and stayed at the Mayan Inn, where the spent enough in a week to support an entire Indian family for a year. She hated the Americans’ gaudy clothes, their broken Spanish, their silly questions, the way they snapped pictures of the Indians. She began to hate doing the marketing because the Americans would always spot her blonde head above the crowd and ask what in the world an American girl was doing in such a godforsaken spot.

Diana’s distaste for American extravagance was also directed at her friends. When an old college friend and her husband, both heirs to large fortunes, came to Guatemala for a visit, Diana was disgusted by their complaints about the food and water and by their extravagant spending. “My God,” Diana said to Kimmel after the couple had left, “She used to be my very best friend in the whole wide world.”

That moment resonates with me because it’s something we’ve all experienced to some degree: the realization that the people with whom we shared childish pleasures have become strangers to us. But for Oughton, it represented something even deeper: that when she did return to the U.S., she would never be able to melt back into her previous life. The comfortable yet boring future that had been laid out for her during her years at Bryn Mawr was now odious. She had to find a way let the world know she rejected it in the strongest terms possible.

Tags:Diana Oughton·journalism·terrorism·Weathermen

July 31st, 2012

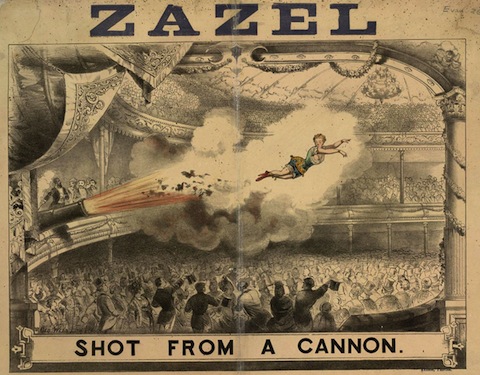

The human cannonball act is one of the most notoriously dangerous in all of circus-dom; performers have little to no control over their movement, so any minute error in firing trajectory is certain to cause catastrophe. The legendary Zazel, née Rossa Matilda Richter, was thus fortunate to survive her 19th-century career, though she did break her back while working for P.T. Barnum. Per this source, however, Zazel could have easily satisfied the English masses by simply removing a few articles of clothing, rather than risking life and limb:

Much of Zazel’s appeal lay in the fact that, in order to fit into the cannon, she had to she most of her Victorian clothing.

How many human cannonballs had to perish because of England’s sexual repression?

A wonderful gallery of Zazel photos here. And more biographical details here; kudos to her for her early advocacy of firefighter nets.

Tags:daredevils·England·human cannonballs·sex·Victorian·Zazel

July 30th, 2012

Endeavoring mightily to complete the second draft of the book by day’s end. Revel in the awesome that is Pearl Chang, and catch you back here tomorrow morning.

Tags:martial arts·movies·Pearl Chang·Taiwan

July 26th, 2012

Compared to the Games of the late Cold War, when steroids were integral to athletic success, this year’s Olympics will be remarkably clean. Yet we also know that drug use has not vanished—how could it, give the rewards at stake at the ultra-competitive nature of those tempted to use? The big question is what percentage of cheats are ensnared by the current testing regime.

A definitive answer is impossible, of course, but a little light was shed by an email I recently received from an elite track-and-field athlete—not an Olympian, but someone who competes at the very highest levels of their sport. I promised to protect this person’s identity, for what they had to say was fairly damning, if somewhat hyperbolic:

In the past 8 months, I have been tested outside of competition six times by the USADA. I can only imagine how often USA Track & Field’s top stars are tested. In most countries (e.g. Belarus, Jamaica) they don’t even have a real agency like USADA to conduct Out of Competition tests. Sure, when an athlete wins an event at the Olympics, they get drug tested, but that doesn’t mean the person didn’t use steroids the entire year beforehand and simply stop using them in time for the drugs to clear his/her body at the Olympics. The science, which can be easily ascertained by a chemist or doctor is such that an athlete could still be retaining all of the physical advantages of the drugs without the metabolites appearing in their urine. The fact that most athletes around the world have less than a 0.1% chance of getting tested outside of the Olympics or World Championships is not a deterrent at all. Very few countries have the robust out-of-competition testing regimen that the United States has.

Something needs to be done outside of the Games themselves to ensure a level and fair playing field. If the IOC truly cared about this issue, they would mandate that an athlete have a certain number of random, out of competition tests with a year, six months, and three months from the Olympics.

Digging a bit deeper into the statistics for track-and-field athletes, it seems that my correspondent’s 0.1 percent figure was a bit low. But when I pinged him back with a correction, he made an important observation about the ease with which tests can be skipped:

I know that in the US, if you miss more than three out-of-competition tests during an 18-month period that it is the same as a positive test and you receive a suspension. I know many athletes in other countries go to “training camps” in places like South Africa for weeks or months at a time during the off-season and may not report their whereabouts to avoid testing officials.

The upshot is that elite athletes in many countries have the odds in their favor should they elect to enhance their performance with drugs. The penalties for getting caught are extreme—one could lose everything, as lengthy bans are the norm. But if you’re smart about your intake and your national sports authority doesn’t give a damn about testing, you may only face a one in ten chance of detection. After dedicating your whole life to an arcane pursuit, and knowing that drugs could provide just the boost you need to achieve athletic immortality, who wouldn’t take that risk?

Tags:drugs·Olympics·sports·steroids

July 25th, 2012

I’m one of those blokes who will argue ’til the end of time that The Godfather: Part II far surpasses the original. That’s largely because of the whole Vito Corelone backstory, which includes the single greatest flawed gangster of all time. But I also dig the quiet tension created by Michael Corleone’s vacillation over his family’s future. The angel on his shoulder tells him to make good on his promise to his wife and take the whole enterprise legit; the devil, of course, whispers very different instructions in his ear.

In the late 1960s, Chicago’s Conservative Vice Lords faced a similar choice. The gang ultimately opted to join the legitimate economy by opening a series of businesses on the city’s depressed West Side. They did so with seed money obtained from a number of charitable foundations, including the Rockefeller Foundation, which saw the CVLs’ transition to enterprise as a key step in Chicago’s renewal.

But within a few years, all of the CVLs’ stores had closed and they were back to working in the shadows, to Chicago’s great detriment. This fascinating post-mortem offers up a bevy of explanations for the CVLs’ failure, most of which can be distilled into a single adage: Street skills don’t necessarily translate into boardroom skills. This lesson, in particular, is something that Michael Corleone knew all-too-well:

While Vice Lord leadership were using these [businesses] to remake themselves into a bona fide community and political powerhouse, many of the thousands of rank-and-file Lords members, who were still facing conditions of poverty and blight (CVL, Inc., leaders took yearly salaries between $10,000 – $15,000), continued to act as violent criminals. Traditionally, leadership of a street gang goes to the biggest, strongest, and most violent members, and these leaders must constantly be on guard against newer, younger members, who attempt to prove themselves even more violent than their leaders. This is how the Vice Lords had always operated, and now Perry, Alford, Gore, and others, who by the late 1960s were in their late 20s, faced thousands of power-hungry teenagers bent on rising in the gang hierarchy, especially a subgroup of young Vice Lords calling themselves the Black Aces. Thus, violence was difficult to avoid.

It’s not clear from the write-up whether the CVLs’ leadership ever considered taking on young rivals as salaried employees, which might have been wise. Enemies closer than friends and all that.

Many more Conservative Vice Lords artifacts here. I love their letterhead.

Tags:Chicago·Conservative Vice Lords·crime·economics·movies·The Godfather II

July 24th, 2012

A day late on this month’s deadline for my Wired column, so you’ll have to wait twenty-four hours for my cogent thoughts on either human cannonballs or gang entrepreneurship. (Sorry, haven’t decided yet.) In the meantime, occupy your spare moments by delving into this salacious collection of trial pamphlets, which provided true-crime buffs with plenty of reading material in the era before yellow journalism. The illustrations of the cases involving “criminal conversation” with married women (see above) are particularly delightful.

Tags:crime·law·trial pamphlets

July 23rd, 2012

Nineteen days ago, a Swedish advertising agency made waves by airdropping a thousand teddy bears over Belarus—a minor protest against the nation’s repression of free speech. A student in Minsk posted several photos of the bears on his site, and was subsequently arrested by Belarusian authorities for undisclosed reasons. That arrest caused the Swede behind the stunt to release this rather awesome open letter to President Alexander Lukashenko, which I sincerely hope will pop to everyone’s mind whenever they hear the name of Belarusian dictator:

Recently, you announced that you, personally, guaranteed the effectiveness of the Belarus defence. You have spent 20 billions of euros on an air defence system that could not detect a homebuilt aeroplane with a cargo of teddy bears. As Pavel Kozlovsky, former Belarus minister of defence, expressed: You lead a regime that puts all its energy into pretending that the patient is healthy, but none into curing her.

Reports in Russian media – which you dare not censor – have caused many people to laugh at you. On the internet, you are described as a clown. But we are not naive. You are something much more frightening – an armed clown. Though in the long run, not even a heavily armed clown can stop people from laughing. And when people laugh at you, not even your friends will want to stick around.

A ground’s-eye view of the airdrop can be seen here. I guarantee you that someone fetched that bear that got caught in the tree; fingers crossed that they were not arrested for doing so.

Tags:advertising·Belrus·dictatorship·Sweden·teddy bears

July 19th, 2012

There are few more colorful characters in recent modern Cleveland history than Alphonso Woodall, a daredevil who performed as “The Human Kite.” A former Army Air Force mechanic, Woodall built his own rig so he could soar above Lake Erie with water skis strapped to his feet. His derring-do eventually attracted the interest of a B-grade reality show called You Asked for It, which agreed to pay Woodall $500 for his act—though over dry land, attached to a car instead of a boat.

The stunt did not go well, to say the least, and Woodall sued the show’s producers. He was awarded $70,000, which the producers then appealed. The resulting decision established what is the most important precedent in the arcane field of daredevil law, one that establishes that the men and women who risk their lives for our entertainment are not entirely to blame when things go awry. For even the simplest stunt involves the expert participation of support staff—aid that was sorely lacking in Woodall’s case:

Soon after his arrival in Los Angeles on March 22, 1959, one Hochman drove plaintiff from his hotel to the drag strip where the stunt was to be put on. Hochman said he was to be plaintiff’s driver but when plaintiff discovered he had been driving with his emergency brake partially on he refused to have Hochman. So Welo was assigned by defendant to drive in the exhibition flight. Plaintiff gave Welo explicit and repeated instructions as to speed, signals, etc., and Welo was told to slow the car after reaching a speed of 27-30 miles; he agreed to do so. Plaintiff’s last word to Welo before the flight was, “Remember, now, don’t go over 30 miles an hour,” to which Welo agreed. Welo himself testified by deposition: “I have never represented myself to Mr. Woodall or anybody else as being a driver because I am not.” In fact Welo never held himself out to Henderson as a stunt driver, had never been used as such by defendant, but had been assigned to this stunt notwithstanding the assurances previously given to plaintiff.

On the occasion in question, according to plaintiff, Welo started too slowly, was given a signal to go faster and was supposed to accelerate at once; the kite jumped along and did not take off; then Welo gave a quick surge forward and the kite rocketed up. Plaintiff started giving the wave- off signal (for an emergency stop); the kite reversed itself, but plaintiff still felt a forward motion, the kite began to fall and he could no longer control it. They were jerked along the ground and plaintiff could feel the rope taut and could feel the forward motion. His estimate was that the car got up to 45 miles.

The kite turned over on plaintiff and he was seriously injured. He began to yell, “Too fast, too fast, I told him too fast.” A boy who was about five feet from plaintiff when on the ground heard him, less than a minute after the accident, repeating, “I told him not to go too fast.”

There is a halfway happy ending to this tale, at least for Woodall: Though still hampered by his broken leg in early 1960, he rescued a duck hunter whose boat had capsized on Lake Erie. For this he was awarded a Carnegie Medal for heroism—though, unfortunately, the accompanying $500 cash prize caused him some financial problems down the line.

View more photos of the Curt Flood of daredevil-dom here. Yes, he had an odd grudge against Martin Luther King Jr.—chalk it up to the madness of geniuses.

(Image via The Cleveland Memory Project)

Tags:Alponso Woodall·Cleveland·daredevils·law·The Human Kite

July 18th, 2012

Not sure how many Italian speakers I have in the Microkhan fold, but I felt the need to give some love to this new edition of Now the Hell Will Start from Milan-based Edizioni Piemme. I was tasked with approving the text, a job that gave me a new appreciation for the art of translation. I don’t speak a word of Italian beyond the standard food-related stuff, so I spent a good deal of time slotting phrases into Google Translate. And again and again, I was struck by how gorgeously the translator managed to transpose sentences into her native tongue. There is no greater example, perhaps, than the book’s very first line, which in English reads like this:

Not sure how many Italian speakers I have in the Microkhan fold, but I felt the need to give some love to this new edition of Now the Hell Will Start from Milan-based Edizioni Piemme. I was tasked with approving the text, a job that gave me a new appreciation for the art of translation. I don’t speak a word of Italian beyond the standard food-related stuff, so I spent a good deal of time slotting phrases into Google Translate. And again and again, I was struck by how gorgeously the translator managed to transpose sentences into her native tongue. There is no greater example, perhaps, than the book’s very first line, which in English reads like this:

It is best to use discretion when confronting an emotionally shattered man, especially if he’s holding a semiautomatic rifle.

The Italian version, by contrast, starts things off in much more elegant fashion, by creating a repetition that ratchets up the tension:

Bisogna usare molta cautela. Quando si affronta un uomo sconvolta, soprattutto se imbraccia un fucile semiautomatico, bisogna usare molta cautela.

(One must be very cautious. When facing a distraught man, especially if he is wielding a semi-automatic rifle, one must be very cautious.)

I also love the fact that they reworked the title as Vivo o Morto, which sounds like one of Sergio Leone’s unproduced screenplays. Plus it gives me something to discuss with Tom Clancy should we ever meet at a cocktail party.

Tags:books·Italy·Now the Hell Will Start·Tom Clancy·translation·Vivo o Morto

July 17th, 2012

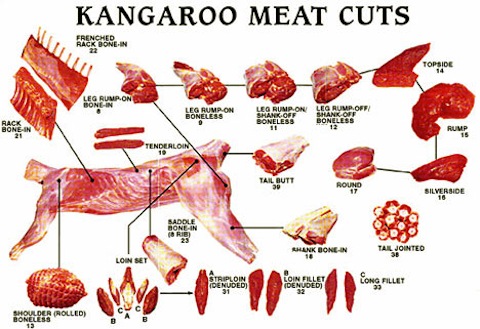

The Jenga-like nature of markets is revealed in the tale of Australia’s kangaroo-meat crisis. There was a time when steaks and chops taken from Down Under’s most celebrated marsupials seemed destined to become a staple of butcher’s shops the world over. No country developed a more ravenous appetite for kangaroo meat than Russia, which came to account for 70 percent of the global market. Then, in 2009, Russia abruptly decided that it wasn’t cool with the hardscrabble ways in which the meat is produced. (See here for the first-person account of an Outback ‘roo shooter.) The Russian ban has yet to be lifted, to the great distress of Australian producers who claim they’re on the edge of extinction.

So what is the solution, other than coaxing Russia to start eating ‘roo meat once more? Sausages:

Tapping new markets for roo meat is seen as the best solution to help the struggling industry and deal with the overpopulation of kangaroos.

John Kelly, Australian Kangaroo Industry Association chief says top quality cuts of kangaroo meat – like steaks – continue to be exported to over 50 countries.

Mr Kelly says the problem is selling what is termed manufacturing meat – like sausage mince – from kangaroos.

“What we desperately need is for these other meat cuts to find a new market, as this is what the Russians were buying,” he said.

This presents a fascinating marketing challenge: How do you convince consumers to not only start eating a meat that is strange to them, but also one that is so low-grade that it must be mashed up into a tubular concoction rife with herbs and spices? And how do you compete on price against industrial meats like beef and pork? Roaming around the Outback with a rifle is labor intensive, and thus expensive.

Leave your ideas for kangaroo-sausage ad slogans in comments.

Tags:agriculture·Australia·economics·hunting·kangaroos·marketing·Russia

July 13th, 2012

Like many a non-fiction nerd whose tastes run toward the sinister, I was enraptured by Richard Lloyd Parry’s People Who Eat Darkness. The book’s central narrative was compelling enough—a young British woman’s disappearance set against the backdrop of Japan’s hostess-club industry. But what really makes the work sing is Parry’s exploration of media drama, and how so much of it is based on unspoken codes of conduct. Just like Roppongi hostesses and their salarymen clients, who instinctively know which sexual lines can never be crossed, reporters and distraught subjects are expected to fill pre-determined roles on the public stage. And as People Who Eat Darkness makes clear, we detest those who refuse to play along:

In Britain, just as in Japan, powerful conventions govern the way that people under the load of unbearable stress are expected to behave in public. We like our anguished victims to be passive, confused, and broken; where those characteristics are absent, suspicion flourishes…

A Japanese family, deprived of their daughter in sinister circumstances, would shuffle before te cameras with downcast eyes. Their words would be halting and few. They would express love for their child, anxiety for her safety, and appeal to the good nature of her abductors to give her back. There would be tears, and even apology, or something close to it, for “causing inconvenience” by their plight…

In Britain, there is a little more room for the expression of individual anger and resentment, but only within limits. An unspoken code governs people in these situations, as strict in its was as old formalities of mourning.

Parry then describes the first press conference held by the father and sister of the abducted girl:

The photographers were crouching, lurking at the bottom of the podium, their lenses angled upwards. They were waiting for the shot that would make the following day’s papers: a finger brushing away a tear, a face crumpled with anxiety and despondency, even just the clenched hands of father and daughter. But there was nothing of the kind.

The press and public did not like this refusal to obey convention one bit. They found it unsettling, argues Parry, for it stripped us of our chance to feel the catharsis we so desperately crave. By refusing to break down on the podium, these family members took away our theater. And so we punished them by treating them as partly responsible for young Lucie Blackman’s bitter fate.

Read the whole book for more; it also includes a great thread about the marginalized culture of Koreans in Japan, and how the burden of “otherness” might have affected the development of the tale’s villain (pictured above).

Oh, and Parry is also the writer behind one of my all-time favorite Granta stories, “What Young Men Do.”

Tags:books·crime·Japan·People Who Eat Darkness·psychology·Richard Lloyd Parry

July 12th, 2012

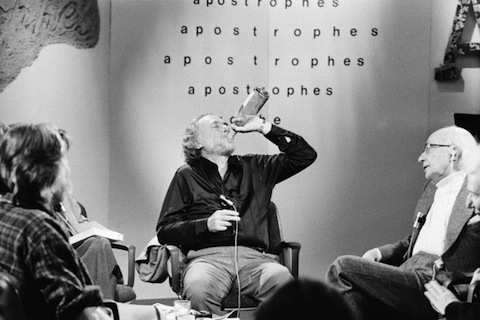

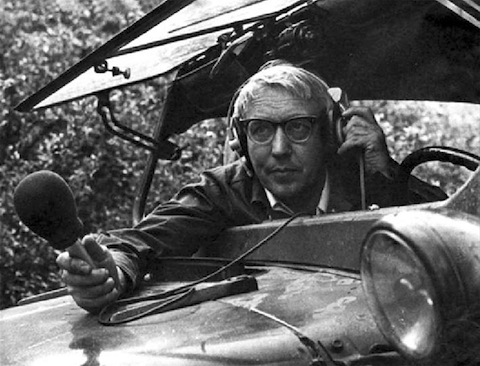

The above photo of Charles Bukowski on French TV, snapped by the Sophie Bassouls, is everything that we’ve come to expect of the so-called “laureate of American lowlife.” Yet for me, the image does not call to mind a scene from one of Bukowski’s stories or poems, but rather the wisdom of a less-noted public intellectual: Ozzy Osbourne. For it is Ozzy who, in his VHI “Behind the Music” episode, best summarized the feedback loop that keeps otherwise intelligent celebrities on the path to self-destruction:

If you went to your job in an evening dress with a Nazi hat on, drunk as a skunk, they’d say, “What are you doing, man?” But if I turn up [like that], they go, “Ah, should be a good night tonight, Ozzy’s up it tonight!”

This is the line I always think of when another talented artist falls into an early grave due to drugs or drink. How can we be terribly surprised when we offer them our warmest adulation for being their most bonkers?

(Image via Everyday I Show)

Tags:addiction·alcohol·celebrity·Charles Bukowski·Ozzy Osbourne

July 11th, 2012

Sorry for the radio silence today. Working on the publicity questionnaire for my long-discussed next book, which means the light at the end of the tunnel is getting a notch brighter. Back tomorrow with deep, deep thoughts on self-destructive celebrities.

Tags:music·Nigeria·The Lijadu Sisters

July 10th, 2012

Turkmenistan’s National Space Agency has a new chairman, who will be expected to oversee the monumental task of launching the country’s first satellite. I’m still not entirely clear on why Turkmen dictator Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov is making this such a huge priority, for the official explanation is gobbledygook: the satellite, the nation’s state news agency tells us, will be “designed to promote the development of space technology and modern telecommunications systems and the creation of regional innovation zones.” But suffice to say that the new space tsar, Alladurdy Atayev, will be under intense pressure to get the job done, regardless of its usefulness.

If Vegas was taking bets on whether Atayev will still have his job on launch day, however, I would bet a fortune on the negative. As evidenced by his recent handling of Turkmenistan’s bread crisis, President Berdimuhamedov is not a patient man:

In response to price rises and diminished harvest, Berdymukhamedov has fired Agriculture Minister Merdan Bairamov and Association for Bread Products Chairman Yeldash Ashyrov, the State News Agency of Turkmenistan reported on July 6.

A loaf of traditional white state-baked bread that formerly cost 1 TMT (35 US cents) now sells for 1.6 TMT (58 US cents). Privately baked bread and other baked goods also went up in price 30%.

Never mind that such price fluctuations are probably attributable to such uncontrollable factors as climate, demand, and transportation costs. Like most dictators who surround themselves with obsequious dolts, Berdymukhamedov seems incapable of grasping complexity. Which makes me think he will be none-too-pleased when he inevitably hears that his precious satellite might be slightly harder to launch and operate than his private jet.

Tags:agriculture·dictatorship·economics·space·Turkmenistan

July 9th, 2012

The French photographer Marc Garanger, best known for his 1960 series on Algerian women, began his career while serving in the army. He was assigned to Algiers in 1960, right as France was beginning to accept that the jewel of its North African empire was fated to achieve independence. The inevitably of this outcome caused Garanger’s superiors no shortage of bile; one bitter commander, in particular, accidentally motivated Garanger to commit himself to making art that vibrated with empathy:

When the army forced villagers to abandon their homes and to build new ones around the French army’s barracks, Garanger’s commander asked the photographer to catalog all villagers to produce mandatory ID cards. “In 10 days I took 2000 images,” Garanger tells BJP. “The first days the portraits I took showed the women with their veils on. When I showed the image to the commander, he asked for the veils to be removed.” It was, for the photographer, yet another colonising move from the French army, echoing, he says, Edward Curtis’ images of Native Americans. “I felt it was a similar story. Curtis took images of a people being massacred by another. I wanted to show the violence of this war, not physical violence, but the violence imposed on these women.”

Upon seeing the final images, Garanger’s captain suddenly stood up screaming: “Come see, come see how ugly they are. They look like monkeys.” Upon hearing this, Garanger swore he would spend the rest of his life proving his captain wrong.

More from Garanger’s Algerian series here. It’s a collection I’ve been looking at a lot as I plow through the second draft of my next book.

Tags:Algeria·France·Marc Garanger·photography

July 5th, 2012

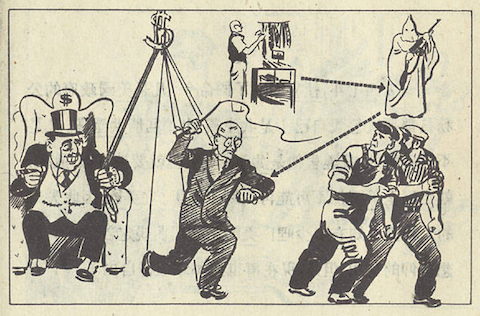

Quite some time ago, I posted about classic Soviet animation that hilariously stereotyped America as a Darwinian nightmare. As someone who grew up thinking that life in Moscow was accurately portrayed by that Wendy’s fashion show commercial, I was strangely pleased to learn that my Soviet peers were similarly duped into thinking that human happiness was utterly absent on the Cold War’s opposing side.

But the Soviets were not the only ones to produce hyperbolic visions of American dysfunction during the last century. This Chinese propaganda pamphlet, part of a stellar collection of such materials, makes the ostensible Leader of the Free World seem like the vilest dystopia ever. The images are ludicrously over-the-top, though not without a microscopic grain of truth on occasion. A few more favorites after the jump. [Read more →]

Tags:China·Cold War·comics·Communism·propaganda

July 3rd, 2012

There is a common and compelling narrative regarding the power of immigrant remittances: A busboy or chambermaid supports their entire native village by wiring money back home. We love these stories because they affirm the economic superiority of our circumstances, as well as the continued robustness of the American dream—through gumption and hard work, anyone can earn a relative fortune on these shores.

Yet as is always the case, the reality of the situation bears only a passing resemblance to the likable myth. Immigrants often chafe at the demands placed upon them by their relatives back home; they find it difficult to provide as much money as requested, and the resulting feuds can lead to the fracture of familial bonds. This excellent study (PDF) of Somali immigrants in Southern Maine drives that point home, particularly in this account of a young woman’s burden:

According to Somalis in Lewiston, one of the reasons that pressure on those living in the diaspora to send money to their relatives is so great is because people living in and around Somalia do not understand how difficult it is to earn a decent living in the West. Kaltun, whose mother and close relatives live in Ethiopia’s Somali region, says that she tries to send as much money as she can as often as she can. She recalls, “I once sent my mother $300 and she refused to take it, saying it was too little. I could live on that much money! It is more than 2500 birr [in Ethiopian currency], and a Doctor’s salary is 500 birr… [But] she has twelve people living with her (four children of her brother who died and seven grandchildren and one other [child of one of her siblings]. I am the only child who is outside, so she depends on me, but she thinks that I have more money than I really do. I want to bring her here to show her how we live. She won’t want to stay. But at least she will see how difficult it is for me. I worry so much, I have so much stress about being able to earn enough money that I have gained a lot of weight. If I went back I would lose it I am sure.”

It will be interesting to see whether that sort of stress convinces some Somalis to return home, as this group is now urging members of the nation’s diaspora. Things do seem to be looking up in Mogadishu, after all. Whichever returnee from Maine establishes the first lobster shack at Lido Beach could make a fortune.

(Image via Bates Magazine)

Tags:economics·immigration·Maine·remittances·Somalia

July 2nd, 2012

Thanks a million for your patience while I was up in Maine, hacking away at the book and knocking back a whole mess of these. Catching up on a zillion different things today, then back tomorrow with a post about Somali immigrant remittances.

Tags:beer·Cold War·Maine·propaganda

June 29th, 2012

A quick backgrounder on a man whose intense dedication to an arcane pursuit I truly admire, though I can by no means claim to understand it:

A cryogenics and nerve cells specialist, Russian biophysicist Boris Nikolayevich Veprintsev (1928-1990) started recording Soviet birds on homemade equipment in 1957 while studying at Moscow University, undertaking annual birding expeditions throughout the country, a habit he kept almost until his death. Veprintsev collected thousand recordings documenting the Soviet avifauna as well as mammals, fishes, amphibians and insects of the East European Plain region, including rare and now extinct species. His first LP, Morning in the Forest, was published in 1960, with the approval of Khrushchev himself, though Veprintsev’s family had been harassed by the Soviet regime, and Boris’ father sent to the gulag in the 1940s. Veprintsev subsequently published as many as 28 LPs, amounting to over 500 bird voices. He founded the Soviet Archive of Wildlife Sounds of the USSR Academy of Sciences in 1973, located in Puschino-on-Oka, 120 km south of Moscow, where Veprintsev worked as head of the Academy’s Laboratory of Biophysics of nerve cells from 1966.

Much more here, though you’ll probably have to use Google’s handy translate function.

(Image via Continuo)

Tags:birds·music·Soviet Union

June 27th, 2012

There was a time when Vanna White aspired to be more than just another game-show letter turner. Like all television personalities, she longed to cross over into the world of film, so that someday her name would be mentioned in the same breath as Hollywood’s great. Unfortunately for White, her acting chops leave something to be desired, as evidenced by 1988’s Goddess of Love (above). I’d like the think the project flopped in part as karmic retribution for White’s obvious arrogance, which comes across vividly in this 1987 profile:

She sums up her current status by licking a finger, then applying it to one of her tan-and-shapely legs while making a hissing sound to indicate sizzling heat.

The Mario Balotelli of game-show hostesses, for sure.

Tags:Goddess of Love·Mario Balotelli·movies·television·Vanna White

June 25th, 2012

By the time you read these words, I’m gonna be in on an island off the coast of Maine, hunkering down to revamp the book and spend some last moments with the royal trio before it becomes a quartet. Just a sporadic few things this week—back to solid land on July 2nd.

Tags:Asha Bhosle·Bollywood·music

June 22nd, 2012

This weekend’s national election in Papua New Guinea is a real grudge match between bitter enemies: Sir Michael Somare, the dominant figure in the nation’s politics since independence, and Peter O’Neill, the man who replaced him as prime minister under dubious circumstances. The nastiness of this rivalry is reflected in the cost of electoral corruption, which seems to have skyrocketed this cycle:

In a nation where cash handouts at election time are widespread, observers say the cost for first-preference votes has increased by as much as 30-fold.

“In some areas the going rate for a first-preference vote is 1000 kina (approximately $A500), and other areas in the highlands it’s as much as 3000 kina for a first-preference vote,” said Nicole Hayley, leader of the Domestic Election Observers group.

In the 2007 election, first-preference votes were being bought for 100 kina.

I wish there was some way to chart the rise and fall of these prices in real-time, so we could get a sense of how they respond to events like the release of early results or other political scuttlebutt. A canny citizen might want to hold off voting until the last possible moment, in the hopes that the campaigns will up their offers.

My prediction, by the way, is that O’Neill will emerge victorious amid accusations of rampant fraud. And Papua New Guinea’s toxic political climate will continue.

(Image via The Garamut, which you should follow for PNG election coverage)

Tags:corruption·economics·elections·Papua New Guinea

June 21st, 2012

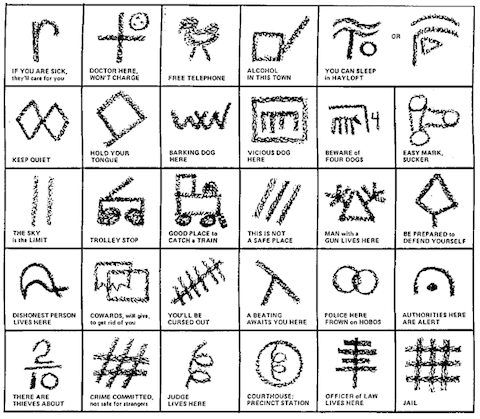

The great industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss is the man most responsible for preserving the art of hobo signs, which he chronicled in his 1972 masterwork Symbol Sourcebook. A good three decades after the end of the Great Depression, Dreyfuss tracked down the backstories for 60 of these signs, which hobos used to tip off their fellow vagabonds. What is most fascinating about these pictograms is that they were universally understood by a population that had no way to act in concert. As the brilliantly named hobo-ologist Jules J. Wanderer noted in his 2001 paper “Embodiments of bilateral asymmetry and danger in hobo signs,” one way these signs worked was by tapping into the American brain’s natural bias for right over left:

For example, paths, roads, or trails were not marked with words indicating they were ‘preferred directions’ to travel or places to be ‘avoided.’ Instead objects were marked with hobo signs that discursively differentiate paths and roads by representing them in terms of bilateral asymmetry, with right-handed directions, as convention dictates, preferred over those to the left.

Note that I said “American brain.” I wonder if Japanese hobos would have come up with signs that oriented in the opposite direction, based on how their written language is arranged.

(h/t Jordan for passing along Wanderer’s paper)

Tags:hobo signs·hobos·language·neuroscience·psychology

June 20th, 2012

When Nigerian soccer star Christian Obodo was briefly kidnapped earlier this month, I was struck not only by the boldness of the crime, but also by the crooks’ obvious sensitivity to economic realities. For as this early account of the caper makes clear, the kidnappers and Obodo’s family started the negotiations on more-or-less the same page:

Obodo’s brother, Kenneth Obodo, who is also a footballer in Italy and is currently in Nigeria, was quoted by Italian news agency ANSA as saying: “Christian is fine. We are in touch with the kidnappers, who want some money.

“We can’t give them more than 100,000 euros ($125,000). Unfortunately these things happen in our country.”

His brother-in-law, Obidike Okechukwu, was quoted by ANSA as saying that the kidnappers had asked for a ransom of 150,000 euros.

In other words, the initial ransom demand and the family’s upper limit were just 50,000 euros apart. Which makes me wonder: Is there a basic formula that kidnappers can employ to determine tolerable ransoms? Is it a certain percentage of a victim’s net worth or annual income? And did they do research on Obodo’s salary with Udinese, his club in Italy’s Serie A, to figure out a ballpark figure to charge his relatives?

The average salary of a Serie A player is 5 million euros, though Obodo, who was on loan to Lecce this past season, certainly makes far less. Safe to say that the kidnappers quoted a opening ransom equivalent to 15-20 percent of annual gross income, with an toward settling for 10 percent? Sports agents typically take 15 percent, after all, so perhaps kidnappers feel that is a good place to start—a cut that is neither insignificant nor back-breaking.

If only all negotiations could open with such little disparity between the conflicting parties: In today’s dispute over Port Moresby’s entire water supply, the sides’ proposed “ransoms” are off by approximately $140 million. That should be a fun negotiation.

Tags:Christian Obodo·economics·kidnapping·Papua New Guinea·soccer·sports

June 18th, 2012

I resisted the urge to write about the 1992 Los Angeles Riots during their anniversary earlier this spring, because I feared that anything I produced would smack of extreme navel-gazing. But I do feel compelled to mark the untimely passing of Rodney King, for there’s no doubt that his ordeal and the drama it produced was one of the cornerstone experiences of my Angeleno adolescence. I was a high-school student when the city exploded on April 29, 1992—I first heard about the violence from a baseball teammate, who boarded our bus after a tough loss and yelled, “The city’s on fire!” None of us believed him; it wasn’t until I got back home and heard an obviously shaken KLOS DJ appeal for peace that I realized something truly dreadful was happening.

The riots opened my eyes to the fact that Los Angeles was a far more complex place than my teenage brain had ever imagined. And that revelation led to some choices that ultimately made me a more curious and empathetic person—skills that have served me well in my chosen vocation.

I remember watching King’s speech above on our living-room TV. To this day, I don’t know how he maintained the composure necessary to speak with such clarity and eloquence. It was a single momentous achievement in a life that was otherwise marred by demons and disappointments. But it is a finer legacy than most men will ever leave behind.

Tags:Los Angeles·riots·Rodney King

June 15th, 2012

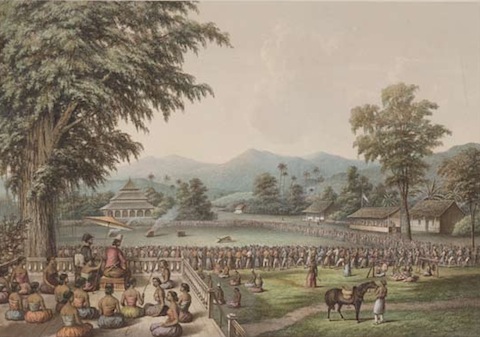

Rampok macans were Javanese ceremonies which centered upon the slaying of tigers, perhaps as a symbolic way for humans to confirm their dominance over nature. The tigers were not sacrificed, per se, but rather forced into combat that virtually guaranteed their deaths—either against spear-wielding humans or, far more spectacularly, water buffalos. An eyewitness described the tiger-versus-buffalo fights like so:

The first encounter is usually tremendous; the buffalo is the assailant, and his attempt is to crush his antagonist to death against the strong walls of the cage, in which he frequently succeeds. The tiger, soon convinced of the supreme strength of his antagonist, endeavours to avoid him, and when he cannot do so, springs insidiously upon his head and neck. In the first combat of this nature to which I was witness, the buffalo, at the first effort, broke his antagonist’s ribs against the cage, and he dropped down dead. The buffalo is not always so fortunate. I have seen a powerful tiger hold him down, thrown upon his knees for many seconds; and in a few instances, he is so torn with wounds that he must be withdrawn and a fresh one introduced. In nineteen cases out of twenty, however, the buffalo is the victor. After the first onset, there is little satisfaction in the combat; for the animals, having experienced each other’s strength and ferocity, are reluctant to engage, and the practices used to goad them to a renewal are abominable. The tiger is roused by fire brands and boiling water and the buffalo, by pouring upon his hide a potent infusion of capsicums, and by the application of a most poisonous nettle (kamadu) a single touch of which would throw the strongest human frame into a fever.

I am saddened by the fact that the human observers could not be satisfied by the animal combatants’ obvious respect for one another’s skills. The tiger and buffalo’s reluctance to rengage would seem to signal something truly wondrous about nature—namely, the capacity for creatures to learn from past experiences, and to exist more harmoniously as a result. That heartening truth seems to have been lost on the rampok macan attendees, alas.

(Image via KITLV Collections)

Tags:buffalos·Indonesia·Java·rampok macan·religion·tigers